// Interview: Francisca Van Dunem

Minister of Justice, Portugal

JT: What are the main challenges facing the Portuguese justice reform process in general and criminal justice in particular, and what are the priority areas for intervention?

FVD: From a chronological perspective, one of the main challenges we had to face was in the field of economic justice. It is a complex segment in which the litigation took on a numerical dimension to which the courts could not respond adequately, due to the economic crisis that the country went through. We have had moments of great congestion of the courts in two fundamental segments: that of executions and that of insolvencies.

When I took office, it was urgent to reduce the pendencies, which were very much pointed out by international bodies as responsible, to some extent, for the weakness of the economic fabric and for the investment in the country being less attractive. And, in fact, we have managed to change that reality. We did a meritorious job, which was reducing the pendency in more than 350 thousand processes. On the other hand, this allowed for an improvement in the response time of the courts.

At the level of civil justice, although the amount of pendencies has been quite small, we are faced with problems of increasing complexity, associated with issues of an economic and economic-financial nature, even as a result of the crisis. The enormous litigation processes that we have, which are related to the banking sector (and that led to State intervention), are highly complex and call for highly technical intervention in areas where the courts do not have their own technical competencies, making them very dependent on consultancies.

With regard to criminal justice, our response is very good in the segments of small- and medium-sized crime: response times are good, crime clearance rates are also good, and the so-called Institutes of Conscience and Opportunity are widely used. Resorting to these Institutes makes it possible, on the one hand, to reach a consensus on responses that favour reparation for victims and, on the other, to use simplified forms. In view of the country’s criminal structure (about 70 per cent of which is small and medium), the use of these formulas, especially by the Public Prosecution Office, has enabled us to obtain very good results.

With regard to serious and organised crime, against property and against individuals, the results are also good, both from the point of view of the crime clearance rates and at the level of the speed of the process and the trial decision.

On the other hand, the economic-financial crime segment is where we find the greatest difficulties, associated with the technical complexity of the matters, which prolongs the resolution of processes. Many are very complex, involve many agents and the reality in question is not always one of simple comprehension for jurists. In this way, technical advice is critical in clearing up this type of crime.

And, here, we still have a challenge that we must continue to face, by inducing improvements that allow for faster responses from the justice system; not only in human resources, which we have reinforced but also in technologies that have seen a large investment. But it is important to review the methods, which include the issues of connecting the processes and forms of consensus that have allowed other countries to establish processes of this nature and complexity more quickly.

We clearly have an excessive prison population. To try to respond to this and other issues, we proceeded to make a legislative alteration (…) At the same time, we increased the accommodation capacity.

