Interview

Mathilde Steenbergen

Director-General of the Belgian Prison Service

With a career spanning over two decades in the justice field, Mathilde Steenbergen’s journey has taken her from managing individual facilities to shaping national policies. Now at the helm of the Belgian Prison Service, she is navigating complex issues such as overcrowding, staffing shortages, and the implementation of innovative correctional approaches.

This interview delves into her perspectives on these pressing matters, exploring how Belgium is modernising its prison infrastructure, addressing systemic challenges, and balancing humane detention practices with public safety. From the ambitious expansion of detention houses to leveraging public-private partnerships for facility management, Director Steenbergen sheds light on the strategies driving change in the Belgian justice system.

Stepping into the role of Director-General at a time when Belgian

prisons face significant challenges, what are your top priorities for

the Prison Service?

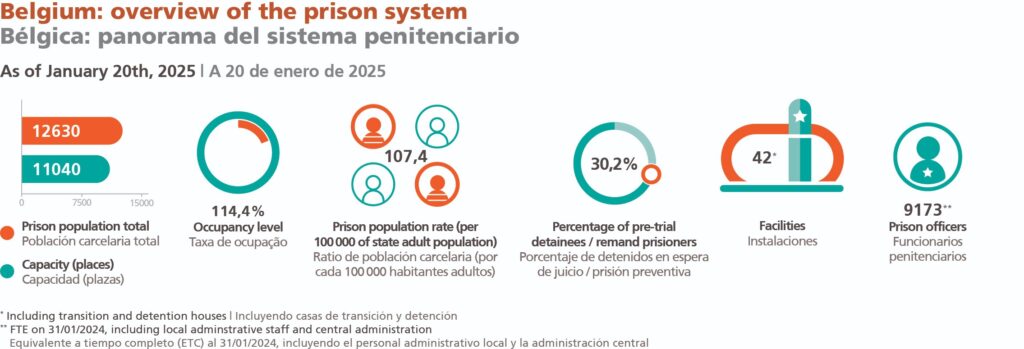

MS: We are facing a situation regarding overcrowding that I believe is quite intense even when compared to most other countries – each week, our prison population increases by the hundreds. At the moment, it is impossible to advance on policy change, so we have to accept new arrivals placing them in spaces that are already beyond capacity, which is deeply frustrating.

This creates a significant risk for society, as many leave prison without meaningful support or improvement. Their original problems are often compounded, and that’s simply unacceptable.

We must change this dynamic so that we can return to the real purpose of our work: helping individuals start better lives. A prison should provide an opportunity for growth and positive change, not amplify the issues that brought people there in the first place.

Other significant priority is related with our staff. Until a couple of years ago, we were able to overcome staff shortages. But in the past four to five years, we’ve had the opportunity to open several new facilities, which is both a positive development and a challenge. The challenge was finding enough staff to fully operate these new prisons.

For example, when we opened the prison in Haren, we needed around 1,000 new staff members. In the same year, we also opened the new prison in Dendermonde, further adding to the demand.

Initially, the plan was to close older facilities as we opened these larger prisons, reallocating staff and hiring only the additional personnel needed. But because of the ongoing overcrowding crisis, we had to keep the older facilities running. As a result, we had to recruit entirely new teams for both Haren and Dendermonde.

On top of this, we also needed staff for other facilities, such as the renovated prison in Ypres and the opening of our first detention houses. Altogether, in two years we had to find around 2,000 new staff members. This also meant that we couldn’t focus on reinforcing staff levels in the existing facilities, and now we are facing significant staff shortages once again. This issue is compounded by a broader trend seen in many countries: it is becoming increasingly difficult to recruit enough staff.

This has left us with a double-edged problem: we don’t have enough staff, and we don’t have enough experienced staff who have received the full training we want to provide. With overcrowding still a major issue, this makes the situation incredibly challenging at the moment.

JT: Belgium has used public-private partnerships for “Design, Build, Finance and Maintain” (DBFM) contracts for several of its prisons built in the last decade, and continues relying on this model for upcoming projects. In a DBFM project, the design, construction, financing and maintenance of public infrastructure or a public building are tendered in a single agreement and entrusted to a private party or a partnership of private parties.

The use of DBFM contracts in the Belgian penitentiary sector has

sparked both optimism and debate. What would you say are the

main advantages and disadvantages of this model?

MS: We come from a situation where the prison park was heavily outdated and unadapted, and we are currently catching up. Given the very large needs and the urgency with which they had to be realised, a DBFM formula was chosen. So this has led to a faster concretisation of our projects, but in addition, the very big advantage lies in the continuous maintenance that is carried out.

We had significant problems with maintenance in our older facilities. Many things were broken and left unfixed, which created a lot of frustration in those prisons. When the government makes financial cuts, it is often the upkeep funding that is affected.

On top of that, another department is responsible for our infrastructure. So maintenance involves dealing with heavy procedures, insufficient budgets, and staffing challenges.

