Interview

Ina Eliasen

Director-General, Department of Prisons and Probation, Denmark

What are the main challenges facing the Danish prison system, and how are you addressing them?

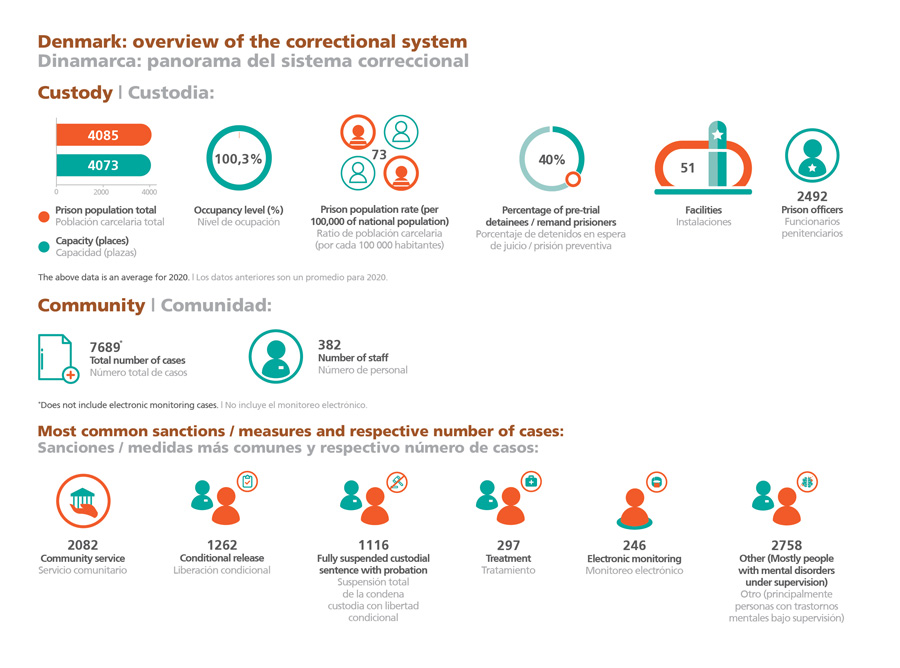

IE: In fact, we have a very critical situation in Denmark, due to severe overcrowding problems and a shortage of staff. We need almost 200-300 more prison officers than we have now, and our occupancy level exceeds 100%. To address the prison overcrowding issue, we are building new infrastructure capacity; in recent years, we have built almost 600 prison cells, and we will create another 300 cells in the coming years. However, this means that the staff shortage will be even more serious than now. On the other hand, we are trying to recruit as many prison officers as possible, and we are trying to keep the prison staff we have by improving the work environment.

What are the main issues regarding staff, and what has been your strategy to tackle difficulties at this level?

IE: We face challenges similar to many other correctional systems across Europe and elsewhere regarding the recruitment and retention of prison staff. It is challenging to recruit and maintain prison staff. To reverse this, we have implemented a one-year strategy with an extremely narrow focus.

This is not how we usually develop and implement strategies, because under more normal circumstances we want most of our tasks to be part of a concerted strategy. In this case, we got all employer groups to accept the premise that we should focus primarily on recruiting prison officers.

Hence, we launched a new concerted recruitment campaign where we created a digital universe with gaming features, where potential new officers – and the public in Denmark as well – are shown situations and dilemmas of a prison officer’s work life. The feedback we have received on this campaign has been very positive because it shows how difficult it is to work as a prison officer, the countless dilemmas they face every day, and the need to make decisions quickly. In general, I think society’s perception is that it is easy to be a prison officer, but it certainly is not.

The recruitment process is tough because we have very high standards for joining the prison system. In fact, we select only a fifth of those who apply. We want to have even more people applying to be prison officers, but we already have many applying every year. For us, high standards are fundamental, as the job of a prison officer is a highly skilled profession.

Concerning staff retention, we are focused on improving the work environment, especially in prisons. Although we have been working on this for years, we recently tried a new approach by involving the entire organisation: we asked prison and probation staff to suggest concrete ideas on how to make The Prisons and Probation Service a better place to work and how to develop our organisation.

When I started this internal campaign to find new solutions and new working methods, I was a little apprehensive because I didn’t know what kind of suggestions I would receive from prison staff. I have however been very impressed and pleased with the level of engagement among the prison staff and the rest of the organisation, and I have received many professional and viable recommendations on how to improve the work environment. For example, requests for removing administrative and security procedures that are excessive or no longer make sense.

Many of the employees told me that such an initiative would really make a positive impact in their daily work. Another suggestion is, for example, changes in the planning of their work schedule that makes it easier for them to plan ahead. These are concrete suggestions that we have managed to implement quickly. In fact, we have received over one hundred specific recommendations and have already implemented several of them.

This participatory approach has already resulted in improvements in team morale and the organisation’s social climate. I realise this when I visit institutions and receive emails from prison staff telling me that the changes we have implemented give them hope for an improved work environment and a climate of change. Also, the changes make employees want to invest energy and time in developing the organisation. It may sound easy, but it really commits leaders to either initiate the changes that are being proposed or come up with a good explanation as to why they are not being introduced.

