// Interview: Brigadier Ayman Turki AL Awaisheh

Director General of Correctional and Rehabilitation Centres, Jordan

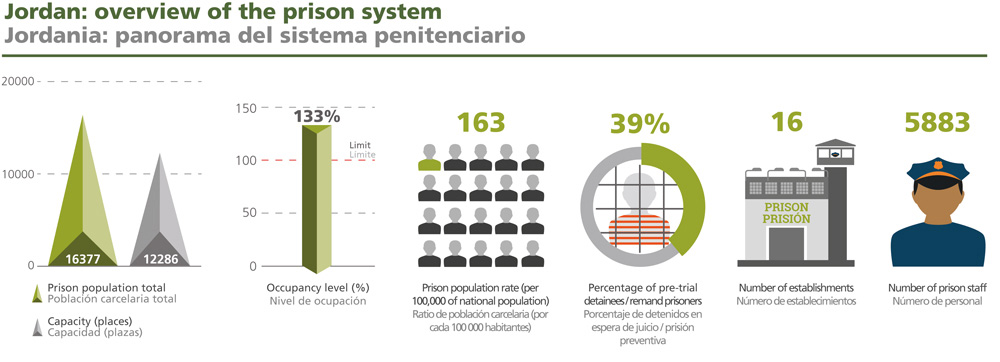

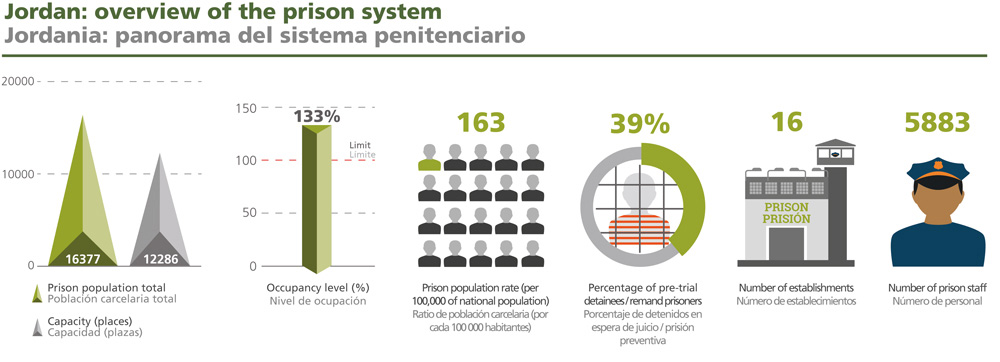

JT: According to data available at prisonstudies.org, in Jordan, the prison population has almost doubled in the last five years, reaching 15,700 inmates in March 2018. In addition, other challenges include an imprisonment rate of over 190 and 40% of pre-trial detention. What strategy is being or should be adopted to change this reality to a more favourable one?

B. AA: Prison overcrowding has negative effects on the rehabilitation process, as well as on the infrastructure itself. In addition, it escalates problems among inmates and makes it difficult for us to provide services.

This dilemma can be addressed through the involvement of all criminal reform institutions, including the Department of Correctional and Rehabilitation Centres.

In this regard, I consider that the following actions should be taken: – implement alternative penalties such as obligatory community service determined by the court, application of a probation system; – amend legislation targeting accused persons, in order to prevent pre-trial detentions (around 40% of the total of inmates in Jordan are in pre-trial or remand detention); – review of penalties for financial crimes, such as the issuance of unhedged checks and unpaid debts, as approximately 30% of the prisoners are held for crimes of this nature; – raise awareness and the level of legal education among citizens through specialised media agencies, identifying the negative effects of committing a crime, especially social exclusion; – identify the core causes and motives of crimes, by focusing on dynamic and realistic researching methods and processes.

The Department of Correctional and Rehabilitation Centres takes several necessary actions aiming to reduce the negative effects of overcrowding, through the increase of recreational, sport and social programmes, and the activation of humanitarian initiatives inside the correctional centres.

In addition, we have allowed more regular and private visits to inmates who, in most cases, can attend the celebrations and events that are organised by the Department. Moreover, they can be allowed to attend private and personal occasions including funerals of first-degree relatives. Furthermore, convicted prisoners are granted scheduled conjugal visits, with specific provisions.

