// Interview: Major General Dr Tamás Tóth

Director General of the Hungarian Prison Service

JT: Prison overcrowding leading to poor detention conditions resulted in a severe condemnation by the European Court of Human Rights in 2015 (pilot judgment of Varga and Others v. Hungary case, of 10th March 2015). Besides legal costs, the state had to pay between €3,400 and €26,000 in damages to each claimant and there were several of them. In addition, you were urged by the Court to ensure an appeals system to provide adequate compensation to people who have, based on the convention on human rights, had their rights debased. (Source: Strasbourg human rights court makes final judgement on Hungarian prison conditions, Erdon.ro 2015.06.13).

What changes has the Hungarian prison system undergone following that ECRH ruling?

TT: I find it important to emphasize that the European Court of Human Rights has suspended the evaluation of applications submitted due to the conditions present within Hungarian institutions. The reason behind this decision is the fact that the change of certain areas of legislation, enacted from 2017, makes it possible to evaluate complaints and compensation requests within the Hungarian legal system as well.

Providing a legal remedy that is available nationally was an important expectation of the Court. Following the introduction of the remedy system, the Court actually rejected a claims application submitted by a prisoner due to the fact that this prisoner had not resorted to using the national remedy procedure before seeking the aid of the Court.

The principle of the preventive remedy option is that if a prisoner experiences conditions that may violate certain fundamental human rights (mostly the lack of required living space and other violations regarding living conditions), then he or she may issue a complaint to the governor of the institution responsible for the incarceration and may also seek legal remedy for previous iterations of imprisonment allegedly spent among such conditions.

Should a convict receive compensation, then that amount is liable for further deductions based on other legal claims, restitution determined as a result of a felony and reparation for damages but shall not be the subject of further deductions over these.

Obviously, besides introducing legal remedies available in national legislation, it was also indispensable to further expand the capacity of our service, in which we have had several significant achievements.

JT: The increase of non-custodial sentences is naturally conducive to the reduction of prison overcrowding.

How would you describe the development of non-custodial sentences and to what extent does the prison service work in collaboration with the probation service?

TT: I firmly believe that the use of alternative sanctions and measures is indispensable for facilitating the prisoners’ successful reintegration into society and preparing them more efficiently for release.

A great example of this is the institution of reintegration custody, an option that has been present in Hungary for three years. The system is by principle an opportunity for the convicts to spend the last part of their incarceration at home, with the use of electronic monitoring equipment. The convicts may only leave the premises of their homes for several, pre-determined reasons, and through a pre-set route. This system has proven itself internationally as well and is in use in several countries. Our experiences so far are favourable since this system helps post-release reinsertion into the family and social environment and alleviates prison overcrowding. Time spent within reintegration custody is counted into the total duration of the incarceration.

Of course, success cannot be guaranteed merely by putting a tracker on the convicts. We also strive to provide substantive measures and options for the prisoners that help their reintegration. A significant proportion of the prisoners does not possess marketable qualifications, skills or specialised knowledge, which is a great challenge since the lack of these attributes makes it difficult to become employed, even in the case of people with clean records. Due to this challenge, we strive to provide assistance to the prisoners, the majority of whom takes part in formal education or vocational training and the number of those currently employed is also high.

As regards the extent of the collaboration between the prison service and the probation, I would like to emphasize the role of the probation service. All the opportunities and measures that I mentioned before would not be complete and effective without the work of our colleagues in the field of probation supervision. It is important to add that, in 2014, all the probation-related tasks that are relevant to the prison service were moved under the jurisdiction of the Prison Service. The resulting situation was by no means a common one, since, in most European countries, the probation services function as separate entities.

Last year, our colleagues addressed the probation supervision and aftercare-related issues of almost 5,000 prisoners, out of which more than 80% was capable of establishing an employment contract through their help. Therefore, this joint leadership structure has proven effective in our case. I believe that we are very productive and effective in this field and thus would like to include even more people into aftercare programmes in the future.

Over the last few years, we have created 2,000 new rooms, mostly using prisoner workforce. As a result, our general occupancy level has reduced from 143% to 123%.

JT: We have learnt that plans are afoot to build a large prison and eight smaller facilities by 2019 at a cost of €176 million.

What exactly does the infrastructure expansion plan consist of, and to what extent will it help in solving the prison overcrowding issue?

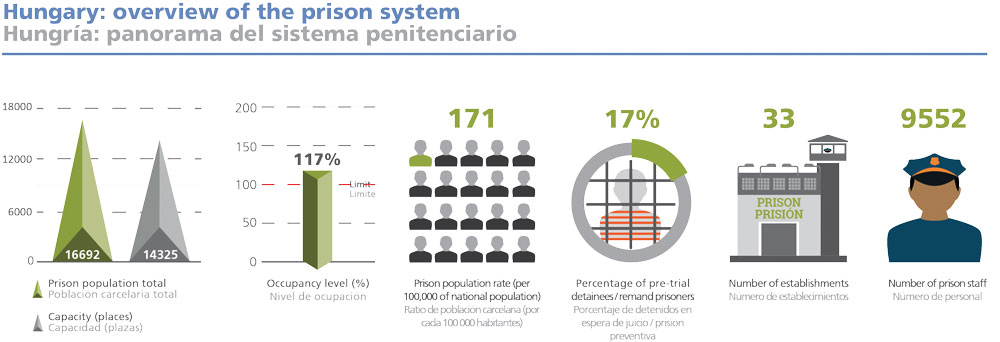

TT: We began our capacity expansion programme in 2010, with the restructuring of already existing sections and wings coupled with cell mergers and continued with new capacities established within the premises of our vacant plots. Over the last few years, we have created 2,000 new rooms, mostly using prisoner workforce. As a result, our general occupancy level has reduced from 143% to 123% in the last four years.

