Article

Claire Machan, Inês de Castro & Ana Rita Pires

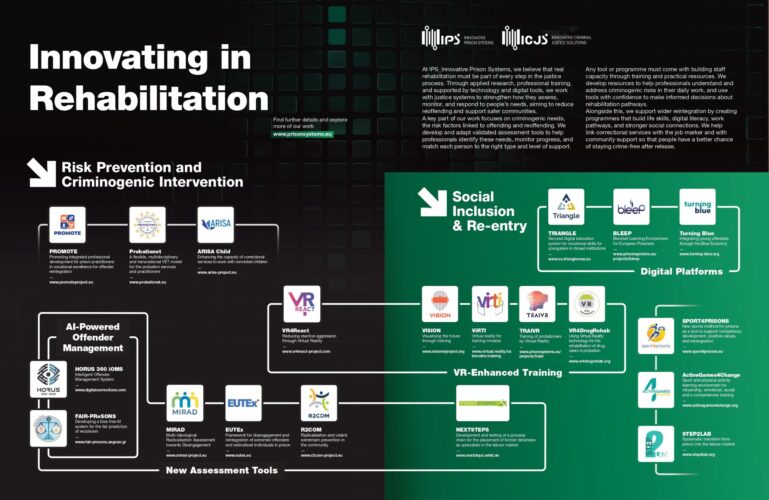

Across jurisdictions, the imperative to reduce reoffending and promote safer societies has placed offender rehabilitation at the forefront of criminal justice reform. While “tough on crime” models once dominated correctional policy and practice (Petrosino et al., 2022), a robust body of evidence now supports rehabilitative approaches that more comprehensively address the root causes of offending and foster long term desistance (Lutz et al., 2022).

As our understanding of human behaviour, psychology, and social dynamics has deepened, so too have the strategies and techniques employed in rehabilitation. Nonetheless, the overarching goal remains consistent: to disrupt patterns and cycles of criminal behaviour, reduce the chance of reoffending (increase desistance), and foster the conditions for positive change (Maier, 2021). The rehabilitation process therefore must begin at the earliest point of contact with the justice system and continue through custody, release, and reintegration in the community.

Tools for justice: Supporting evidence-based risk assessment and management

Evidence-based frameworks such as the Risk-Need-Responsivity (RNR) model (Andrews & Bonta, 2010), and desistance theory (Maruna, 2001; Sampson & Laub, 1993) have significantly reshaped how justice systems engage with individuals in conflict with the law. These models underscore the importance of tailoring assessments and interventions to the unique profiles of individuals, and the specific contexts of their communities.

Central to this effort is the recognition that rehabilitation must be responsive to the individuals’ risk factors and criminogenic needs (Andrews & Bonta, 2010; Seewald et al., 2024). In turn, we strongly advocate that high value is placed on the application of validated assessment tools to monitor individual progress, and support professionals to regularly review and adapt rehabilitation plans accordingly to individual evolving risks and needs.

While validated assessment tools are essential, their utility is easily constrained by poor integration into operational decision-making. In many systems, these tools are employed in an isolated way, detached from the broader offender management processes, thereby limiting their influence on rehabilitation planning, programme allocation, and ongoing case monitoring.

Accordingly, IPS’s approach to offender management solutions places structured assessment tools throughout the custodial life cycle. Within systems such as HORUS 360 iOMS, core risk and needs instruments are embedded into staff workflows from intake and initial classification to programme referral, supervision, and release planning. This ensures that decision-making is grounded in consistently updated, individualised data.

Hence, the system supports dynamic case management, facilitates targeted interventions, and enables staff to monitor behavioural change and adapt responses accordingly.

Tackling bias in assessment tools in the age of AI

It is imperative, however, to acknowledge the inherent limitations in many widely used risk assessment instruments, i.e., most established tools were developed and validated predominantly on samples of white male offenders in the United States. This raises concerns about their generalisability to non-U.S. populations, women, and ethnic minorities (Cavanaugh et al., 2019; Fazel et al., 2023).

