// Interview: Desmond Chin

Commissioner of the Singapore Prison Service

JT: How has SPS transformed over the years and what has been the impact as a result of this transformation?

DC: Twenty years ago, the Singapore Prison Service (SPS) was confronted with two pressing issues — an overcrowded prison system and a shortage of staff due to difficulties in recruitment and retention.

Prison officers were overworked and morale was low. There was also a poor public perception of prison work and the organisation. Even though rehabilitation had always been a part of our mission, rehabilitative efforts for inmates were often fragmented and ad-hoc. The duties of prison officers remained largely custodial. Taken together, these obstacles severely hampered our mission to rehabilitate offenders.

To circumvent the issues, we galvanised all our staff to create a new vision that underscored our aspirations. The visioning exercise, in 2001, saw a clarion call for SPS to make a positive difference in offenders’ lives. Our officers wanted to be instrumental in steering offenders towards being responsible citizens with the help of their families and the community.

After nine long months, our new vision was birthed and we called ourselves “Captains of Lives”. The sense of pride amongst officers about the work they did grew, and the positive experience reinforced the desired mindset shifts and strengthened our officers’ commitment to the new vision.

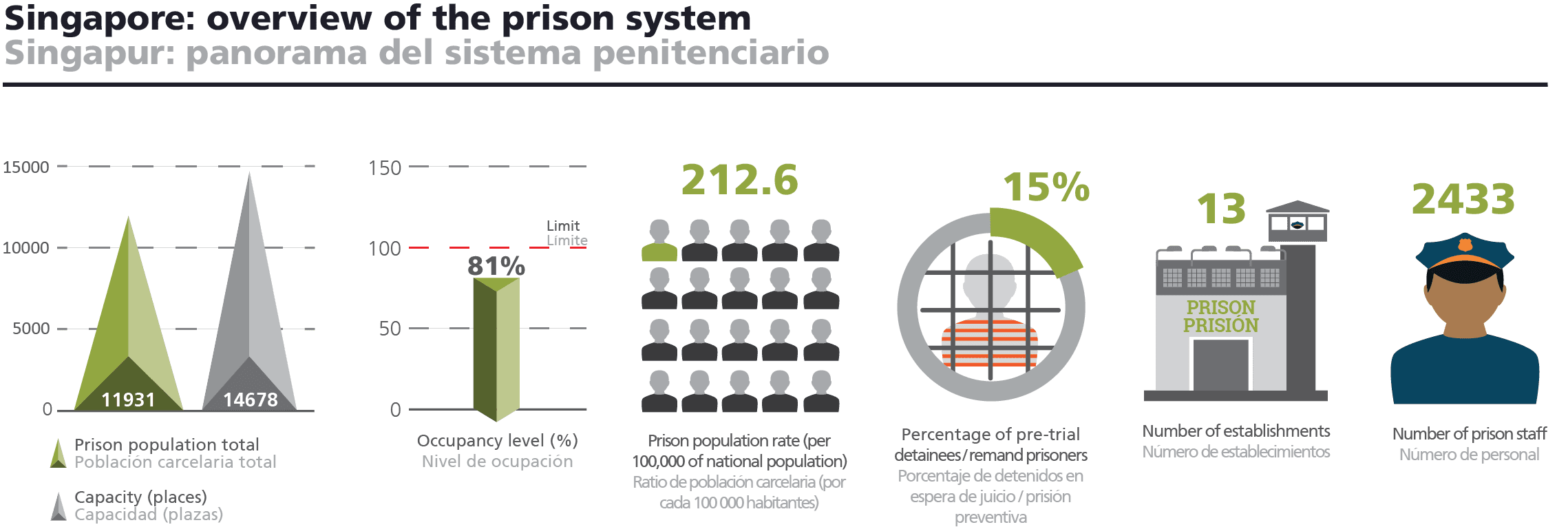

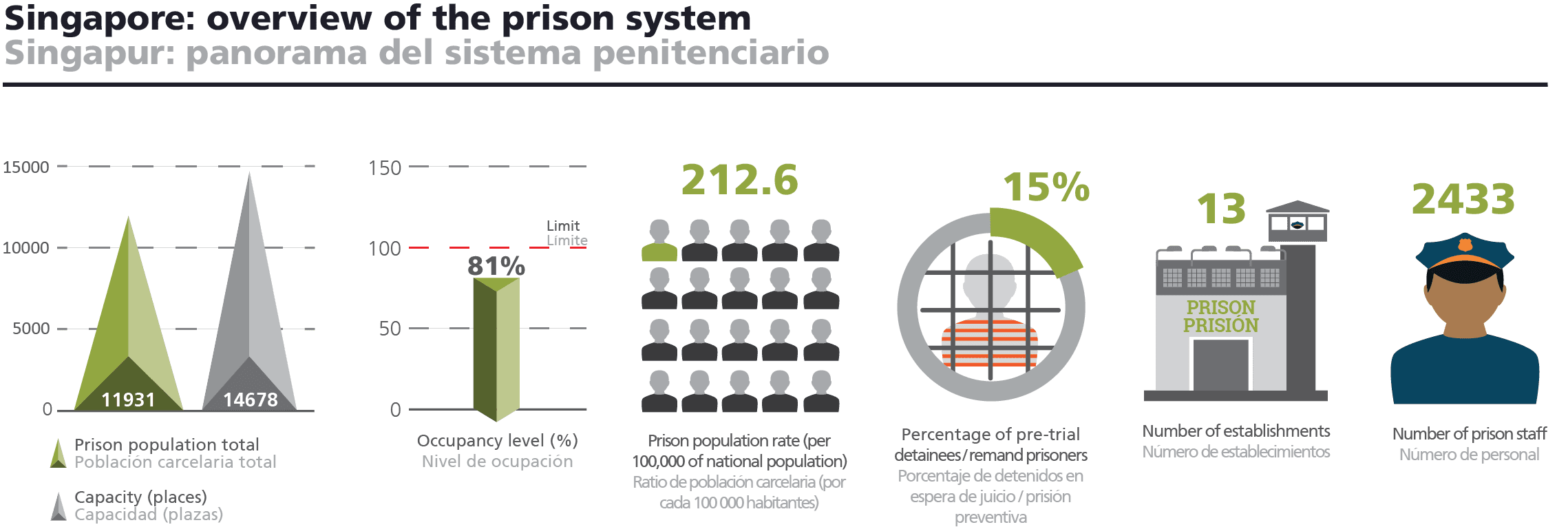

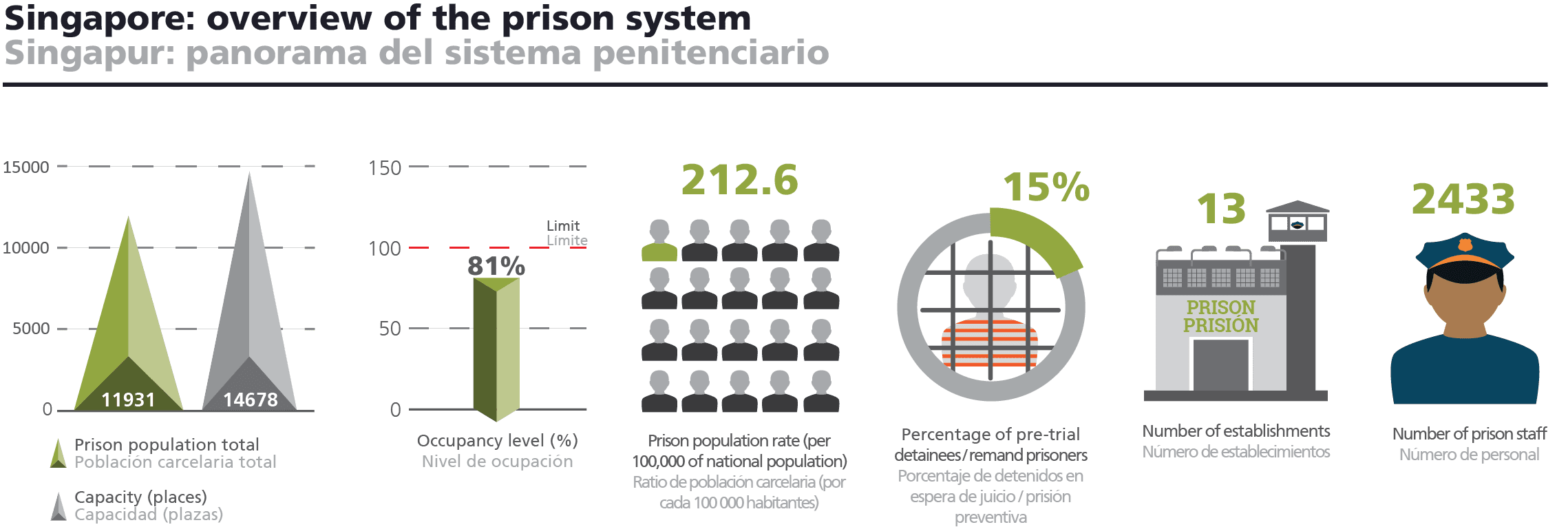

Our manpower problems gradually eased as more qualified officers and volunteers were recruited to serve with meaning and purpose. Our overcrowding situation also improved significantly. The inmate population dropped from more than 18,000 in 2002 to around 12,000 in 2017. Our recidivism rate (for two years) has also steadily declined from over 40 per cent in 2002 to 25.9 per cent for the cohort released in 2015(1).