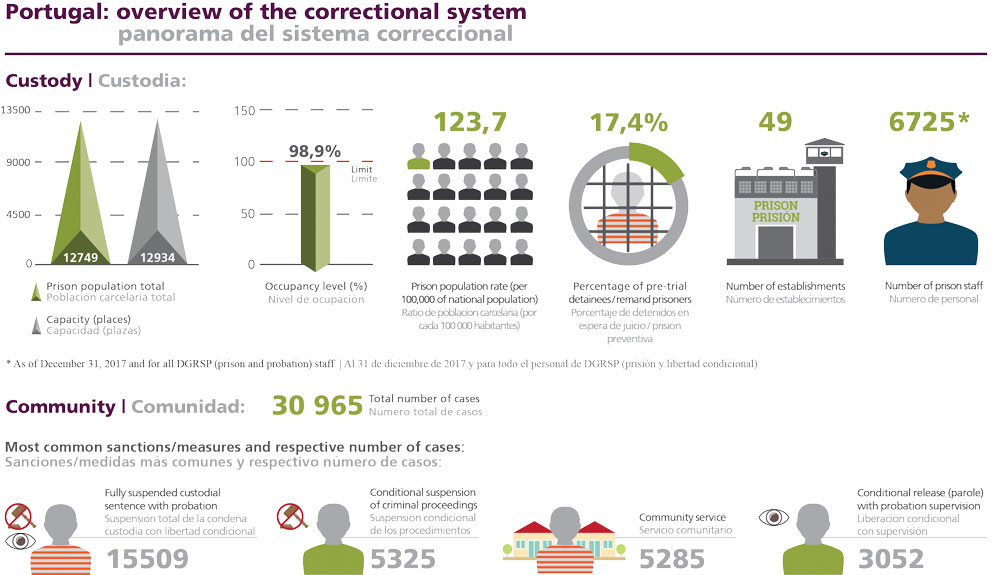

In criminal justice, we also identify a difficulty and that has to do with sentencing: we still have 123 prisoners per 100,000 inhabitants, a rate that is not compatible with either the structure of the crime or the levels of security in the country. Just look at countries like France or Italy that have a ratio of about 102 and 89 respectively. In this matter, there is still work to be done, which will surely involve the judiciaries and the Superior Councils, in the sense of raising awareness for greater adequacy of penalties.

We clearly have an excessive prison population. To try to respond to this and other issues, we proceeded to make a legislative alteration that focused on short sentences. Until then, magistrates could apply “days of imprisonment” and semi-detention to crimes that corresponded to a prison sentence of up to one year. In the case of the former, people generally served their sentences on weekends and it was therefore very difficult to find, for these very short periods, treatment and resocialisation programmes for them. Semi-detention, on the other hand, was a regime that, although provided for in the law, was rarely enforced.

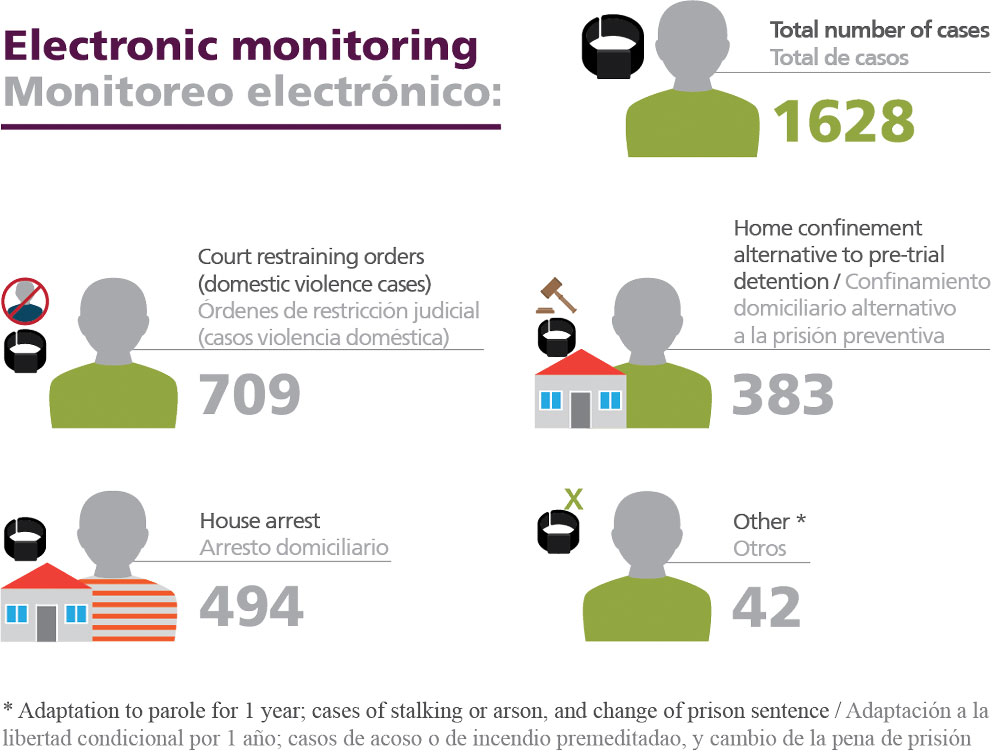

Thus, it was necessary to rethink that imprisonment model as an alternative to prison sentences of continuous short-term: as a regime of compliance with the short prison sentences, we went on to use house arrest with electronic monitoring, hence extending the framework of the baseline prison sentence from one to two years.