Key elements in the reform process of the correctional service in Jordan consist essentially of developing an integrated response to address the problem of overcrowding (…)

JT: In September 2017, Criminal Procedure Law amendments have been endorsed and the Minister of Justice has noted that “imprisonment as the sole penalty has historically caused harm to the families of the convicts and society in general (…) the introduction of other corrective measures as alternatives to prison is aimed at rehabilitating convicts, citing community service, psychiatric rehabilitation and electronic tagging, which have been introduced to the new version of the Penal Code” (Source: “Criminal Procedure Law amendments endorsed”, Jordan Times, 09 September 2017).

What practical results have emerged from that legislative change?

B. AA: Alternative sentences come in several forms including community service for the public interest. Due to the signing of memoranda of understanding between the Ministry of Justice and various Ministries and official institutions, the convicted persons may carry out community service in departments under the purview of those organisms.

The scope of application of these penalties is somewhat limited; they are only for people convicted of simple criminal acts, such as traffic offences, minor abuse and thefts, and who are not known to be main or repeat offenders.

Then, there is community-based control, which is determined by the court for a period of no less than six months and no more than three years; another sanction is conditional supervision in the community, either with the individual undergoing a rehabilitation programme, or determined by the court in order to assess and improve the behaviour of the offender.

The implementation of non-custodial criminal sentences is still in its initial phase, given that the legislative amendment that allows the application of alternative penalties was first implemented on the first of March 2018. So far there have been no significant changes in the reality of correctional and rehabilitation centres.

JT: What are the main principles underpinning the correctional reform process in Jordan and to what extent have its goals been achieved?

B. AA: Key elements in the correctional services reform process in Jordan consist essentially of developing an integrated response to address the problem of overcrowding, with the aim of: improving the correctional environment, care and services provided to prisoners; reducing the recidivism rate by preparing rehabilitation and reintegration programmes targeting freed prisoners, to help them adjust their deviant behaviour and enable them to acquire knowledge and a job, to facilitate their subsequent integration into their communities, and developing psychosocial and social rehabilitation programmes to help inmates integrate into their communities and enable them to overcome what is known as “admission shock” and “release trauma”.

In addition, we need to work on the capacity-building of our correctional staff, while emphasizing respect for human rights and treatment in accordance with national and international law. Of course, it is also fundamental and necessary to maintain order within correctional centres and reduce possible risks, as well as to establish specialised programmes to deal with new crimes. Finally, activating the role of governmental, non-governmental and international stakeholders is paramount.

Through continuous work, we have already achieved several goals. With a direct impact on the quality of life of detainees, our successes include: the creation of prisoner councils in correctional and rehabilitation centres; the launch, in September 2018, of a website to receive applications for private visits with inmates: 2893 applications were received of which 1628 have been deferred thus saving time, effort and expenses for the families of prisoners; a magazine for inmates that is already in its 13th edition – this publication is edited by the Department of Programmes and Public Relations of the Correctional and Rehabilitation Centres and the content revolves around prison management, agreements with international organisations and all prisoners’ concerns, also featuring articles and poems and covering events; the improvement of food portions served to inmates, as well as the improvement of the cafeteria and the increase of canteen products; the increase in phone calling periods, in addition to the increase of telephone booths; the extension of the length of visits; and the updating of the TV shows to which inmates have access.

Other equally important aspects were the establishment of committees within the correctional centres to go through humanitarian aid requests (financial aid, transfer of prisoners and contributions to funerals); the strengthening of interconnection channels and communication with counterparts, in particular through the establishment of regular meetings; the identification and processing of security vulnerabilities, in cooperation with other departments, and the ongoing review of security plans.

Technology is progressing rapidly, so it is critical that the Department of Correctional and Rehabilitation Centres keeps up with that development.

JT: Has there been international support in the process of correctional reform in Jordan?

B. AA: We are supported by a few relevant international organisations, such as the German foundation for international legal cooperation (IRZ), the United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute (UNICRI), the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), Penal Reform International (PRI), UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), and the European Union. We receive regular calls for our staff to participate in workshops, seminars and international conferences. In addition, we also count on the support of international organisations in conducting training workshops and seminars focusing on the reform process. Other organisations, such as the Red Cross, have provided some health care support through medical equipment and supplies.

JT: Is there any technology that has been implemented and/or is going to be implemented? And what role do technological developments play within the correctional system?