As the community plays a significant role in helping inmates reintegrate to society, we then strengthened the aftercare support for our ex-offenders with the launch of the Yellow Ribbon Project (YRP)(2) under the ambit of the Community Action for the Rehabilitation of Ex-offenders (CARE) network(3).

Since 2004, the YRP has created awareness, generated acceptance and inspired community action towards second chances for ex-offenders and their families. We work closely with the community to reduce re-offending and scaffold ex-offenders’ reintegration back to society.

Our Yellow Ribbon movement has spread beyond Singapore to other countries, such as the Czech Republic and Fiji. Our fundamental change was the shift beyond security and safety to the effective rehabilitation and reintegration of offenders.

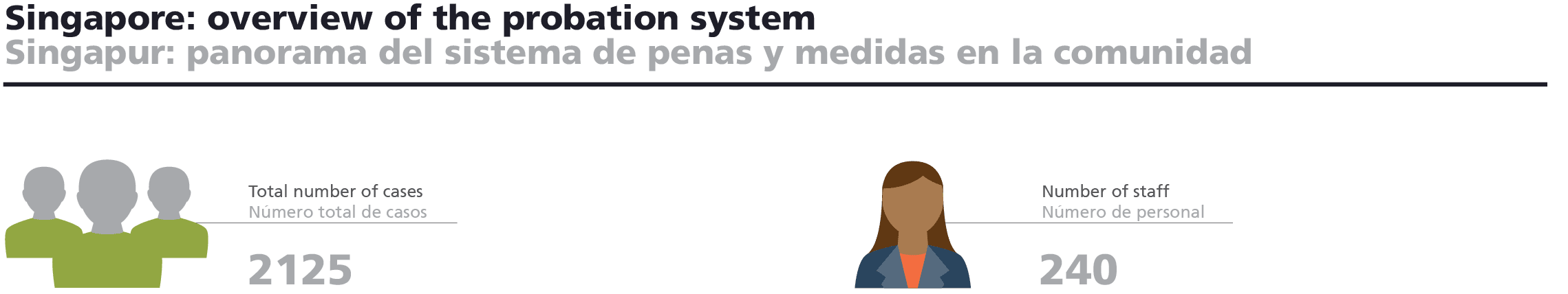

SPS has also moved beyond working within the prison walls to providing structured community reintegration for offenders and ex-offenders. In 2017, more than 2,000 inmates were emplaced on community sentencing.

