Interview

Maria Rosa Nebel

Secretary of the Penitentiary Administration, Rio de de Janeiro, Brazil

How would you currently assess the prison system in the state of Rio de Janeiro and what policies and strategies do you consider to be priorities for its improvement?

MRN: The Rio de Janeiro Penitentiary Administration Secretariat (SEAP-RJ) is one of the oldest secretariats dedicated to prison affairs in Brazil, and is about to turn 21 years old.

SEAP-RJ was a pioneer in several initiatives, being the first secretariat to establish an intelligence system, which has evolved over the years, culminating in the creation of a Sub-Secretariat of Intelligence. It also introduced the first Prison Ombudsman’s Office, the first Tactical Intervention Group (GIT) and Brazil’s first Prison System Inspector General’s Office, which also became a sub-secretariat.

So, we have a rich history and organisational structure. This consolidated regimental framework makes Rio de Janeiro an example to be followed, with a number of other states seeking to learn from its experience.

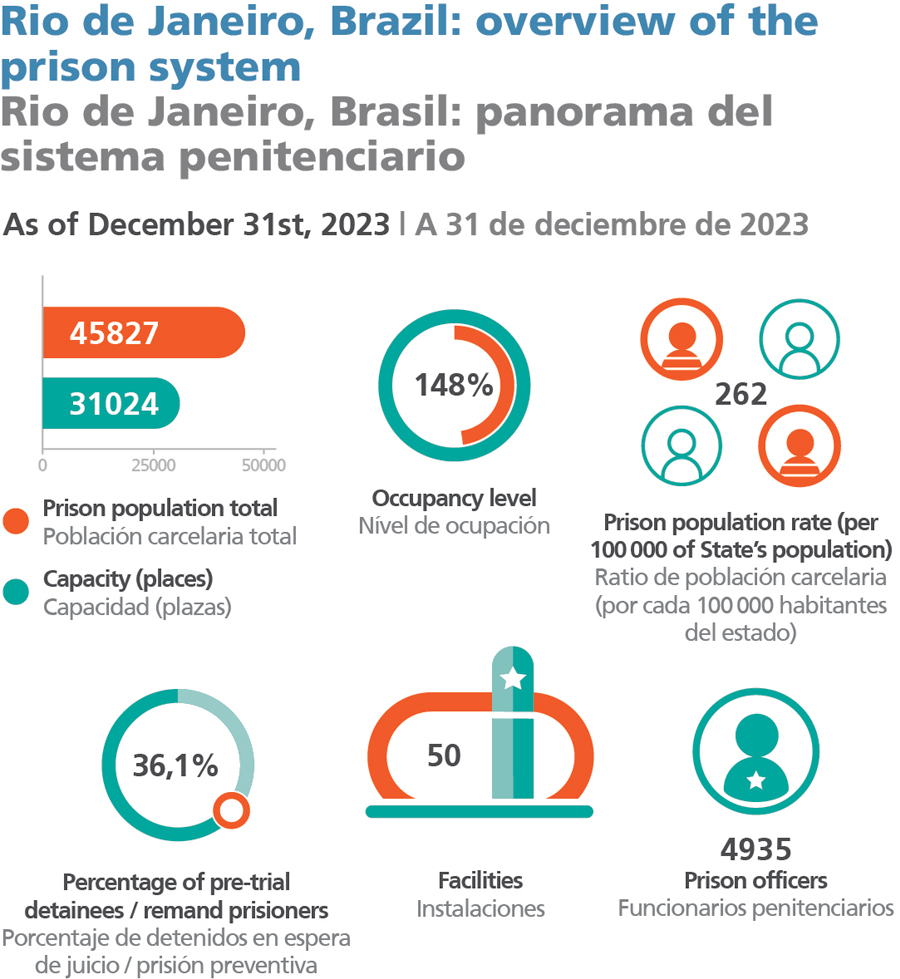

In terms of challenges, our situation is no different from that of other states. Currently, we have a workforce of 42,000 individuals who have been deprived of their liberty, extended over 46 prisons and four hospitals. We have to manage distinct profiles of individuals, many of whom have links to different organised crime factions.

