Article

Kavan Applegate & Helena Pombares

The design and infrastructure of prisons and the impact on incarcerated people, staff, and visitors, have long been subjects of conversation, debate and reform. As society advances, and the body of evidence-based research expands, so too does our understanding of the impact that prison environments have on incarcerated people. The salutogenic design concept provides a theoretical framework for a ‘psychosocially supportive design’, which promotes health and well-being for the users of a space. In the case of prisons, it aims to engage the users mentally and socially, incorporating access to attractive spaces for social interactions allowing positive experiences in that environment, and facilitating social reintegration.

This article explores the psychological effects of improved environments, current advancements in international prison design, the opportunities presented by contemporary infrastructure, and the importance of salutogenic design and biophilia in therapeutic prison design. Additionally, we will further explore how prison conditions influence rehabilitation outcomes.

Salutogenic Theory: The psychological impact of better environments on incarcerated people

The environment in which incarcerated people are housed plays a crucial role in their psychological well-being (Moran, 2023). Mental health issues are prevalent in custodial institutions, with prisons being the public spaces that have the highest number of individuals affected, second only to mental hospitals. The prevalence and severity of these issues can vary based on factors such as age, gender, and ethnicity. Therefore, it is essential to enhance the design of these built environments to prevent the worsening of any existing mental health problems among incarcerated people.

Significant evidence shows that traditional prison designs, characterised by stark, oppressive conditions, exacerbate feelings of isolation, anxiety, and depression among incarcerated people. In contrast, prisons that are considered ‘good’, and even models to be followed have better-designed environments having at the forefront human well-being and can significantly improve mental health outcomes – and enable the optimal implementation of the prison operating model.

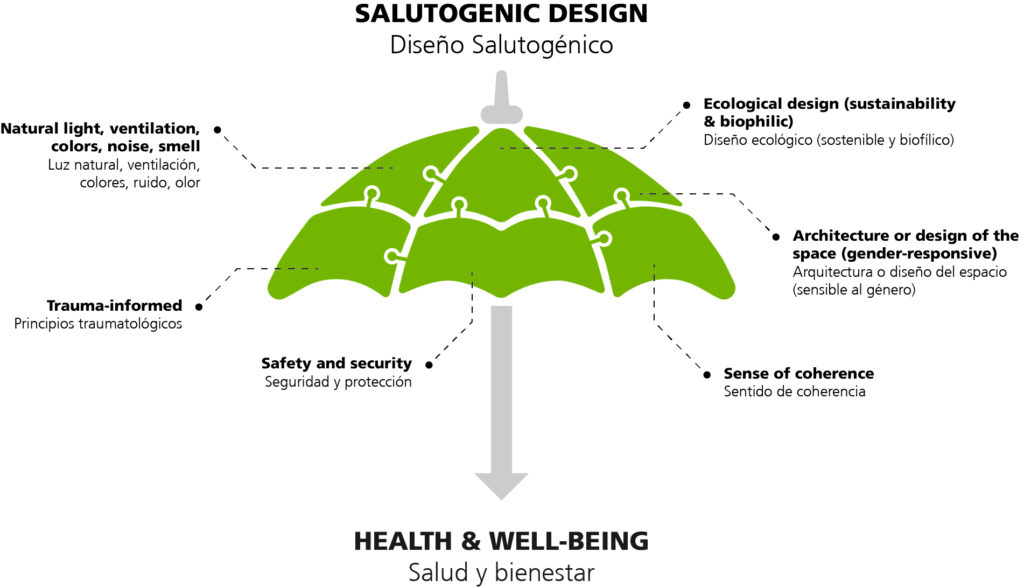

Salutogenic design can be explained as an umbrella term covering several essential approaches, methods and theories that together lead to the health and wellbeing of all users of the space. It has a human-centred supportive design and in prison environments it will, therefore, reduce the risk of exacerbating any existing mental health issues incarcerated people will bring with them, as well as reducing the likelihood of new mental health issues emerging.

Research has shown that access to natural light, outdoor spaces, and being in contact or just having sight to nature can reduce stress and promote physical and psychological wellbeing, which in turn will be translated into higher levels of rehabilitation and consequently lower levels of recidivism among incarcerated individuals (Gillis, 2015).

Nature offers a well-balanced mix of colours, forms and scents which stimulates human psychological wellbeing. Furthermore, studies on the effect of nature in prisons argue that people who have a visual sight of nature have fewer health issues than those who do not.