Our long-term strategy includes continuing to improve the training of prison officers. Currently, this training is given over three years and students shift between internships and the school-bench to give them both theoretical knowledge and practical experience. Our agency provides training for prison officers, and the admitted candidates must meet several strict requirements, including strong social skills, the ability to cooperate and more concrete criteria such as being 21 years of age, having a minimum level of education and a clean criminal record. In addition, we also focus a lot on oral and written expression skills because this is a crucial part of the job. By strengthening the training of prison officers, I think we are going to move the organisation in the right direction.

(...) we are trying to recruit as many prison officers as possible, and we are trying to keep the prison staff we have by improving the work environment.

What is your leadership style, and what role does it play in these and other challenges facing the agency?

IE: My leadership style is open and very much based on dialogue. This approach also allowed me to involve the entire organisation in its own development. This is very important because we are in a very critical situation. We needed to approach the staff and the organisation in a new way. I firmly believe that part of the solution to our problems is to involve our entire organisation, but at the same time set a very clear direction to where we are going.

What is the level of technological development in prisons and probation in Denmark, both at the operational level and for the benefit of inmates and offenders under supervision?

IE: Euphemistically, I would say that we have room for improvement. Denmark is one of the most digitised societies globally, which means that it is very difficult to follow the normal development of society outside the prison walls, because we have all those requirements and security measures when it comes to implementing new technological solutions.

Nevertheless, we have, for example, Internet-based education in some of our prisons. I think this is crucial because when you have a digital society, as we do, and when you have the responsibility to rehabilitate inmates, you have to ensure that they are ready for life beyond the prison walls.

And this means that we have a tremendous responsibility in this area too, but it is challenging to keep up with the development of society in general due to the costly heavy security requirements of prisons.

What are the main challenges and achievements in the probation area?

IE: Probation is a very different reality, where we have no overcrowding problems, and neither do we have staff shortage issues. It is effortless for us to recruit staff for probation in our organisation.

We have 4,200 inmates while we have 10,000 people on probation. We have a tradition in Denmark of using probation and electronic monitoring measures, so this is a significant part of our Department. In the future, it will be interesting to follow the technological development in the field, as it offers a number of opportunities in this particular area.

By strengthening the training of prison officers, I think we are going to move the organisation in the right direction.

The Covid-19 pandemic has brought great challenges to correctional services worldwide. Given the restrictions resulting from the pandemic crisis, what kind of measures have been implemented in Denmark?

IE: In many parts of the world, the Covid-19 pandemic has meant that very drastic steps have been taken in prisons, such as early releases and suspension of sentences, etc. We have not taken such steps in Denmark, but we have focused on preventing the virus from getting into our prisons.

This has meant very limited access to visits and leave.

In the spring of last year, we practically suspended all activities in and around our prisons, both in regards to education, prison work and industries, visits and leaving prisons. We closed for a few months and then went back to normal. During the summer and towards the end of the year, we had no restrictions. However, in the final stretch of 2020, we had to resume the restrictions due to the increasing number of COVID-19 infections in prisons and society in general.

Our approach to managing the pandemic was to examine, twice a week, the restrictions we needed to have in place, assess the number of infected inmates and staff, and whenever it was a number that we could handle, we would remove the restrictions. We have continuously monitored whether the restrictions in the prisons were sufficient and, of course, also whether we could remove restrictions.

In our management of the COVID-19 pandemic in prisons, we managed to find the right balance between restrictions and the health of inmates and prison staff, which is also the conclusion of the Parliamentary Ombudsman after evaluating our efforts. We have just received his report and we are very proud of the reported evaluation. In addition, we did not have any significant outbreaks of COVID-19 in our prisons, so our strategy was very successful.

Despite our prison overcrowding problems, the pandemic has not led us to reduce our prison population with measures such as early leave, conditional release or transferring prisoners into the community, like the measures we have seen in some other countries. However, for a period, during the lockdown, no new convicts were summoned to serve their sentences — this measure allowed us to have rooms for prophylactic isolation or quarantine, if necessary.

As for court hearings, at the peak of the pandemic, in the spring, the courts suspended their work as well, so the situation was easy to manage at that time. However, when the Prison and Probation Service shut down in the winter, the courts continued with their normal activity, so we tried to hold as many videoconference hearings as possible, but we soon had to go back to normal and take our prisoners to the courts.

During the worst months of the pandemic, we also suspended electronic monitoring because, in Denmark, our probation officers usually visit the probationers once or twice a week, and we couldn’t risk spreading the COVID-19 virus through those close contacts.

Ina Eliasen

Director-General, Department of Prisons and Probation, Denmark

Ina Eliasen held various positions in the Danish Department of Prisons and Probation between 2005 and 2017, including Chief Inspector of Copenhagen prisons and Executive Director for the Capital Region, which includes all prison and probation institutions in Copenhagen and the surrounding area, as well as the Faroe Islands. Before taking up her current position, she was the Danish Police HR Director. She is the first woman at the helm of prisons and probation in Denmark, a position she took on in July 2020. She holds a master’s degree in Law from the University of Copenhagen.