With DBFM contracts, even when the government makes budget cuts, the conditions in these prisons are protected.

The contracts guarantee a minimum level of certainty that the money will be there to pay the bills and maintenance is handled by our private partners. This allows us to focus on our own core responsibilities. Yes, it costs more, but in the long term, we also lose a lot of money in the older prisons by not addressing issues promptly, often resulting in unusable cells, and a general reduction in the quality of detention conditions.

The newer facilities also offer a level of quality we simply don’t achieve in the older ones, from better maintenance to the use of modern architecture techniques. There are technicians continuously on site, where it is very difficult for the government to recruit them themselves. We also have better care through facility services.

Personally, I am a big fan of this approach, but there’s one important condition: it requires proper oversight. It’s not a system where you can step back and assume everything will run smoothly on its own. We must ensure the public sector remains in the lead and that private partners don’t take advantage of a lack of oversight. We have to work together.

In some prisons, this collaboration works very well; in others, it is more challenging. That’s why we need to invest in building clear and balanced relationships, based on confidence and strong governance. I must say that our experience is quite positive and when managed properly, we can strike a good balance between control and trust. I believe we are on the right path.

How are you evaluating the success of modern facilities in operation, for example the Haren prison, and what adjustments can be made to improve outcomes in future projects?

MS: Haren is a very specific project. It has now been open for about three years, but I think it is still too early to definitively say what all the advantages and disadvantages are. We are still in the process of maturing there, especially since we faced significant pressure to open it quickly. Our staff is not yet fully prepared, and there’s still work to be done to help Haren reach its full potential.

That said, there are already clear positives. The modern infrastructure provides better living and working conditions than the old prisons in Brussels. Projects like Haren also allow us to evolve with the times, using concepts that aim to promote more meaningful detention. Architectural features and the use of green spaces play an important role in the well being of both detainees and staff.

However, there are also challenges. One of the biggest drawbacks is the sheer scale of Haren – it is simply too big. Managing a prison with 1,000 people is extremely difficult. In our other facilities, which typically have an average capacity of around 312, it is much easier to establish unified management and a consistent philosophy. In Haren, communication with staff is much more complex, and ensuring that everyone works in the same way is a significant challenge.

The village structure, while innovative, also has its drawbacks like requiring far more staff to operate effectively. It is an example of how certain operational realities are not always fully accounted for in the

planning phase, and once the facility is built, adapting can come at a very high cost.

Another issue is the long lead time for these projects. By the time they are implemented, the initial concept can sometimes feel outdated.

For example, in newer prisons, we are already moving towards more open structures and integration into the surrounding environment – things we are learning from projects like Haren. To address these challenges, we ensure continuous monitoring of all new projects. We regularly consult the directors of these prisons to understand what works and what does not This feedback allows us to improve with each new facility.

Belgium has been at the forefront of integrating technological

innovations in the construction of new facilities. Do you have

plans for modernising older prisons to bring them in line with the

technological advancements of the new infrastructure?

MS: Over the past 20 years, we’ve made substantial investments in prison infrastructure, and today, around one-third of our prison population is housed in new or modernised facilities. We are gradually moving towards having half of the population in these settings. We’ve also been able to close some outdated facilities, such as Forest Prison in Brussels last year.

When we carry out full renovations – like in Ypres, for example – we are able to incorporate new technologies. In Ypres, we added an extra level to the prison, renovated it in phases, and enlarged the facility while modernising it.

Another example is the open prison in Ruiselede, which will be mostly rebuilt. It will be larger but will still follow the philosophy of small scale detention, with a total capacity of 145 people, divided into different levels and groups.

It is worth noting that modernising older prisons comes with significant challenges, like installing cables or addressing power issues. As a result, while we try to upgrade these facilities, the level of technological integration is never quite the same as in new or fully renovated prisons. One area where we believe that Belgium is leading in innovation – both in new and older facilities – is providing technology directly to individuals in detention. For instance, every cell in Belgian prisons is equipped with a phone and a television, which is rare or even unique in Europe.

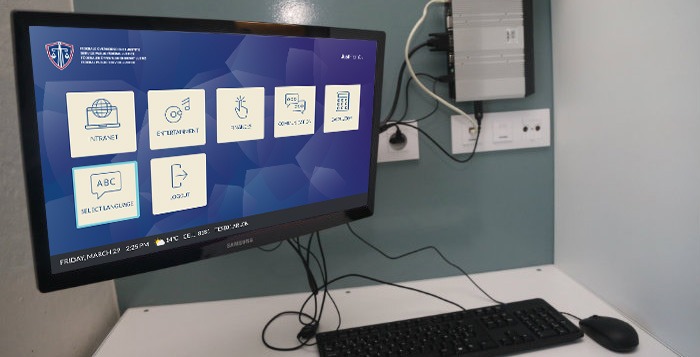

We are rolling out a secured digital platform to expand these services. This platform will offer various possibilities: detainees can communicate, order canteen items, take classes, and even rent entertainment options like movies or games.

