Interview

Ángela María Buitrago

Minister of Justice and Law, Colombia

Since taking office in July 2024, Minister Ángela María Buitrago has been at the helm of Colombia’s justice system. With a comprehensive approach that balances institutional coordination, human rights, and modernisation, she is leading efforts to improve legal accessibility, rethink incarceration, and expand restorative justice initiatives. In this conversation, she shares insights into her vision, the Ministry’s priorities, and the ongoing transformation of Colombia’s justice landscape.

What do you consider the fundamental pillars of your administration?

AMB: The Ministry of Justice in Colombia has multiple responsibilities, covering several key areas. Our work revolves around four main pillars.

The first is access to justice, which involves coordination with all judicial institutions, as well as the development and implementation of public policies for legislative proposals.

The Ministry also has to manage a second aspect that is very important, which is drug policy. In this area, the we are responsible for shaping public policy and defining the projects and programmes to be implemented.

On the other hand, we have a continuous role in Transitional Justice¹. In this context, we are working within the Special Jurisdiction for Peace, where the Ministry has specific obligations under the legal framework that governs this process.

Additionally, the Ministry oversees the prison and penitentiary system. The challenge I took on as Minister has been to ensure that none of these areas are neglected.

Could you share how you are setting new standards to humanise and modernise the infrastructure of Colombia’s prison system?

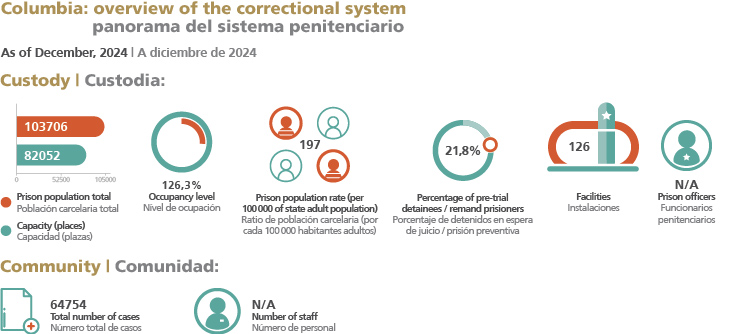

AMB: We have 127 penitentiary centres across the country, which we commonly call “ERON” (Spanish acronym for National Prison Establishments).

When we examine the structure of detention facilities, whether ERONs or jails, many are extremely old and lack the proper conditions for a restorative approach, protection, and dignity. This means that when many of these centres were built, the approach was strictly punitive—for example, the La Modelo facility in Bogotá is over 100 years old.

Today, our approach requires us to adapt spaces, redefine priorities, and develop new constructions, all while ensuring human dignity is at the core of these efforts. This shift is seen in La Picota, a much newer prison build as a high-security facility.

Within La Picota, which includes high and medium-security sections, we are focusing on adapting structures to meet the specific needs of the prison system. These needs centre around rehabilitation, preparation for release, and the development of individuals skills and abilities so that, once their sentence is served, they can reintegrate into society under suitable conditions, including the possibility of starting their own businesses.

This has led to initiatives such as “Zasca” and “Renacer”, which aim to teach a trade, craft, or profession to individuals while they are incarcerated. We are working to expand these initiatives across all prisons, especially in the area of garment production.

For example, convicted persons now produce uniforms inside penitentiary centres. Those who participate not only receive sentence reductions — with three days of work counting as one day off their sentence — but are also able to learn a trade and receive financial compensation from industries that employ this workforce.

We are also developing agricultural production projects. Calarcá is a prime example of this, in collaboration with the Coffee Confederation of the Quindío region. Here, convicted persons learn the entire coffee production process — from planting, harvesting, and roasting to preparing and selling the coffee in public establishments. The profits generated go to the workers themselves and partially to the prison’s operational needs.

Another key initiative is the “Agricultural Colony” model. These low-security prisons teach agriculture, livestock management, and self-sufficiency skills, with the goal of making prisons self-sustaining over time.

This type of training has a profound impact. We very nice success stories of people who had never worked in agriculture or livestock farming before, yet learned these trades in prison. Many are now grateful, as they see farming as a viable livelihood after their release.

In these agricultural colonies, those in custody enjoy greater freedoms compared to maximum-security prisons. However, our vision is that all prisons should eventually provide rehabilitative opportunities like these.

Of course, this is not an ideal system yet. Overcrowding remains a significant issue, but we have made notable progress.

Overcrowding rates have dropped dramatically — from 300% or 400% in some facilities to a national range between 26% to 31%.