At the same time, we are seeing a marked shift toward the adoption of artificial intelligence (AI) in streamlining risk assessment processes for offenders. These systems aim to increase efficiency and consistency in predicting recidivism and informing sentencing or release decisions. Albeit, growing evidence highlights the risks of algorithmic bias in the datasets used to train these tools, which often embed existing inequalities (Farayola et al. 2023).

Numerous studies have highlighted the limitations and discriminatory impacts of widely used recidivism prediction and risk assessment tools – such as COMPAS, OxRec, HART, and PATTERN, particularly when they are calibrated using non-diverse or historically biased datasets. As such, there is a marked need to explore the impact of sensitive characteristics (gender, race, ethnicity etc.) on the design and application of AI-based predictive risk-assessment models.

Recognising this critical gap, as part of the transnational FAIR PReSONS partnership, we are developing a bias-free AI system for the fair and ethical prediction of recidivism. With a strong emphasis on gender equality and alignment with EU non-discrimination legislation, the model not only seeks to mitigate systemic bias in risk assessment tools, but also to empower legal professionals, through training on the ethical and effective use of AI in rehabilitation-focused decision-making.

Assessment tool adaption

Equally important, is the active commitment to developing and adapting assessment tools to enhance accuracy and effectiveness in risk assessment, case management and rehabilitation planning. There is a need for more specific assessment tools, that target risk factors and needs associated with specific emerging offence types that are of growing public, political and security concern across the EU.

One such example is the adaptation of the Individual Radicalisation Screening (IRS) Tool¹ for implementation during exit programmes towards inmates’ deradicalisation.

By reviewing and adapting the different dimensions, indicators, and protective items’ phrasing (or adding new items, if appropriate) the tool now accommodates an enhanced gender-sensitive approach, as well as addresses specific driving ideologies, including Right-Wing Extremism (IRS RWE), and Islamist Extremism (IRS IE).

Equipping the front line: Why staff training is imperative for successful rehabilitation

While individually tailored risk assessment tools and interventions provide a framework for rehabilitation, their effectiveness depends on the capacity of correctional professionals to implement them in the practical operations of justice settings, and ensuring positive outcomes for justice-involved individuals.

A key area where staff training needs attention is the supervision of children in conflict with the law, wherein a gap persists between training policy intentions and quality training practices (Skelton & Tshehla, 2019). A comparative training needs research study (CECL et al., 2024), employing survey and qualitative interview methods across 10 EU Member States, revealed common training deficiencies, and a need for shared minimum standards in what concerns a more child-centred approach to rehabilitation.

To address this, we led the development of a digital training course within a broader partnership effort, combining theory with practice to address frontline knowledge and skill gaps across modules related to child right, developmental psychology, trauma, child-friendly communication and family engagement. Early feedback, from implementing in 6 languages (English, Bulgarian, Greek, Italian, Portuguese and Spanish), indicates the programme’s success in improving professional knowledge of relevant legislation, child development and greater confidence in applying practical child-friendly justice approaches. These results are now informing discussions on minimum competency standards, structured induction training, and interdisciplinary collaboration in youth justice practice across Europe.

While compliance with international standards is considered a key driver for investing in staff training (Töyrylä, 2022), there is a duel need to ensure the safety and retention of staff. Research indicates (Baggio et al., 2020) that institutional prison factors, such as overcrowding, lack of (trained) staff, and insufficient rehabilitation support are significantly associated with levels of inmate misconduct, infractions, and violence – ultimately, increasing the risk of injury and stress for prison officers, and leading to high rates of absenteeism, job dissatisfaction, and staff turnover.

One area where there is a significant lack of effective prison programmes is in addressing (reactive) aggression regulation, along with a lack of training for professionals. Recognising this demand, as part of the VR4React partnership, we have developed an innovative training approach to:

a) enhance prison officers’ cognitive and behavioural strategies (i.e., de-escalation tactics; practical intervention strategies; rehabilitation support) to effectively respond to, manage, and prevent reactive aggression, achieved via a self-paced theoretical e-Learning course, complimentary by immersive VR-based training; and

b) a VR-based intervention for individuals with a history of reactive incidents, aimed at improving emotional regulation and impulse control.