The law entered into force in November 2017 and had a great deal of adherence to the judiciary and therefore we achieved, in a very short period of time, a very significant level of implementation. House arrest with electronic monitoring already existed as a substitute sentence, but if between January and October 2017 we had 86 cases, in the following six months we had about 500. We came to the end of 2018 with more than 700 cases, which also explains the reduction in the prison population. Now, we can say that, globally, the prison system is not overcrowded: the capacity is for 12,934 inmates and the system now has 12,749, that is, an occupancy rate of around 98%.

It is not possible to speak about criminal justice and ignore the issue of victims. A small reform of the Commission for the Protection of Victims of Violent Crimes is underway, which, in association with NGOs, will allow for the creation and financing of support and protection responses to some segments of crime victims. At the same time, we are creating conditions so that the Investigation and Criminal Action Departments can be equipped with support offices for victims of gender violence.

A cross-cutting issue throughout the justice system in Portugal is the need for innovation. It is a great challenge and one of the priorities of this mandate. We have organisations dating back to the beginning of the last century, and we need to have 21st-century ones: in prisons and in courts as in the field of records (although in the last century the latter has experienced modernising interventions that other subsystems have not). Thus, we have been working towards introducing innovation, not only in the technological sphere, with the adoption of automation facilitators of work and inducers of greater comfort for citizens, but also at the level of work processes, by reviewing and introducing new methodologies, and streamlining document circulation and flows. Modernisation is one of the big brands that we want to leave behind.

At the level of the courts, we have the Tribunal+ Project, within the framework of the Justiça Mais Próxima programme (“A Closer Justice”), which aims to get closer to the citizens. It is composed of a set of components, it started with 120 measures and now has 150; many (more than 70) are already implemented and, in practice, change the way justice is practised in Portugal. More than that, they improve the resources and change the way in which justice practitioners practice it and, as a result, citizens enjoy a friendlier model, more focused on them and with more ability to transmit information and translate it in a simplified way.

JT: What is being done to improve State intervention at the level of enforcement of sentences and measures and social reintegration?

FVD: The report entitled “Looking at the Future to Guide the Present Action” – a piece of work we have carried out and which embodies the Government’s philosophy of action in the field of execution of sentences and measures – includes a Plan covering the prison system, the system of community sentences and measures as well as the educational tutelary system.

On the one hand, we know that the merging of the custodial component with that of social reintegration has, in some way, reduced the latter and, eventually, altered the ecosystem within the system of execution of sentences, where the security dimension has greater importance. It is, therefore, our intention not to lose sight of the purpose and logic of intervening with services responsible for the sentences’ enforcement, which is social reintegration.

Prison security is important, but – besides the reinforcement of human resources – it can even be facilitated, streamlined and improved through new and enhanced surveillance technologies, while social reintegration, even if it uses technological tools, passes very much through individual human contact and through technicians, who are the only ones capable of becoming interlocutors and motivating the behavioural changes of those who are inside the system. The technicians are the ones who, through accompaniment, encourage the offenders to carry out reintegration plans and to find ways of living a dignified and satisfying life once in freedom.

However, we still have the problem of prison infrastructure: we cannot approach reintegration, in the terms in which we intend it if people live in subhuman conditions. Thus, when the conditions of the entire built penitentiary park were lifted, a model of action, a 10-year Plan (2017-2027) was established. Most of the establishments are old and have not had large investments in maintenance, which in some cases is difficult and very expensive. There are also issues related to the location of establishments: for example, in the metropolitan area of Lisbon, the prison response needs to be balanced, including the Sintra line (three establishments) that will undergo a reinforcement, and the south bank of Lisbon, which needs to be redimensioned with the construction of a medium-sized prison. In districts such as Braga, Aveiro and Faro, it is essential to have new, larger and more adequate structures.

Currently, the system has fewer pre-trial detainees (we went from 30% to 16%), which is an advantage and facilitates life inside prisons, but these must offer better infrastructural conditions. Thus, based on the analysis made in that Report, it was concluded that eight penal establishments should be closed, while we decided to open five new ones.

