By Russel Webster

Prison staff say illicit phones are about organised drug dealing while prisoners view them more as tools to keep in touch with family.

HMPPS research paints complex picture

I highly recommend reading a piece of recent (19 July 2018) research by HMPPS into the demand for and use of illicit phones in prison.

The authors, Anna Ellison, Martin Coates, Sarah Pike, Wendy Smith-Yau & Robin Moore, explore the use of smuggled mobile phones in prison in considerable detail, contrasting the views of prison staff and prisoners themselves on why and how prisoners increasingly use mobiles inside.

The researchers examined three key questions:

- What drives the demand for mobile phones within prisons – how much is for maintaining family contact and how much is for other more criminal purposes (including criminal networks, gangs, terrorism)?

- Are certain types of prisoners more likely to want a mobile phone and so drive demand in particular establishments?

- Which non-technical factors could be most effective (and cost effective) in reducing both the supply and demand for mobile phones in prison (including ways of counteracting the prison economy that surrounds the use of mobile phones)?

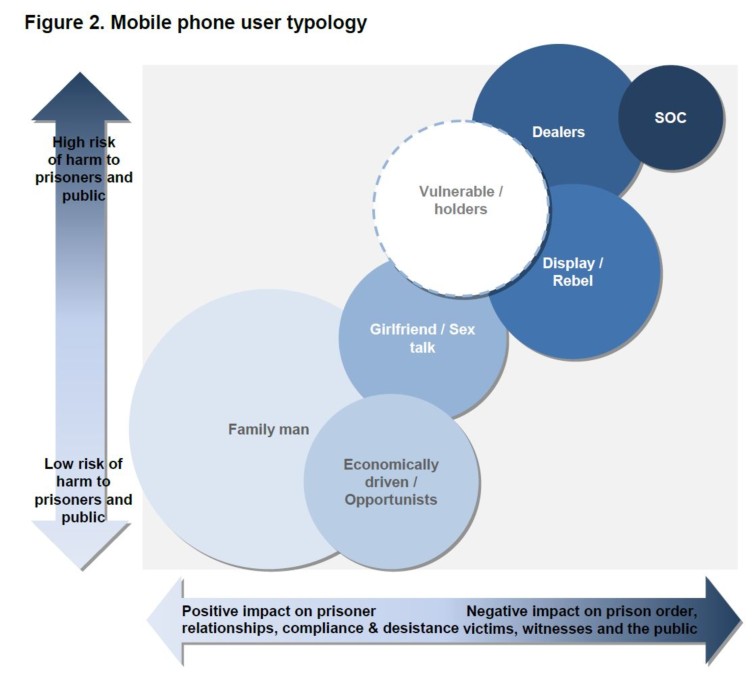

- This short blog post only highlights the main findings, but the qualitative research is fascinating and gave rise, amongst other things, to the typology of prison mobile phone users reproduced below.

The scale and type of mobile phone use

Heads of Security reported that mobile phones had become a feature of prison life across the estate, with the exception of women’s prisons and those housing juveniles. Mobile phones were seen by both the security function and prisoners as a major component of the illicit prison economy, with mobile phones acting as a key facilitator of drug dealing and use within establishments.

A range and variety of phones were being used within establishments, with the smaller, easier-to-conceal phones being the most sought after models. Smart phones with greater functionality were seen by prisoners as posing greater risk of detection and confiscation, and so were less popular. Prices of such phones had been falling as a result.

Why do prisoners use illicit mobile phones?

- Heads of Security reported that illicit mobile phone use was associated with serious organised criminals, those continuing to run criminal business from within the prison and dominant individuals in the landing hierarchy, including gang members. They also saw mobile phones as posing a threat to the good order of the prison, not only in supporting criminal activity and creating instability but also in exposing vulnerable individuals and their families to bullying, exploitation and extortion and providing a stimulus to the culture of violence.

- Prisoners took a more nuanced view. They concurred that the most visible phones were held by individuals with status within the landing hierarchy, often also associated with drug dealing within prisons which they also saw as a driver of instability and the culture of violence. They agreed also that the trafficking of drugs and mobile phones exacerbated the vulnerability of weaker prisoners, who could be required to act as stewards for mobile phones controlled by more powerful prisoners.

- However, they pointed also to mobile phones being more widely used by lower profile prisoners, and concealed from fellow prisoners as well as security staff, and being used for communicating with partners and family. Prisoners saw mobile phones as critical to maintaining and sustaining relationships and facilitating their active participation in family life/relationships. This was particularly key for parents, with mobile phones seen as supporting their ability to continue to ‘parent’ from the inside.

- Prisoners took the view that, given the limitations of the legitimate phone system and the tension and violence associated with disputes around access to it, the presence of mobile phones in prisons also worked to moderate the potential for violent confrontation between prisoners. They also felt that the normalised communications with loved ones enabled by mobile phones reduced the tendency for frustration around the barriers to communications with family to become translated into generalised aggression and violence.

- For younger prisoners, particularly those in Young Offender Institution (YOIs), mobile phones and ‘phone sex’ was seen as a means of both maintaining relationships with (and, in some cases, control over) girlfriends. Time spent on mobile phones especially when interacting with girlfriends was also seen as a way to release aggression, an escape from the tyranny of the relentlessly testosterone-driven landing environment – and simply a source of entertainment and an antidote to boredom.

Lack of consensus on response

- One school of thought, among both some Heads of Security and prisoners, centred on tackling mobile phones by addressing the drivers of demand through enhancing access to legitimate communications. Among the Heads of Security there were fairly polarised views on how far enhanced legitimate phone facilities or in-cell phones would address the demand drivers. Some felt strongly that in-cell phones would lead to greatly reduced demand for mobile phones and enable security to focus on the highest risk and most egregious cases.

- But there was an equally strong body of opinion that was dismissive of the social and family dimensions and felt demand was overwhelmingly criminally driven, with the corollary being that enhancing legitimate phone facilities would do nothing to address this.

//

This content has been republished with permission from the author. See the original here.

Russel Webster is an expert in Criminal Justice and substance misuse, and the author of the blog russelwebster.com