Through our Yellow Ribbon Community Project, we have also trained volunteers to visit the families of newly-admitted inmates and refer them to available avenues of social assistance. From fewer than 60 grassroots volunteers in 2010, the number of volunteers has grown steadily to close to 900 today. They have effectively reached out to more than 5,000 families of offenders.

These results are a testimony of the good work done by our officers, in close partnership and collaboration with our stakeholders, community partners and volunteers.

Our fundamental change was the shift beyond security and safety to the effective rehabilitation and reintegration of offenders.

JT: What do you consider necessary to do in the future and what role can the prison administration play in a reform endeavour?

DC: Although our overall prison population has fallen, we see an increase in repeat offenders and offenders with drug antecedents. Approximately 50% of the current inmate population has per cent more than five times, and about four out of five inmates in our local prison population have drug antecedents.

Moving forward, we will face an unprecedented age shift due to our declining birth rates. By 2030, more than a quarter of Singapore’s citizen population will enter their silver years—60 years of age and above. For our inmate population, this translates per cent an increased demand for elderly-friendly infrastructure and medical services.

A shrinking workforce would also mean that we have to upskill our staff to ensure they have the relevant competencies. The ageing infrastructure in the Changi Prison Complex (CPC) built since 2004 will need to be upgraded in the near future(4).

In view of these challenges, we are working towards transforming Singapore’s correctional landscape by 2025. We have embarked on our twin key strategies of “Prisons without Guards (PWG)” and “Prisons without Walls (PWW)”. With the shrinking resident labour force, we will operate at a lower manning level without compromising our operational effectiveness.

At the same time, we will be expanding our operations beyond prisons towards community corrections and supervision.

In PWG, we will utilise technologies such as the Near Field Communication, self-service kiosks and facial recognition to automate routine tasks and free staff to engage in higher order rehabilitative work. These technologies, currently implemented as a testbed in our women’s prison, will act as a blueprint for the other institutions within the CPC.

We must always remember that technology is but an enabler and that our staff’s interaction and work with our offenders are what will bring about effective rehabilitation outcomes. In PWW, we aspire to be a correctional agency that does not solely operate within the traditional confines of the prison setting, but one that is committed to providing structured community reintegration for offenders. This is an area that is crucial in reducing recidivism.

Upstream, we will collaborate with law enforcement agencies and the Courts on diversionary sentencing options. Downstream, we will adopt more step-down incarceration and expand the use of community corrections with the support of community partners. Our approach for PWW will be a calibrated one that will include a rigorous assessment and selection process, and robust monitoring and supervision controls.

The introduction of PWG and PWW will fundamentally change the work of our officers.

Our mindset and mission remain the same. We want to break the cycle of re-offending, reduce recidivism further, and continue keeping Singapore a safe and secure home for all.

While we harness technology and forge ahead in our correctional transformation, we are under no illusion that our people, viz. our staff, community partners, and volunteers are the ones who hold the keys to success.

SPS is only as good as the quality of its people. As Captains of Lives, we see our work as having a ripple effect. If we can inspire an inmate to change, it will have an indelible impact on their family, community, and the wider society as well.

JT: Around 10% of Singapore’s prison population are women, which is a substantially higher figure than the world average. How are you dealing with the challenges and special needs of women in prison?

DC: We take cognisance that gender-specific rehabilitation programmes can better address the risks and needs of women offenders, thereby enhancing their ability to succeed post-release. For example, in the area of employment, women offenders face compounded difficulties (e.g. lower wages) and specific issues (e.g. parenting or caregiving responsibilities) that hinder their progress in becoming economically stable.

As such, SPS offers in-care programmes on literacy and customised vocational training for women. We have also introduced a programme aimed at imparting parenting skills to women offenders before their release, helping them to cope with future caregiving responsibilities in the community. This programme encourages women offenders who are mothers to establish positive attachments to their children, helping them model pro-social values for their children after addressing their offending behaviours.

We have embarked on our twin key strategies of ‘Prisons without Guards’ and ‘Prisons without Walls’ (…) we will operate at a lower manning level without compromising our effectiveness.