AMB: We now have the advantage of having wards where there is no overcrowding. In El Pedregal prison today there is no overcrowding in women, we are in a general range between 26% and 31% of overcrowding, compared to times when we had 300% or 400% overcrowding. We are trying to keep it in a range of this nature and try to lower it with three projects that we have. We intend to deliver at least two of them this year, and another one that would give us more or less between 1,700 and 1,800 more beds for prisons.

Given these problems of prison overcrowding, non-custodial measures and restorative justice are being highlighted as alternative solutions. What can you tell us about progress and plans in this area?

AMB: In the shift towards a more restorative approach, a law was introduced called the Public Utility Law for mothers who are heads of households and are either in a state of vulnerability or under specific circumstances. The idea behind this law is that it allows women to leave prison and serve their sentence outside by working in social service roles or with certain companies. Through this, they gain significant opportunities to see that they can continue on the path of legality.

This measure takes into account how these women end up in the prison system. They are often used by drug trafficking groups, which exploit their vulnerability and involve them in drug-related offenses or other related crimes. Many of these women eventually realise that they do have other options.

This issue is particularly important because we have also seen a shift in the role of women in society. Today, women are often the primary providers for their households. From this perspective, we also recognise the importance of restorative justice, especially when it comes to children and adolescents in the justice system.

This brings us to SREPA (System of Criminal Responsibility for Adolescents), which takes a fundamentally different approach to crime and punishment. It recognises that juveniles require a restorative perspective, rather than a strictly punitive approach.

In this context, there are various mechanisms in place. Aside from the Public Utility Law, there are other legal provisions that not only focus on alternatives to imprisonment but also address cases where individuals have already served a significant portion of their sentence and may be eligible for parole.

Ultimately, we are working to counteract the negative effects of excessive punitivism. Criminal law should not be the ultimate tool for social control—it should be a last resort.

Digitisation has been one of the key pillars in the modernisation of Colombia’s judicial system. How have technological advances improved judicial efficiency and access to justice?

AMB: Digitisation taking hold in the justice sector as a global trend, which means not only recognising the advantages of technology and artificial intelligence, but also developing mechanisms that allow us to improve judicial procedures, access to justice, and case resolution more effectively.

This is a broad and far-reaching transformation. The Ministry of Justice is currently working on a major project in collaboration with the Superior Council of the Judiciary to implement the digital case file. This initiative focuses on interoperability between government institutions, ensuring that individuals have simple, easy, and convenient access to a single platform where they can view their case files and track legal procedures in real time.

As part of this digital transformation, we are not only improving the user experience, making it more personalised and practical, but also expanding the ways in which justice is made accessible to the public.

To that end, we have a series of software applications and digital tools designed for ordinary users. One key application allows for easy online reporting, enabling individuals to file complaints — for example, in cases of domestic violence — and receive immediate assistance.

Given the rapid evolution of laws and regulations, it is essential to provide a clear and accessible way for professionals to determine which laws are in force and which are not.

Beyond creating digital resources for professional training, a key component of this strategy is SUIN-Juriscol, a platform dedicated to the publication, updating, and clarification of legal norms. SUIN-Juriscol serves as a public policy tool that ensures the digital transformation of legal knowledge nationwide. The platform has been widely used, with 12,000 to 14,000 people accessing it at peak times to consult legal information.

We have agreements with the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) to secure funding for digital transformation projects in Colombia’s judicial sector. Looking ahead, the JustiFácil project aims to modernise the judicial services system, ensuring that access to justice is simpler, faster, and more user-friendly for all citizens. We remain committed to this digital transformation, working daily to expand its reach and impact.

¹ Transitional justice refers to the legal and institutional mechanisms used to address human rights violations committed during periods of conflict or repression. In Colombia, this process has been central to the implementation of the 2016 Peace Agreement, particularly through the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP), which seeks to investigate and prosecute crimes from the armed conflict while ensuring victims’ rights to truth, justice, and reparation.

Ángela María Buitrago

Minister of Justice and Law, Colombia

Ángela María Buitrago has served as Minister of Justice and Law since July 2024. A lawyer and PhD in Law and Legal Sociology, she holds a specialisation in Criminal Law, Politics, and Criminology. With over 30 years of experience as a professor at the Universidad Externado de Colombia, she also served as Deputy Prosecutor before the Supreme Court. She has worked with the IACHR and the UN on investigations of human rights violations in Mexico and Nicaragua. She is a trainer of judicial officials in Latin America and an honorary member of procedural law institutes in Colombia and Ibero-America.

Advertisement