Following its implementation across several EU Member States, the ‘VR4React’ training approach has since won “Best Innovation Project” in Romania (awarded by the National Administration of Prisons), and in Poland, has been included in the ‘National Catalogue of Projects’ – to be implemented across the entire prison system, thus, demonstrating I’s quality practical content and high utility.

Extending the rehabilitation scope: Supporting socio-labour transitions

While evidence-based, bias free risk assessments, effective custodial (criminogenic) interventions and staff training are essential for enhancing rehabilitation, they alone are insufficient to ensure sustainable re-entry outcomes for justice-involved individuals (Jonson & Cullen, 2015).

Recent research highlights the critical role of non-criminogenic needs in shaping successful rehabilitation outcomes (e.g., Jung et al., 2024). Upon release, these include areas such as mental health, housing stability, access to education, employment opportunities, digital literacy and positive social relationships. Addressing these needs may not directly reduce criminal behaviour in a causal sense, but they are essential to supporting individual well-being, autonomy and the capacity to lead a socially responsible life.

In this topic, research has highlighted the transformative role of structured digital access in overcoming digital exclusion and supporting the transition back into a connected world (Reisdorf & Rikard, 2018), with digital literacy now recognised as essential for education, employment, and everyday life (McDougall et al., 2017; Seo et al., 2020). Despite this, institutionalised youths are predominantly excluded from digital opportunities due to the prioritisation of security within detention facilities (Brites & Castro, 2022).

To address the rehabilitation needs and uphold the digital rights of young people deprived of liberty, we have developed a secure online learning environment for use in closed institutions in partnership with 8 organisations from Belgium, Portugal and the Netherlands. Importantly, via co-creation session with youths themselves, region-specific content, on topics such as personal development, employability, and social responsibility, have been adapted to address local needs, languages, and contexts, enhancing its cultural relevance. Through multi-staged piloting in the 3 partner countries the TRIANGLE platform was positively received as inclusive, engaging and accessible learning environment, empowering incarcerated youth with educational resources, digital skills [in line with the EU Digital Education Access Plan (2021-2027)], and guidance on available vocational trainings.

Two key roadblocks to the effective socio-labour reintegration of justice involved individuals lies in the matching of their (typically low-level) skills set to appropriately matches foundational trainings that are tailored towards current labour market skills shortages to ensuring successful employment upon release. One industry that may aid in overcoming these barriers is the European Blue Economy (BE), which is expected to double its employment by 2030, yet is faced with a critical challenge of drawing young people into maritime careers (World Bank Group Jobs, 2023).

As such, through a collaborative consortium, we have led the development of the ‘Turning Blue Roadmap’, which has successfully scoped the key BE sectors holding a high potential for employing justice involved youths, as well as identified the key competencies required for entry level positions within them. This has informed the creation of a ‘From Prison to the Blue Economy’ model, entailing a sector awareness training programme – to introduce youths to BE careers (adapting to different national contexts), and a job matching platform – to establish a bridge between BE employers and prisons.

Virtual Reality as a driver of vocational training motivation

While institutional (e.g., practicalities, access to materials) and situational (e.g., current utility of education) are often barriers to the uptake of training opportunities within prison environments, individual motivation (dispositions) is a transversal hurdle for many incarcerated individuals (Manger, Eikeland & Asbjørnsen, 2018). VR-based training however, can served as an innovative tool in this sphere, offering an immersive, hands-on training medium that enables the exploration of potential vocational training opportunities, and an initial gamified dive into hands-on experiences to become aware of essential job-related skills (Alshaer, 2023; Smith et al., 2023).