JT: We have read a number of success stories about how Singapore’s prisoners are rehabilitated, especially with regard to vocational education. SCORE-Singapore Corporation of Rehabilitative Enterprises is the entity responsible for enhancing the offenders’ employability potential.

Could you please tell us more about what programmes exist at this level, how they work, and what results they have had?

DC: Besides aiming at enhancing the employability potential of inmates and ex-offenders, SCORE also garners community support through the Yellow Ribbon Project. To help offenders reintegrate into the workforce, SCORE adopts a seamless approach that covers four main areas: employer engagement, skills training, job placement services and job retention support.

SCORE targets industries and jobs that are economically resilient and offer attractive market-rate salaries. There are currently more than 5,000 partner employers. SCORE also ensures that inmates are equipped with the pre-requisite skills to secure a job by offering training courses that are nationally accredited under the Singapore Workforce Skills Qualifications (WSQ) framework.

The framework is categorised into three levels, starting with generic employability skills, broad industry knowledge and skills, and occupational skills. This alignment allows offenders to pursue further skills, upgrading under the WSQ framework upon their release. About 5,000 offenders were trained through more than 22,900 training places.

A validated job profiling tool has been introduced to better match inmates to suitable jobs. Employers are invited to conduct interviews inside prisons, and 96% assisted secure jobs prior to their release. Post-release, SCORE Job Coaches regularly engage ex-offenders through job coaching and worksite visits to help them develop simple behavioural goals to tackle adaptation challenges and sustain retention at work. About 79% stay on the job for three months and 60% for 6 months.

JT: For several years now, hundreds of prison sentences have been avoided through a sentencing option called Day Reporting Order (Source: “The Strait Times”, 07/02/2018).

What is the intervention of SPS in non-custodial sentences and to what extent do they rely on electronic monitoring technology?

DC: Community-Based Sentencing was introduced in 2011 and it includes the Day Reporting Order (DRO) administered by SPS. First-time offenders who have committed minor offences can be sentenced to DRO; they report to our officers in the community on stipulated dates for counselling and rehabilitation programmes.

Offenders under DRO are also closely monitored via our Electronic Monitoring System (EMS), which elicits compliance to the curfew hours imposed. DRO facilitated by the EMS has pushed our work upstream without involving imprisonment.

Such a regime provides individualised justice while it minimises disruption to the lives of these offenders, easing their reintegration into society. Since its inception, more than 90% of each year’s cohort completed their sentences under the DRO. The high completion rate shows that the DRO is a viable alternative sentencing option.

JT: How has your experience as a board member of the ICPA been and how does this role help you carry out your work at SPS?

DC: SPS is truly honoured to be able to be part of the ICPA. It provides a great opportunity for us to learn from correctional experts all over the world.

We look forward to developing strong ties and fostering close co-operation and collaboration for continuous improvement. We also hope to contribute our learning and experiences to other jurisdictions that seek to transform the lives of offenders, their families and their community.

Notes:

(1) Singapore Prison Service annual statistical publication – www.sps.gov.sg/news

(2) Yellow Ribbon Project – www.yellowribbon.org

(3) This network was set up in 2000 to garner great community support and involvement in Singapore. It brings together key players in the community to promote seamless in-care to aftercare support for ex-offenders. www.carenetwork.org.sg

(4) There are currently a total of 13 institutions in SPS, the majority of which are located in the Changi Prison Complex (CPC), in the eastern part of Singapore. The CPC covers an area of about 48 hectares and comprises

three clusters of prisons, namely Clusters A and B, and the Tanah Merah Cluster.

//

Desmond Chin joined the Singapore Prison Service (SPS) in 1990 and has been appointed its Commissioner in October 2016. Throughout his career, he has held key appointments as the Superintendent of Changi Prison, Head Joint Operations and Emergency Planning in the Ministry of Home Affairs, Deputy Commissioner and Chief-of-Staff of SPS. From 2005 to 2010, he served as the CEO of SCORE, the Singapore Corporation of Rehabilitative Enterprises. He holds a degree in Social Work from the National University of Singapore and has completed an International Executive Programme at INSEAD, in 2010.