Blog Article

The freedom of movement is one of the cornerstone principles of the European Union. Enshrined in Article 21(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (European Union, 2012) and Article 45 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (European Union, 2012). It is further established in recital 1 of Directive 2004/38/EC (European Parliament & Council of the European Union, 2004), that “citizenship of the Union confers on every citizen of the Union a primary and individual right to move and reside freely within the territory of the Member States (…)”.

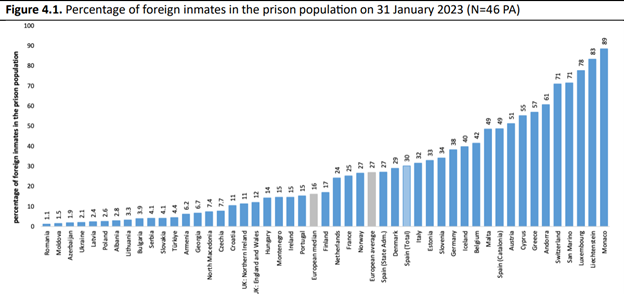

While this fundamental right has brought undeniable benefits for EU citizens, it has also created new challenges for criminal justice systems. As the number of citizens travelling and living across Member States increases, so does the possibility that some of these may be involved in criminal procedures and, as such, of being sentenced in a State that is not their country of nationality or their place of permanent residence. As related in the key findings of the SPACE I survey (Aebi & Cocco, 2024), the average percentage of foreigners in European prisons was 27% on 31 January 2023.

As shown in the figure above, the percentage of foreign prisoners is generally below 5% in Eastern European countries, while in Central and Western Europe it usually exceeds 10%. In nine countries, it ranges from 50% to as high as 89%. According to the key findings of the SPACE reports (Aebi et al., 2024), in 2023 the median percentage of nationals on probation was 88%, while foreign citizens accounted for a median of 12%. In comparison, the European median percentage of foreign prisoners across Europe is 16%. Across all jurisdictions, the proportion of foreign prisoners is consistently higher, often at least twice as high, than that of foreign probationers.

This gap is partly explained, according to Aebi et al. (2024) by the fact that, as it is shown, foreign citizens often face greater obstacles than nationals in fulfilling the requirements for probation, including stable addresses and lack of familial, social and economic ties. Additionally, in several cases foreign prisoners are also given deportation orders after fulfilling their prison sentence, meaning that they would not have the possibility of being placed on probation in that country.

Furthermore, foreign suspects and accused individuals are more likely to be placed in pre-trial detention (Wermink et al., 2022) and less likely to benefit from supervision or alternative measures. This happens despite the general principle that imprisonment – including pre-trial detention – should be used only as a last resort (ultima ratio), as was highlighted in the European Council Conclusions on alternative measures to detention (Council of the European Union, 2019).

EU pathways: advances and challenges

Accordingly, in the EU, steps have been taken to promote the use of alternative measures and alternative sanctions, becoming a key component of the EU’s justice policy, notably in the Hague Programme (Council of the European Union, 2004) and in the Stockholm Programme (Council of the European Union, 2009). The report on prison systems and conditions (European Parliament, 2017) emphasizes their contribution to a more effective management of the prison system, while the aforementioned Council Conclusions on Alternative Measures to Detention (2019), explicitly state in recital 8 that “alternative measures to detention should (…) be considered throughout the whole criminal justice chain”. It further notes that such measures should be applied whenever appropriate to the circumstances of each case, as they can be advantageous to the individual’s reintegration prospects and therefore for reducing reoffending and promoting public security, as asserted in recital 5. Finally, the Commission Green Papen on the application of EU criminal justice legislation in the field of detention (2011), underscores the role that promoting alternative measures can play in enhancing judicial cooperation between Member States.

At the legal level, the EU adopted two key instruments, as a concrete step towards meeting these policy level objectives – Framework Decision 2008/947/JHA (Council of the European Union, 2008), on probation measures and alternative sanctions and Framework Decision 2009/829/JHA (Council of the European Union, 2009), on supervision measures as an alternative to pre-trial detention.