The Plan implementation has resulted in a significant reduction in the prison population in the Lisbon Penitentiary Establishment (EPL), one of the most questioned institutions and suffering from serious problems especially on the lower floors (the ground floors). The EPL had a population of more than 1,000 inmates and at the moment it is home to about 800; in addition, we managed to release the ground floors, which were identified by the Committee of the Council of Europe for the Prevention of Torture as an area with very poor habitability conditions. The goal is to close EPL, while advancing with the construction of modules in some establishments in the Lisbon area, by increasing the capacity and facilitating the process of vacating the EPL. The EPL is one of our priorities. Also, a priority is the Tagus south bank, especially Setúbal, where the prison establishment has very bad conditions.

With the construction of the infrastructure itself, we began with Ponta Delgada (Azores) and the establishment of the southern margin of the capital. At the moment, in Ponta Delgada, the first phase of the construction process has already begun, and in the south bank of the Tagus, the location and the business model have already been established, and the base project is being developed. At the same time, we increased the accommodation capacity in some other establishments and improved the conditions of contact with the families in several others.

At the level of social reintegration, we have strengthened human resources, both for graduate technicians and professional ones, and we have introduced new and more targeted programmes for certain categories of convicts (including for perpetrators of domestic violence and arson crimes).

A cross-cutting issue throughout the justice system in Portugal is the need for innovation.

JT: In the report published in February 2018 following its last visit, the Council of Europe’s Committee for the Prevention of Torture (CPT) urged Portugal to address cases of ill-treatment of prisoners by custodial agents; poor habitability in some establishments; limited opportunities for prisoners to engage in work, educational and intentional activities; and insufficient or inadequate health care. In addition, the report states that at Monsanto High-Security Prison (Lisbon) nothing had changed since the CPT’s visit in 2013, with the vast majority of prisoners confined to their cells for up to 22 hours a day.

What improvements were implemented in the dimensions identified by the CPT?

FVD: The recommendations of the CPT were and are being complied with. The CPT refers to situations associated with violence against prisoners. Regarding ill-treatment, and at the preventive level, we have reinforced training about human rights in the last admission course to the body of the prison guard. Last year, in cooperation with the Secretary of State for Equality, sensitisation actions were carried out regarding migration, interculturality and non-discrimination matters. These have involved 342 staff members, including prison officers and social reintegration technicians. Such training and awareness initiatives are ongoing.

In addition, we have the repressive dimension: when we become aware of an aggression on an inmate or of a violation of his or her rights, an investigation is obviously set up which may result in disciplinary consequences for those responsible for the act.

The bad habitability conditions in some prisons are identified and we have acted on them not only in the terms that I have already mentioned – that are part of the Plan implementation – but also through work in several establishments.

The training offer entails a varied set of skills and an important diversification effort has been made, for example, the training of forest sappers that began last year.

Prison work aspires to cover the widest possible universe of prisoners; they produce from agricultural products to Arraiolos carpets, to furniture, to components for electronic equipment. But there is still room for improvement, both in prison training and work.

Health was an area in which we invested a lot and in which we had the support of the Ministry of Health. In addition to having created conditions for the practice of telemedicine in penitentiary centres, we proceeded to dematerialise the clinical files – the doctor in the hospital or in the prison establishment manages to access the clinical file of each inmate, which facilitates the knowledge of their historical and therapeutic accompaniment. Paperless medical prescriptions are also issued; the doctors already have access to the Electronic Medical Prescription across all the country’s prison establishments.

In addition, we have a set of protocols with the Ministry of Health that define referral procedures (all inmates with infectious diseases have a referral hospital) and, preferably, doctors go to the prison for the appointments. Blood sampling and some diagnostic tests can also be carried out in the prison centres. All this affects a significant part of the prison population and, above all, has a positive impact on those who are weakest and in need of health support.

We also improved sustainability from the point of view of health workers, as the outsourcing model on which the system was based turned out to be inadequate. Hence, our strategy was based on gaining greater autonomy, so we internalised many resources, including doctors and nurses.

A Diploma to address mental health issues is also underway at the moment. The law provides for the regulation of the model of containment of persons to whom security measures are applied by virtue of psychiatric problems that have determined the practice of the crime. As there was no implementation of that rule we are now specifying it in a model in which, preferably, people comply with security measures in a hospital establishment.