We are committed to making the system more humane, attempting to transform the lives of those who have been deprived of their liberty. Therefore, we have a sub-secretariat that is devoted to re-socialisation through study, work and professionalisation.

One of the main challenges is the professional recognition of our officers, promoting a suitable working environment and providing them with the necessary tools for their daily work.

The Penal Police Officer position is not an easy job. We have to take on a wide range of roles in the process of reintegrating individuals into society.

I do not understate the work of the other police forces, but once they have fulfilled their role of investigating, solving the crime and taking the convict to prison, from then on that individual will spend an average of five to eight years in prison. During this time, the Penal Police are responsible for their qualification, health and well-being.

It is necessary to recognise the enormous importance of these professionals within the state system, emphasising their importance to society, inmates and their families. Furthermore, it is vital to recall that prison officers, many of whom have spent years on duty, have themselves experienced the prison routine for decades on end.

We have endeavoured to support and recognise our civil servants by investing more in qualifications and courses. We are also close to launching a new recruitment process to refresh and increase our Penal Police force, a measure to which the government has been highly receptive.

This focus on civil servants is an essential part of a three-part plan that guides our actions, along with modernisation and transparency.

In terms of modernisation, we have established significant partnerships. Since the beginning of our administration, we have directed our resources towards working together with the National Secretariat for Penitentiary Policy (SENAPPEN), and with the support of FUNPEN, the National Penitentiary Fund.

As a result, we have made a number of acquisitions, including helmets, vehicles and 583 new computers. We are currently discussing plans for this year to spend approximately 60 million reais on a maximum security prison unit in Rio de Janeiro.

This level of collaboration and integration with federal agencies is unprecedented and fundamental to meet the demands and needs of the national prison system. Regarding transparency, talks are underway to strengthen our control systems, such as the State Comptroller’s Office, the Ombudsman’s Office and the Internal Affairs Department, ensuring that all contracts are tendered, something that is unprecedented in the history of our system. This reflects our commitment to rigorous planning, the only way to effectively manage a department of this size.

As a Penal Police Officer, what is your perspective on the importance of including professionals from this speciality in the Prison Secretariat management?

MRN: In the current administration, under the leadership of the governor of Rio de Janeiro, we have been given the opportunity, for the first time, to demonstrate the ability of Penal Police Officers to manage their own secretariat, recognising their unique experience and skills. The responsibility of the Penitentiary Administration is immense, but it is significantly more challenging for those who are unfamiliar with the prison system.

The current management, made up entirely of Penal Police officers, shows that for those of us who live and breathe this setting on a daily basis, facing these complex challenges is part of our everyday routine.

I’m about to complete 30 years working in the Rio de Janeiro prison system, and I can tell you that, despite the complexity of certain issues within this universe of challenges, there is no aspect that is unfamiliar to us. We are able to identify the roots of problems and, if not eliminate them completely, at least minimise their negative impact.

We have been able to approach each issue with discernment, understanding and, most importantly, with a sense of belonging that allows us to effectively manage the secretariat and its challenges.

How is the Prison Administration approaching the social reintegration, education and vocational training of individuals deprived of their liberty?

MRN: We believe that the main challenge is to consider the prison system as a whole, always from the perspective of the social reintegration of those deprived of their liberty, so that they can provide for themselves and their families once they return to society. Without this perspective of intimate reform and education, the prison experience does not fulfil its transformative potential, for either the individual or their family. It is essential that the state provides the basic elements needed for this transformation, offering educational opportunities, such as access to primary and secondary education, and training.

