Interview

Luis Cordero Vega

Minister of Justice and Human Rights, Chile

What are the main challenges faced by the justice system in Chile?

LCV: The Chilean justice system currently faces a variety of challenges, including contingent, medium and long-term aspects. Over the past 30 years, Chile has undergone a series of progressive reforms in its justice system. Notably, in Latin America, it was one of the pioneers in the implementation of criminal procedure reforms, a transformation that has now been in place for 24 years. This process has not only changed the conception of the justice system but also aspects related to recruitment and case management.

Reforms have presented challenges in numerous areas. Recently, however, the need to reform the criminal prosecution system and related aspects of the criminal procedure and enforcement regime has intensified. This situation, which reflects a regional trend, considers how to understand the enforcement of sentences, not only as a state sanction but also from the perspective of the social reintegration of offenders and the usefulness of prison policies for public safety.

In this context, Chile has placed a special emphasis on reforming its penitentiary policy. Recently, our Parliament has made progress on a long-awaited bill introducing penalty enforcement courts, a piece that was missing from prior reforms. This reform marks a major advance in access to justice, placing a special focus on the protection of victims.

In addition, a reform was introduced to the Adolescent Responsibility Law, creating the Juvenile Reinsertion Service. This law introduced specialised judges, prosecutors and defenders, as well as dedicated hearings. For the first time, criminal mediation has been integrated, a restorative justice mechanism that has generated great expectations among experts. Thus, juvenile justice becomes a pillar not only for the future of the young people involved but also as a means of evaluating how initiatives such as criminal mediation may be successfully applied and possibly extended to other areas of the justice system.

In addition, outstanding human rights processes are being addressed. Chile continues to prosecute criminals for crimes against humanity committed during the dictatorship. Although justice has taken its course, the extensive time that has passed between the committing of these crimes and the issuing of sentences has been a challenge, and the country is in the process of resolving this historical debt.

In view of the implementation of the “National Policy Against

Organised Crime” in Chile, could you explain the objectives of this

initiative, how it specifically addresses the challenges existing within

the penitentiary system and what measures are being taken?

LCV: Criminal organisations have generated intense disruption in Chile. This phenomenon has been observed globally and was exacerbated by the opportunities that the pandemic offered these organisations for expansion. The transnational nature of organised crime has had a special impact in Chile, a country that traditionally observed these organisations from afar.

There has been an increase in violence and illicit activities which impact markets, posing a major challenge for the state. Criminal organisations take on forms that quickly adapt to the law. They have mechanisms for intervention, for injecting illicit resources into markets, etc.

In response to this emerging threat, the country has rapidly developed and implemented the “National Policy Against Organised Crime”, which seeks to effectively combat these organisations.

As Europol’s April 2024 report states, criminal organisations operate in networks and, therefore, the way to attack them is also networked. This is why this policy integrates the work of 17 public agencies. This is complemented by major legislative reforms in areas such as drug trafficking, the implementation of special investigative techniques and the adaptation of institutions that support criminal prosecution, including the police forces and the Gendarmería, the entity that oversees prisons in Chile.

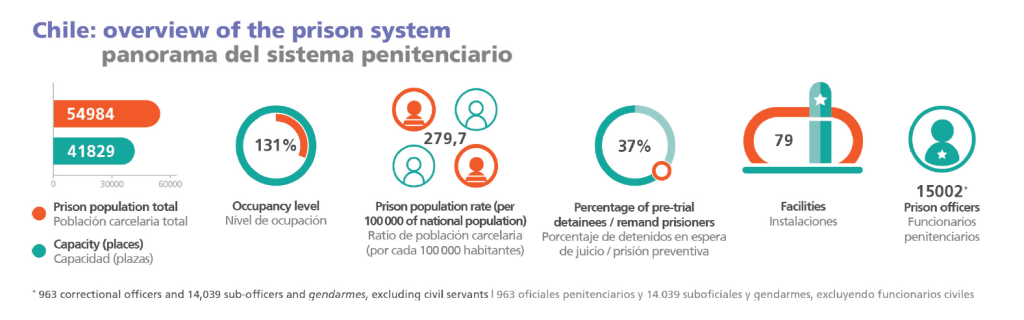

The country has experienced a significant increase in its prison population, reflecting a trend existing in Latin America towards more rigid penal systems.

This increase, especially noticeable over the past two years, has led to overcrowded prisons, which are prone to criminal recruitment without strong prison institutions, both in terms of physical infrastructure and professionalisation.

In response to this, Chile is investing in a long-term prison infrastructure plan, aimed at 2030. This approach not only considers the need to develop prison infrastructure, it also considers adapting prison and sentencing policies to meet the challenges caused by organised crime. It is essential to understand that the overuse of prisons can, in the long run, benefit criminal organisations, since they may serve as recruitment grounds, if adequate segregation and reintegration policies are not applied.

Therefore, prison policy needs to be holistic, considering the entire system, including the serving of sentences in liberty, as key to the longterm success of security policies.

JT: The prison system is overcrowded by over 30%, highlighting the critical problem of overcrowding. Earlier, your Excellency mentioned that the open system is also affected by this congestion.

What strategies are you considering to alleviate this situation in prisons and how do they fit into the change of paradigm that you advocate for the prison system?

LCV: The challenge of prison overcrowding in Chile requires a multidimensional approach that considers more than merely increasing the number of vacancies. For a decade, the number of vacancies remained relatively stable at around 41,000, a period in which the country focused on improving prison standards, especially through public-private investment mechanisms.

The prison fire tragedy of late 2009 marked a turning point, leading the state to adopt policies of decongestion through general pardons and the relaxation of the granting of benefits. However, a decade later, we can see a return to stricter policies regarding these concessions.