The issue raised by the CPT in relation to the high-security prison establishment of Monsanto has basically to do with the time spent in the cells. The situation was altered, obviously preserving the security requirements.

JT: In August 2017, an amendment to the Penal Code came into force, which is the first amendment to the Law regulating the use of electronic monitoring. What results were verified and are expected to occur in the system?

FVD: There was an increase in the use of house arrest sentences with electronic monitoring, which had a great impact on the decongestion of the penitentiary system. And we hope that this continues. That is what makes sense and is logical, bearing in mind the structure of crime in Portugal.

But obviously, decongesting prisons is not enough. Those serving sentences at home are also part of the system, and we have to take care of them as well as those within the walls. Although people who are at home with electronic monitoring can go out to practice other activities, obviously supervised, those who are at home and permanently shut inside without any other activity, obviously experience great stress. The penalties have a resocialising function that must be fulfilled in any circumstance, which implies an increase in the number of social reinsertion technicians who follow up on these home inmates and reinforce the electronic monitoring teams.

There was an increase in the use of house arrest sentences with electronic monitoring, which had a great impact on the decongestion of the penitentiary system.

JT: Are there other measures for the decongestion and rationalisation of the penitentiary system or was that the main one?

FVD: From the normative point of view this was the main measure. We do not intend to legislate more on the execution of sentences until the end of the legislature, but rather to improve it, to have better and better conditions for the application of criminal execution in the community, and to accompany and motivate sentencing on this matter. For the time being, we do not envisage any one-off measures of general decongestion. We must focus on measures that improve the quality of life in prisons.

[International events like the Conference Technology in Corrections] are very important (…) they help us walk with our partners and find solutions that we have not considered, do not know of, or that we would never have anticipated before.

JT: In April 2019, Portugal (the Directorate General for Rehabilitation and Correctional Services) will host the conference “Technology in Correctional Services: Digital Transformation”, organised by ICPA – International Association of Correctional Services and Prisons and by EUROPRIS – European Prison and Correctional Services Organisation.

What role can technologies play in improving prison systems and what is the importance of this – and other international events – for the Ministry of Justice and for the Portuguese Penitentiary and Rehabilitation Services?

FVD: These events are very important, insofar as they promote information, knowledge, the sharing of experiences and good practices. They help us walk with our partners and even find solutions that we have not considered, do not know of, or that we would never have anticipated before. It is important that Portugal participates and welcomes such occasions, as welcoming them is a sign of openness and interest in sharing efforts with other countries and with other entities participating in the same objective: improving the penitentiary system and conditional release.

Technology plays an important role in the prison setting, certainly in terms of security, for example through the electronic monitoring of spaces, as well as in the processes of controlling the entry and exit of system agents, visitors and inmates.

Technology is also fundamental in the training of prisoners, in the level of work and health. Especially at the level of training, there are many viable programmes through technologies, specifically, electronic content. But technologies are also important for the maintenance of prisoner contacts with the respective families, with the possibility of communicating by videoconference, for example.

Contact with the courts is also facilitated by technology, as inmates can participate via videoconference in court hearings when they are witnesses in a trial, provided the court allows it.

Moreover, at the level of the prison management system: the files of the inmates are in electronic format so that they have a virtual space – to which they have access – where all the information concerning them is gathered. They can even establish interlocution with the management – it is a project that we have for some establishments: they are the so-called inmates’ kiosks.

New technologies can become precious work tools even in the intervention and monitoring of sentences and protective educational measures that are carried out in the community.

//

Francisca Van Dunem holds a degree in Law and has been a Public Prosecutor since 1979. Throughout her career she has held various positions, including Delegate of the Office of the Prosecutor of the Republic in several Courts, Member of the Office of the Prosecutor General (1999 -2001), Director of the Criminal Investigation and Action Department of Lisbon (2001-2007) and District Attorney General of Lisbon, since February 2007. She was a member of the European Judicial Network in Criminal Matters (2003-2007) and member of the Criminal Procedure Code Revision Committee, in 2009. She was also a member of the Superior Council of the Public Prosecutor’s Office.