The public, often decontextualised about the reality of the prison setting, assumes that an individual imprisoned for committing a crime should be permanently excluded from society. It is crucial to understand that this is a phase and that without due attention to social reintegration, society ends up receiving back individuals having no improvement in their behaviour or mindset. Our prisons include spaces dedicated to education, but it is vital to expand the offering of technical vocational courses to include wait staff, electricians, carpentry and computing. Participation in these programmes is optional, but for those who choose to get involved, the state must be ready to support those seeking to qualify and work during their imprisonment.

We are currently focusing on creating a prison unit that will encompass both technical and vocational training and basic education for individuals deprived of their liberty. This project, which is being implemented in the Esmeraldino Bandeira unit, aims to attract partnerships from the business and commercial sectors, who are interested in investing in prison labour. These initiatives seek to integrate industry within the prison units themselves, as has been done in other states, where proximity to factories facilitates business partnerships.

Currently, we are promoting workshops for entrepreneurs, highlighting the cost-benefit relationship of using prison labour for everyone involved: the entrepreneur, the inmate and the prison management. This cooperation not only benefits the businesses economically but also promotes the inmate’s self-esteem and rehabilitation, highlighting the importance of education, professional qualifications and work.

JT: Working in conjunction with the electronic monitoring of aggressors, the “panic button” was implemented to support the protection of women victims of aggression.

What does this tool consist of, how is it being used and what impact has it had so far?

MRN: The “panic button” is a tool implemented to strengthen the protection of female victims of violence, working in synergy with the electronic monitoring of aggressors, and providing rapid and coordinated action to protect victims.

When triggered by the victim, who carries the device in her handbag, a real-time alert is sent to the monitoring system. This automatically triggers the nearest police vehicle to respond to the call, ensuring an immediate response. Thus far, there have been no negative events reported in Rio de Janeiro.

This is a complementary tool to the electronic monitoring of aggressors through anklets, under continuous surveillance and the possibility of early intervention, even before the button is pressed, if dangerous proximity is identified between aggressor and victim.

Currently, Rio de Janeiro has about 134 aggressors being monitored by electronic anklets, of which 75 women have chosen to use the panic button. There has been a significant increase in adherence to the system, from just over 20 users last year.

How is the prison administration addressing the issue of illicit communications in prisons? And specifically, what measures and/or technologies are being used to prevent members of criminal gangs from continuing their activities from prison?

MRN: The prison administration is tackling the challenge of illicit communications within prison units in a very direct and serious way.

Since we took over, one of the main problems has been the entry of illicit devices, facilitated by the large number of people who enter the units every day, including family members, service providers, health professionals, educators and lawyers, as well as individuals throwing devices over prison walls.

Within our system, which includes approximately 50 prison units, we tackle this issue by intensifying searches by prison officers, who are tireless in their efforts, and with the work of our sniffer dogs. In 2023 alone, we managed to seize 10,000 mobile phones inside our prisons.

We also carry out special operations in conjunction with SENAPPEN, such as Operation Mute, which takes place in integration with other states, and also specific state operations, such as Chamada Encerrada (Closed Call) in the state of Rio de Janeiro. In the last operation, carried out at the beginning of 2024, for example, we managed to remove 99 mobile phones in a single day from all prison units.

We are currently implementing a tendering process for the acquisition of mobile phone network jammers. We hope that over the next six months, we will be able to begin blocking ten of the most sensitive prison units in Rio de Janeiro, marking a significant advance in the control of illicit communications and the prevention of criminal activity inside prisons.

Maria Rosa Nebel

Secretary of the Penitentiary Administration, Rio de de Janeiro, Brazil

Maria Rosa Lo Duca Nebel is a Penal Police officer who has been a career-long civil servant for 29 years. She has a bachelor’s degree in legal sciences and a postgraduate degree in Project Management. Among other positions, Maria Rosa was Director of the Cândido Mendes Penal Institute and Director of Production and Marketing at the Santa Cabrini Foundation, the organisation responsible for managing prison work in the state of Rio de Janeiro. It was here where she consolidated her vision of education, training and work as the path to resocialisation.

Advertisement