Biophilia

The concept that humans have an innate need to connect with nature for their fulfillment and well-being is known as the “biophilia hypothesis.” This term was first introduced by Edward Wilson in his 1984 book, Biophilia (Wilson, 1984). Biophilic design is a strategy used to bring nature closer to people, and has been applied at both building and city scales to enhance personal and environmental health since the 1960s. Prominent architects such as Le Corbusier, considered the father of modern architecture, have utilized this concept in their work (Le Corbusier, 1967;1982).

“Exposure to the natural world is essential for human wellbeing because humans have an innate connection with the natural world (Gillis, 2015).”

Exposure to nature has been found to have positive responses on human psychology and physiology in contribution to improved health and wellbeing (Söderlund, 2019). Biophilic philosophy encourages the use of natural systems and processes in design to allow for exposure to nature. Biophilic principles have further been incorporated into environmental psychology theories of Attention Restoration Theory and Stress Recovery Theory.

Both theories suggest that there are stressful and non-stressful environments, and that non-stressful environments can actively help people recover from stress and fatigue (Gillis and Gatersleben, 2015). The theories are supported by studies that have found that exposure to nature reduces heart rate variability and pulse rates, decreases blood pressure, lowers cortisol and increases parasympathetic nervous system activity, while lowering sympathetic nervous system activity (Söderlund, 2019).

Biophilia is not merely about providing trees and greenery, but a multitude of various factors which can be divided into direct experience of nature (light, air, weather), indirect experience of nature (natural materials, evoking nature) and the experience of space and place (prospect and refuge, organised complexity).

Professor Dominique Moran led several studies on how environmental characteristics like vegetation around a prison building can affect the behaviour of building occupants. The findings of these studies are that high levels of green vegetation are related to lower levels of self-harm and violence among incarcerated people. For instance, prisons that incorporate green spaces and gardens provide opportunities for physical activity and relaxation, which can alleviate symptoms of depression and anxiety.

A key element of designing with rehabilitation and well-being at the forefront is to create therapeutic spaces and calm environments where people feel safe and secure. Biophilic design elements often incorporate provision of access to natural light and fresh air, views to the landscape, and use of colour and natural materials to invoke a sense of calm in the built environment.

Further biophilic design elements may feature artificial lighting that mimics natural light and circadian rhythms, sound installation of nature sounds, the implementation of green spaces either by using real trees and plants or images of green spaces indoors when planting trees and other greeneries is not possible due to security reasons, lack of space, and adding/adapting green spaces outside (Partonen and Lönnqvist, 2000).

Best practice prison design utilises biophilia to aid rehabilitation in many ways, including:

- Internally – through the use of murals and scenery on walls, natural textures and materials, internal planting, water and nature sounds and at times small water features. Borrowed landscape – where spaces cannot access nature, views to greenery and nature from windows and access ways.

- Externally – allowing incarcerated individuals to get their feet on the ground and be amongst the landscape itself.

Smaller scale

Much has been discussed about the increase in global incarceration rates, particularly since the 1970s and 1980s. To accommodate these significant incarcerated populations, not only have more prisons been constructed, but also sizes of individual prisons have been increasing leading to heightened institutionalisation, and reduction in the personalisation of individual space.

More recently, some jurisdictions have begun to replace large, overcrowded prisons with smaller, more manageable institutions. These smaller facilities can be located closer to the communities from which incarcerated people come. This proximity allows for greater family involvement and support, which is crucial for successful reintegration. Moreover, community-based designs often include partnerships with local organisations to provide resources and support for incarcerated people.

As evidence shows that environments that promote social interaction and community engagement can help incarcerated people develop positive relationships and reduce feelings of oneliness, design approaches for prisons with large populations can attempt to address this through creating smaller communities within the larger populations. This may be achieved by incorporating smaller individual accommodation wing sizes, smaller groupings of buildings and the layout of buildings across a campus to create discrete zones.

Advancements in technology and construction

The last 30 years have seen seismic advances in the use of technology within prison environments, and more recently these advancements have shown to move beyond additional security overlays and to provide some prison operators with technology-based solutions that thereby allow more therapeutic installations to be incorporated.