On the other hand, we also have the effects of the pandemic, which I believe should not be overlooked. One of these has been the normalisation of the criminal prosecution systems, in other words, taking over the backlog of cases. Another is the increase in violence, which is leading to the intensive use of pre-trial detention.

But at the same time, this situation has meant that sectors of the population are pushing for all punishable acts to be sanctioned with imprisonment, which has resulted in an increase in pre-trial detention and a considerable decrease in conditional liberties. This is taking place not only in Chile but also in other parts of the region. And the effect of all of this is that prison overcrowding is very contingent, but one must consider the long-term perspective.

No public policy on prisons can be sustained over the long term by merely increasing prison vacancies since prison spaces will always be finite.

In this context, our focus is on managing overcrowding, while modernising the prison infrastructure, with a master plan, but taking into account rational prison use.

This leads us to pay special attention to the execution of sentences, an area where recent legislative developments have allowed for effective control in the free environment, facilitating the use of prison for cases where it is really useful and promoting social reintegration as possible.

Considering that the profile of the prison population in Chile is mostly male, young, with low levels of education and no formal work, it is evident that there is a need for strong state intervention to achieve reintegration. Investment in reintegration therefore becomes a key strategy for long-term security, in an attempt to balance current demands with sustainable public policies for the future.

How do you justify the importance of the public-private participation model in the management and modernisation of prisons in Chile?

LCV: Approximately 38% of all individuals deprived of their liberty are in public-private prisons. In Chile, the public-private participation model is characterised by the construction and operation of complementary prison services by private organisations, while the security and reinsertion aspects are state responsibilities.

Chile is updating its infrastructure plan, mainly based on reactivating the concession system within the public-private participation model. This allows us to invest resources appropriately, and to learn from the process.

In the past, the country made some mistakes in the first tender processes, resulting in high costs, but we have been correcting them. This involved a significant reform of the law regulating public-private participation in Chile.

Indeed, the private sector is very efficient in construction, maintenance and in the provision of complementary services such as food and laundry, as well as in the provision of some means of reintegration.

However, the responsibility for reintegration must lie primarily with the state, since it has a higher level of scrutiny and offers much more specific traceability. In the current tenders, we are including more sophistication in the medical services, increasing the offer, especially for psychiatric care, which is crucial in prisons. The public-private participation model is fundamental to implementing an adequate prison infrastructure policy in Chile.

Regarding the open system, what changes are needed to improve

its efficiency and capacity, and are there any specific plans or

initiatives underway to address these needs?

LCV: Strengthening the non-custodial sentencing system is one of our most important structural priorities. Traditionally, this area has received little attention and therefore, limited investment, despite its crucial need.

In response, the first step we are taking is to improve the regulation of sentencing enforcement and to establish penalty enforcement courts. This will allow for more detailed and controlled management, representing major progress towards our objective.

The efficiency of the open system is crucial. If it is effective, we can use prisons more rationally. If it fails, the institutional trend will resort to more intensive incarceration, which not only has a strong stigmatising and personal impact on individuals but also implies high costs for the state and society.

Investing in community-based sentencing is therefore essential. In terms of infrastructure and policy, our direction is clear. We have identified deficiencies in the probation system and we are in the process of creating an appropriate institutional structure to address these needs. A crucial aspect of this effort involves increasing investment in this area.

In addition, we are placing a special emphasis on launching a youth reintegration service. As I mentioned earlier, this programme focuses on interrupting early criminal trajectories, facilitating criminal mediation and offering young people opportunities for future development.

This requires a specialised penal framework, including dedicated judges, defenders and prosecutors. We are currently in the first year of the gradual implementation of this programme, which will be expanded to a larger number of regions over the next two years, until becoming fully operational.

What additional public policies are being implemented for the

modernisation and transformation of the organisational culture in

Chile’s justice system?

LCV: In an effort to modernise and transform the Chilean judiciary system, we can initially highlight the intense recent involvement of the judiciary powers in the reform processes. However, we face a long-term structural challenge: the need to separate judicial governance from the jurisdictional function.

In Chile, we have a bicentennial model in which both roles are the responsibility of the same entity, the Supreme Court. This poses significant obstacles to the administrative modernisation of the judicial system. There has been widespread consensus on this issue, with several past attempts at constitutional reform having been made, although they were unsuccessful.

Critical aspects of this reform include the appointment process, career management and judicial discipline, with special emphasis on the professionalisation and development of judicial careers. This is a longterm perspective that seeks greater integration and better efficiency of the system. On the other hand, Chile has made remarkable progress in the technological field, being a pioneer in the region, even before the pandemic, in the implementation of telematic justice.

The health crisis accelerated and broadened our understanding and use of technology, transforming it from a mere means of support to a fundamental way of exercising justice. This change of paradigm suggests that technology is not only an administrative tool, but it is also an emerging means of delivering justice.

We are therefore addressing public policies that link technological modernisation with the institutional management of the judicial system. This duality of approaches – structural reform and technological advancement – constitutes our main challenge and job of improving the efficiency and effectiveness of the justice system over the long term.

Luis Cordero Vega

Minister of Justice and Human Rights, Chile

Luis Cordero Vega has been Chile’s Minister of Justice and Human Rights since January 2023. An expert in administrative law, he has had an outstanding career in public service and academia, contributing significantly to various legal reforms and public policies. His professional career includes key roles in the Legal-Legislative Division of the Ministry of the Presidency, as well as serving as head of the Evaluation and Control Department of the Public Criminal Defence Office. As an Associate Professor at the University of Chile, he is recognised for his great expertise in institutional design and Supreme Court jurisprudence.

Advertisement