B. AA: Technology is progressing rapidly, so it is critical that the Department of Correctional and Rehabilitation Centres keeps up with that development. The goal is for it to reflect positively on staff’s performance as well as on the services we provide to inmates and their families.

Our initial actions include electronic requests for private visits with inmates; the use of a Remote Trial System and hearing of prisoners’ testimonies, through technological devices directly linked to the court halls. Also, for several years now, court orders have been received electronically, which prevents falsifications.

Soon, requests for transfers of inmates between centres will also be made electronically. Moreover, we plan to implement the use of electronic monitoring to track offenders.

centre, Jordan

Reasons for prisoners’ extremism, irrespective of religious affiliation, are a sign of the reform process’ weakness and of prison overcrowding.

JT: How is the Jordanian Correctional and Rehabilitation Administration supporting global endeavours related to preventing and countering radicalisation and extremism?

B. AA: Generally, correctional and rehabilitation centres around the world are considered a breeding ground for extremism, especially as a result of the direct influence of other prisoners.

Reasons for prisoners’ extremism, irrespective of religious affiliation, are a sign of the reform process’ weakness and of prison overcrowding, which, in turn, result in the mingling of Al-Takfiri ideology supporters (who consider it legitimate to kill non-believers or infidels) with the rest of the inmates.

In addition, some inmates resort to this ideology, seeking personal protection and benefits from extremist inmates who belong to terrorist organisations, because of their ignorance towards religion and their erroneous beliefs about atonement for their sins.

The Public Security Directorate (represented by the Department of Correctional and Rehabilitation Centres) has alerted about extremism and is working hard to contain the Al-Takfiri ideology in our correctional and rehabilitation centres.

Hence, we have been implementing a series of programmes, that are part of short-term and long-term plans, aimed at changing the prevalence of wrong intellectual trends and beliefs among the group of prisoners that professes extremist ideas.

Our efforts are also directed at preventing the spread of these ideologies among both other inmates and the centres’ staff who deal with this group; therefore, we are taking all precautionary measures.

The first step is to categorise this group, placing them in private suites and rooms, isolating them from the rest of the inmates, as well as studying their cases. It’s important that we conduct personal evaluations of the inmates, determining their personality, its impact on themselves and the rest of the inmates.

Furthermore, we assess the extent of their criminal offences. This group must be subject to constant security surveillance and its health and psychological status must be monitored and followed-up.

Developing programmes of intellectual change, while trying to bring them back onto the right track is also beneficial to those inmates, which is done through religious lessons and lectures by the religious and psychological guide in the Centres.

Also, we are focused on activating the role of the religious guides/advisors, as well as on reviewing the libraries’ books to identify those that incite and/or encourage Al-Takfir and religious exaggeration in order to put an end to their circulation among the inmates.

There is also a need to allocate the police staff that deals with these groups of inmates daily, raising their competence through training and specialised courses and lectures in this field; and setting forth preventative and awareness/educational programmes directed at the Correctional Centres’ staff against extremist ideology and thought.

To further understand how much they are influenced by the Al-Takfiri ideology, we must monitor the inmates’ questions and inquiries to the Centres’ religious guides, and then analyse them from a security and religious point of view, identifying any possible characteristics that determine if these inmates still possess the Al-Takfiri ideology or not.

We have a cognitive behavioural programme aimed at achieving the psychological and social balance of those inmates holding extremist views, as they usually suffer from several psychological, cognitive and behavioural problems acquired before entering the Correctional Centres or upon their arrival. Thus, this programme not only provides symptomatic treatment and psychological and social counselling for inmates but also facilitates an easier and smoother implementation of other programmes, always with an integrated and comprehensive approach.

//

Brigadier Ayman Turki AL Awaisheh joined the police service in 1985 and since then served in different police departments such as the Criminal Investigation Department, the Metropolitan Police, the Judicial Executive Police, the Office of the Attorney General, and Department of Correctional and Rehabilitation Centres. He also administered Zarqa, Irbid and Alkarak cities police departments and has been the director of three Correctional and Rehabilitation Centres (Juwaidah, Gafgafah and Swaqa). He holds a bachelor’s degree in Law from the Police Science Faculty and a master’s degree in Security and Management Strategies, both from the Mutah University of Jordan.