These developments include:

- Incorporation of wall-sized video projections into sensory rooms with audio support that allows internalised spaces to be transformed into immersive natural environments, customised to the needs of the incarcerated person at the time. The addition of forest-sounds (including birdlife) to woodland video, for example, or the sounds of waves crashing to a beach scene significantly elevate the sensory experience.

- Increased use of camera technology and analytics to supplement the increased installation of trees within the secure environment and eliminate any blind spots.

- Secure openable windows (connected to a building management system ventilation override) to allow fresh air and (in the appropriate climate) reduce reliance on air-conditioning and thus reduce energy consumption.

- Using vital-signs contactless monitoring technology within cellular environments to constantly track the physiological wellbeing of at-risk individuals, which provides health and custodial staff with additional data to provide interventions at the optimal times.

- Providing incarcerated persons with in-cell tablet-based video visits for ongoing connection with family and friends, and thus reducing the personal impact on family members for both travelling to the prison and undergoing security screening for a relatively short in-person visit.

- Increased confidence in contraband detection at personnel and goods delivery screening points.

Retrofitting

In the writers’ experience, it is often more common for significant advancements in the implementation of salutogenic and biophilic solutions within new facilities and major redevelopments than within existing prison building stock. This is often caused by government funding streams being aligned with new building opportunities and acknowledged complexities of upgrading occupied facilities.

With the significant amount of existing prison building stock across each jurisdiction, progressive operators are finding methods of enhancing salutogenic environments at comparatively low costs, and often with incarcerated people participating in the design and/or construction outcomes.

In many cases this is achieved by the application of biophilic approaches, such as creating therapeutic and recreational spaces, installing internal planting and introducing gardens and water features in the exterior of the building, enlarging windows for better light and ventilation and updating spaces by painting with more engaging colours and sceneries, using normalised furniture and softer flooring. These features are being shown to contribute significantly to the physiological and psychological well-being of incarcerated people, staff and visitors.

Conclusion

The evolution of prison environments reflects a growing recognition of the importance of humane and rehabilitative conditions. By prioritising a psychosocially supportive design to promote health and well-being of incarcerated people, staff and visitors, leveraging new technologies, and implementing sustainable practices, prisons can create environments that support rehabilitation and reduce recidivism. As society continues to advance, it is essential to ensure that prison environments evolve in ways that promote the dignity and potential of every individual.

References

Gillis, K., & Gatersleben, B. (2015). A Review of Psychological Literature on the Health and Wellbeing Benefits of Biophilic Design. Buildings, 5, 948-963.

Le Corbusier (1967). The Radiant City. New York: Orion Press.

Le Corbusier (1982). The City of Tomorrow and Its Planning. New York: Dover.

Moran, D, Jordaan, J & Jones, P (2023), ‘Green space in prison improves wellbeing irrespective of prison/er characteristics, with particularly beneficial effects for younger and unsentenced prisoners, and in overcrowded prisons‘, European Journal of Criminology.

Partonen, T. & Lönnqvist, J., (2000). Bright light improves vitality and alleviates distress in healthy people. Journal of Affective disorders, 57(1-3), 55–61.

Söderlund, J. (2019). Biophilic Design: The Stories of the Pioneers of the Social Movement. In: The Emergence of Biophilic Design. Cities and Nature. Springer, Cham.

Wilson, E., (1984). Biophilia. Cambridge, Harvard University Press.

Read the point of view of experts and decision-makers.

Kavan Applegate is an architect specialising in the design of secure facilities, driven by a passion for harnessing the transformative effects of architecture to help people live better lives. Over the last 25 years, Kavan has had the privilege of designing many of Australia’s most innovative and iconic justice and correctional projects, as well as works in numerous other secure facilities. As a Director of Guymer Bailey Architects, Kavan co-leads our exceptional architecture, landscape architecture and interior design team across our Melbourne and Brisbane Studios and overseeing our large-scale correctional projects company-wide.

Helena Pombares is an architect and urban planner, criminologist, researcher and a university lecturer teaching for the criminology degrees (and paths) in the UK. She also possesses a masters’ degree in Prisons Architecture and is on the final steps of her journey of a Professional Doctorate degree at University of West London (UWL), researching “Salutogenic Architecture – Reshaping Prison Design for the 21st Century”. Helena has more than 18 years experience in justice architecture and her research on salutogenic architecture of carceral spaces feeds her passion on the effects the built environment has on the users of the space (staff and inmates). She uses evidence found in research to inform the practice to positively impact society.