We are also investing in modern detection technologies. For instance, we are rolling out smartphone detection devices and a trace detection device to combat smuggling of dangerous substances. Other innovations include intelligent camera systems to identify suspicious activity, manage contraband risks, and improve reporting and accountability. Another area of focus is addressing drone-related threats. We’ve initiated several projects to test C-UAS (Counter-Unmanned Aircraft System) technologies.

How do the new transition houses and detention houses fit in the

future of Belgian corrections?

MS: In Belgium, we currently have three types of prisons. First, there are the traditional prisons, which are divided into open, semi-open, and closed facilities – this is the system we’ve always had. Then, we’ve introduced two newer approaches: transition houses and detention houses.

Transition houses function like halfway houses. These are managed by private partners, and are intended for the final part of a person’s sentence. Typically, 12 individuals live in a house, supported by professionals who help them reintegrate into society.

The second new system is detention houses, which have been introduced over the past two years. Detention houses are designed as an alternative to classical prisons, aiming to prevent individuals from entering traditional prison systems altogether. While they share some similarities with transition houses, there are key differences. Detention houses are managed directly by us, and they accommodate a maximum of 60 people, though we are working to reduce this number to 40 in the new units being developed. We are currently building nine new detention houses, all designed with this smaller capacity in mind.

For now, detention houses are focused on housing individuals serving sentences of up to three years, which means the security risks are lower. This allows us to operate with fewer security measures.

The primary goal of detention houses is to create a meaningful detention experience from day one. The focus is on integration, not as something that happens after a prison sentence but throughout the detention period itself.

MS: This helps avoid the collateral damage often associated with traditional incarceration.

The staff in detention houses are specially trained and selected for their ability to work with people, rather than simply guarding them. The setup is also very different: individuals live together in groups of up to 15, sharing a kitchen and living room, and they each have their own private room rather than a cell.

There’s a strong emphasis on autonomy and responsibility. Residents are expected to organise their daily lives, including cooking meals, cleaning, and managing household tasks. Most go to work outside the facility, and those who don’t are given work to do inside. The staff’s role is to guide and support them as they take responsibility for themselves.

For me, this is the future. Detention houses represent a shift toward a more rehabilitative and humane approach to justice, emphasising personal accountability and integration into society.

How do you balance between the need for increased capacity

and the longer-term goal of reducing incarceration rates through

alternative solutions? And how do you ensure that detention

houses fulfill their purpose of avoiding traditional prisons, rather

than being used to house people who could otherwise be serving

community sentences?

MS: My biggest concern for everything we do is net widening. If we look at the policies of the last 10 to 15 years, our incarceration rates have been steadily increasing each year. But at the same time, the number of alternative measures has been rising at double that rate. When you compare Belgium’s statistics with global figures, we are fairly average in terms of the number of inmates per 100,000 inhabitants. However, for alternative measures, we are far above average. This is all part of the net widening problem, which is, in my opinion, one of the fundamental challenges of the modern world. For detention houses, though, I believe we’ve managed to avoid it so far – but we need to ensure it stays that way.

One key reason why detention houses haven’t caused net widening yet is that judges do not decide whether someone goes to a detention house or a traditional prison. Judges only determine if someone is sentenced to imprisonment. After that, it is up to the prison service to decide where that sentence is served. But if that changes, I am certain we would see net widening happen almost immediately.

What does concern me, though, is the potential for an indirect net widening effect. As we take pride in the concept of detention houses and highlight how they help individuals prepare for a better life, there’s a risk that judges may feel more comfortable sentencing someone to incarceration, which could inadvertently lower the threshold for imprisonment. That’s a significant risk. We’ve seen this with our internees. We created like almost 1000 places outside prison for them. The result is that the number of internees in prison went from over a 1000 to 500 in 2018. Today we are again over a 1000 internees in prison.

I believe this isn’t just a challenge for Belgium but for all of Europe. We are increasingly moving toward more repressive policies, and it is driven, to some extent, by populism.

Criminology, as a science, is often counterintuitive. Harsher, more repressive approaches don’t necessarily lead to better outcomes, and in many cases, they make things worse. We need to explain this clearly to people, even if it’s not always an easy message to convey.

Mathilde Steenbergen

Director-General of the Belgian Prison Service

Mathilde Steenbergen is the director-general of the Belgian Prison Service of the Federal Public Service of Justice. After obtaining master’s degrees in criminology and public management, Mathilde started her career in 2001 as prison director in the Bruges prison. After 13 years working in prison, she changed course to work in various cabinets of Belgian ministers, always in the field of justice. She worked as a prison advisor and justice advisor for the Minister of Justice, and the deputy prime minister respectively. In 2020, she assumed the position of director of the Strategic Justice Office, before becoming director-general of the prison service in September 2024.

Advertisement