Currently, the preparation for the construction of new prison institutions and one health centre is in progress. During the beginning of 2019, a new institution capable of housing 500 prisoners will be put into operation. Whilst building this new prison, most construction-related tasks were completed with the use of prisoner workforce. Those convicts who participated in the construction received their qualifications through formal vocational training organised by the Hungarian Prison Service and continue to do so.

Not only do the prisoners contribute to the construction of the buildings, but also to the production of the furniture and equipment to be used within them. Within the structures provided by the limited companies of the Hungarian Prison Service, they produce the cell doors, rails and several other tools that are indispensable for prison facilities.

JT: New infrastructure generally means new design, new conditions and new technology. To what extent are these new prisons equipped with technologies, and what is the state of affairs of technological advancements in the prison system?

TT: Obviously, we strive to meet the security requirements in a way that fully conforms to the demands and conditions of the era. I firmly believe in openness and the use of modern methods and measures, which is something I expect from the executives and subordinates as well. The active and fruitful participation in the work of related organisations and attending international conferences and meetings is something we can all benefit from professionally through getting to know the best practices our partners follow and employ.

One such occasion provided us with the idea of introducing a mobile device that the prison guards in service within sections, wards or workplaces can use to acquire all the pertaining information of the inmates under their custody and do all this without being within a standard office environment. The testing of the system is currently on-going, with vastly favourable experiences. This tool facilitates the job of our colleagues on duty within prisons and helps them immensely.

Another significant development in use from mid-2018 is our very own web shop, through which contact persons can order food items and hygienic supplies for a prisoner with just a few clicks. The parcels assembled this way are submitted to the prisoner within three business days, without incurring any postage fees.

Besides technical developments, we also focus on making sure that the working conditions of our staff members are on par with the requirements of the era.

JT: While on the one hand the objective must be to eliminate the problem of prison overcrowding, on the other hand, there seems to be counterproductive legislative changes in Hungary: a law has just been passed that criminalises the homeless (Source: Homeless people face prison in Hungary after tough new law is passed, Euronews 22/10/2018). Furthermore, since 2010 petty theft can be punished with custody, and, also, a law from 2012 allows for automatically changing a fine or community service to confinement without hearing the offender in case he/she fails to pay the fine or carry out the work. Moreover, in 2017 a bill was passed that allows automatic detention of asylum.

How do you see such legislative changes and to what extent will they impact the prison service under your leadership?

TT: Although it is not my field of expertise, regarding the topic of residing on public premises, I find it important to emphasize that the legislation is chiefly focused on motivating the people in question to make better use of the system dedicated to the care and support of the homeless. This system is a dedicated framework with professionals, experts and social workers cooperating jointly. All of them are specialised in caring for people who live under such conditions.

Regarding the prospective increase in the number of tasks the organisation will have to take care of, I would like to emphasize that during trainings and further trainings, our staff members receive a comprehensive and substantive preparation for their successful conduct in duty, which means that they are more than capable of handling these tasks in a professional and effective way which corresponds to the requirements set by law as well.

We strive to meet the security requirements in a way that fully conforms to the demands and conditions of the era.

JT: There are prisons in Hungary under public-private partnerships (PPP).

How do these public-private prisons work, how do you assess the presence of the private sector in the prison service, and whether the PPP model is to be extended to more establishments?

TT: In Hungary, currently two institutions operate under the “PPP” framework. Although the foundations of operation are the same in the case of both institutions, their architecture is vastly different. Based on the provisions of the contract made between the state and the operators, our service is only responsible for the staffing of these institutions while everything else is taken care of by the contracting partner. They are responsible for the day-to-day operation, alimentation, clothing, laundry services, medication, office equipment, computers etc.

Although in the last decade we did not have truly negative experiences with the system, it will definitely require a thorough professional and financial evaluation when the contract expires.

I would like to add that we are not planning any new “PPP” prisons, which of course also means that the system will not be involved in the new institutions and the health centre which I have mentioned before.

//

Dr Tamás Tóth graduated from the Hungarian Police College with a degree in Investigation, and from the Eötvös Loránd University, Faculty of Law, with a degree in Law. He joined the Hungarian Police in 1994 as a detective. From 2003, he was Deputy Chief District Commissioner, from 2005 to 2010 he was Chief District Commissioner, following which he became the Chief Police Commissioner of the Budapest Metropolitan Police. He was the Deputy Director General of the Hungarian Prison Service from 1 July 2014, and in November 2016 was appointed Director General.