Recognising this motivational barrier, we aim to lead the way in employing VR as a complementary motivator for enrolment in rehabilitation and reintegration initiatives. Linking back to the need to direct justice-involved individuals towards training within labour markets matched to their skill level and employment prospects upon release our VISION-VR modules introduce incarcerated persons to careers in the culinary and hospitality sectors.

Similarly, our ViRTI-VR modules introduce roles in the construction sector, exploring trades like bricklaying or carpentry through immersive learning. The purpose in these scenarios is to stimulate vocational interest, reduce anxiety around unknown labour markets, and help participants envision a viable post-release career path.

Charting the future of rehabilitation – Innovation, integration, and impact

As justice systems navigate increasing complexity and rising expectations, the future of rehabilitation lies evidently lies in multi actor, evidence-informed and tech-enabled service delivery models that begin early and extend beyond release to support both the individual, as well as the professionals and communities around them.

As previously highlighted, digitalisation is a key enabler of this transformation. From virtual learning environments and AI-supported risk assessment and case management, technology is expanding access to personalised, scalable, and continuous support – both in custody and in the community. Digital tools have the potential, not only enhance service delivery and support staff resourcing, but also, to support data driven decision-making and system accountability.

We need to continue actively exploring these frontiers, integrating digital solutions, cross-sectoral partnerships, and applied research to support justice systems in becoming more responsive, rehabilitative, and resilient. We believe that justice systems across Europe and beyond should adapt similar strategies, where the emphasis is on building skills, strengthening social ties and promoting long-term change. To make rehabilitation truly effective in the next decade, prison systems must evolve into flexible, multi-stage frameworks that integrate risk prevention with social reintegration.

Rehabilitation is not an endpoint – it is a continuous, collaborative process that requires partnership, innovation and the belief that everyone deserves a second chance. And, with the right vision, tools, and commitment, it can be a catalyst for lasting change.

¹ The Individual Radicalisation Screening (IRS) Tool, originally developed under the R2PRIS project,

encompasses different dimensions related to inmates’ (vulnerability to) radicalisation process through a thoughtful, careful appreciation of a wide range subset of gender-responsive indicators (i.e., risk items) related to the type of ideology and the moment which the assessment takes place (i.e., during the implementation of a rehabilitation programme).

References

Alshaer, A. (2023). Virtual reality in training: a case study on investigating immersive training for prisoners. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, 14(10), 196-201

Andrews, D. A., & Bonta, J. (2010). The Psychology of Criminal Conduct (5th ed.). New Providence, NJ: LexisNexis/Anderson Publishing.

Baggio, S., Iglesias, K., Gonçalves, J., Heller, P., Mundt, A. P., & Wolff, H. (2020). Mapping the health-related correlates of violence in prison: A systematic review. The Lancet Public Health, 5(7), e371–e380.

Brites, M. J., & Castro, T. S. (2022). Digital rights, institutionalised youths, and contexts of inequalities. Media and Communication, 10(4), 369–381.

Doichinova, M., Stoyanova, M., Machan, C., Becker, H., Venâncio, R., Gomes, J., Pires, A., Antonelli, S., Scandurra, A., Stroppa, R., Zagarelli, R., Fernández-Castejón, E. B., Carreras Aguerri, J. C., Román, M. (2024). Reforming Youth Corrections: Comparative report assessing the training needs of prison and probation staff working with convicted children.

Farayola, M. M., Tal, I., Malika, B., Saber, T., & Connolly, R. (2023, August). Fairness of AI in predicting the risk of recidivism: Review and phase mapping of AI fairness techniques. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security (pp. 1-10).

Jonson, C. L., & Cullen, F. T. (2015). Prisoner reentry programs. Crime and Justice, 44(1), 517-575.

Jung, S., Thomas, M. L., Robles, C. M., & Kitura, G. (2025). Criminogenic and Non-Criminogenic Factors and Their Association with Reintegration Success for Individuals Under Judicial Orders in Canada. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 69(12), 1688–1706.

Lutz, M., Zani, D., Fritz, M., Dudeck, M., & Franke, I. (2022). A review and comparative analysis of the risk-needs-responsivity, good lives, and recovery models in forensic psychiatric treatment. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13,

988-905.

Manger, T., Eikeland, O. J., & Asbjørnsen, A. (2019). Why do not more prisoners participate in adult education? An analysis of barriers to education in Norwegian prisons. International Review of Education, 65(5), 711-733.

Maier, M. (2021). Offender Rehabilitation in International Criminal Justice: Towards Implementation of Tailored Rehabilitation Programs. Case W. Res. J. Int’l L., 53, 269.

Maruna, S. (2001). Making Good: How Ex-Convicts Reform and Rebuild Their Lives. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Petrosino, A., Fronius, T., & Zimiles, J. (2022). Alternatives to youth incarceration. In E. Jeglic & C. Calkins (Eds.), Handbook of issues in criminal justice reform in the United States (pp. 685–700). Springer.

Reisdorf, B. C., & Rikard, R. V. (2018). Digital rehabilitation: A model of reentry into the digital age. American Behavioral Scientist, 62(9), 1273–1290.

Sampson, R. J., & Laub, J. H. (1993). Crime in the making: Pathways and turning points through life. Crime & Delinquency, 39(3), 396-396.

Seewald, K., et al. (2024). An updated evidence synthesis on the Risk-Need-Responsivity (RNR) model: Umbrella review and commentary. Journal of Criminal Justice, 92, 102197.

Seo, H., Britton, H., Ramaswamy, M., Altschwager, D., Blomberg, M., Aromona, S., Schuster, B., Booton, E., Ault, M., & Wickliffe, J. (2020). Returning to the digital world: Digital technology use and privacy management of women transitioning from incarceration. New Media & Society. Advance online publication.

Skelton, A., & Tshehla, B. (2019). Child Justice in South Africa: Children’s Rights Under the Spotlight. Pretoria University Law Press.

Smith, M. J., Parham, B., Mitchell, J., Blajeski, S., Harrington, M., Ross, B., … & Kubiak, S. (2023). Virtual reality job interview training for adults receiving prison-based employment services: A randomized controlled feasibility and initial effectiveness trial. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 50(2), 272-293.

Töyrylä, E. (2022). A global perspective on prison officer training and why it matters. Penal Reform International Blog.

Wilson, H. A., & Gutierrez, L. (2014). Does one size fit all? A meta-analysis examining the predictive ability of the Level of Service Inventory (LSI) with Aboriginal offenders. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 41, 196-219.

World Bank Group Jobs (2023). Blue Economy: Structural Transformation & Implications for Youth Employment. Solutions for Youth Employment (S4YE). Thematic Discussion Notes Series, 6.

Claire Machan is the Rehabilitation, Reintegration, and Community (Rehab) Portfolio Coordinator at IPS_Innovative Prison Systems. She holds a MSc in Forensic Mental Health and is upon completion of a PhD in Experimental Psychology. With over eight years of academic experience in applied forensic psychology, she has worked with prison services, LEAs, victim support, and the military delivering education and training. She is an Expert Member of the ICPA Juvenile Justice Committee and active in global research societies including EAPL, BPS, APA, and SJDM.

Inês de Castro is Head of the Risk Prevention and Criminogenic Interventions Unit, within the Rehab Portfolio at IPS. A clinical psychologist with a post-graduation in psycho-criminology, she specialises in forensic risk assessment, psychological evaluations, and inmate support. Inês is a certified trainer, delivering sessions on case management and the RNR model. She has co-authored a book chapter on forensic assessment and published in the Prison Service Journal.

Ana Rita Pires is Head of the Social Inclusion & Re-entry Unit, within the Rehab Portfolio at IPS. She holds a Master’s in the Science of Emotions from the University Institute of Lisbon (ISCTE-IUL), with advanced training in Emotional Intelligence and Mental Health. She has lectured on psychophysiological methods and completed internships in international relations and occupational health, bringing a multidisciplinary approach to social reintegration.