These instruments were designed to support the use of non-custodial measures, to enhance the rehabilitation prospects of individuals across borders and strengthen mutual trust between Member States. Noting the disparities between the use probation or supervision measures between nationals and non-nationals in the EU (Martufi & Peristeridou, 2022), recital 5 of Framework Decision 2009/829 (Council of the European Union, 2009) noted that “it is necessary to take action to ensure that a person subject to criminal proceedings who is not resident in the trial state is not treated any differently from a person subject to criminal proceedings who is so resident”.

However, the application of these Framework Decisions remains very limited (Council of the European Union, 2019; Tudela, et al., 2020; General Secretariat of the Council, 2023). The main reasons identified include a lack of awareness, knowledge and practical experience among practitioners, as well as unclear or complex procedures and a fragmented approach between Member States (PONT Project, 2020; Tudela, et al., 2020). This fragmentation, as Montaldo (2020) underlines “entails that some (even important) domestic measures and sanctions might not have comparable rules in another Member State and could then be hardly adapted (Art. 9) and, in the end, recognised”.

While the transposition of these Framework Decisions into national jurisdictions is intended to provide competent authorities with a reliable basis for cross-border implementation (European Commission, 2014), in practice, this does not always happen. Despite the legal framework in place, judicial authorities often remain hesitant, as doubts persist regarding the proper execution and monitoring of sanctions or supervision measures in the Executing State. At times, major differences can occur between national jurisdictions regarding the nature and duration of certain measures, and in some Member States, these measures may not exist in the criminal system at all (General Secretariat of the Council, 2023). These barriers also contribute to the persistent underuse of such alternatives and the overuse of detention for foreign individuals.

The effective implementation of these Framework Decisions requires the engagement of the entire justice system in each jurisdiction, including competent authorities and probation services. This effectiveness is rooted in the principle of mutual recognition, which relies on trust and cooperation between Member States. But more importantly, such trust and involvement depend on all practitioners – judges, prosecutors, lawyers, and probation officers – having the understanding and clarity about transfer procedures or, at least, the means to attain it.

The role of probation officers and services

A closer look should be given into the role of probation officers, their specific responsibilities and contributions to these procedures. Probation officers may contribute to the application of the Framework Decisions as their assessment, reports and recommendations may hold considerable value in decision making processes.

In Portugal, for instance, probation services prepare reports assessing the suitability of alternative measures or the necessity of pre-trial detention, by order of either a judge, the Public Prosecutor’s Office, or even the offender. In the Netherlands, probation officers are responsible for reporting on pre-trial detention and are also involved in implementing alternative sanctions for adult offenders. In Romania, reforms introduced in 2014 expanded the responsibilities of probation officers, granting them a more active role in case management and in determining appropriate measures based on individual assessments. In France, sentencing and supervision decisions benefit from the input of probation officers and court working groups. Meanwhile, in Belgium, probation officers are required to inform magistrates about the effectiveness of probation measures but often encounter difficulties when supervising individuals who live abroad. In the French speaking community, specific guidelines exist to encourage judicial authorities to implement the Framework Decisions.

In France, Romania, Portugal and Germany, probation officers can play a role at the outset of transfer proceedings involving foreign nationals by preparing assessments for the judicial authorities. When these initial evaluations include recommendations for applying the relevant Framework Decisions, the likelihood of their consideration and eventual application may increase.

However, this process faces a number of challenges. Research carried out in the context of the EMPRO Project shows that their confidence rate, rated on a scale of 1 to 10, is mostly below 5. Based on this data, it is reasonable to conclude that professionals are unlikely to recommend the use of instruments they don’t know how to work with. Clear understanding and strong expertise in these Framework Decisions within probation services are essential and solid knowledge can significantly influence whether and how these instruments are applied in practice.

As noted by the Council of the European Union (2019) and in the final report of the 9th Round of Mutual Evaluations on Mutual Recognition (Council of the European Union, 2023), probation officers represent a key group that would benefit from increased targeted training activities. The later report recommended that efforts be made to raise practitioners’ awareness, develop training programmes with information to simplify these procedures. Moreover, the exchange of practices and experiences among authorities from different Member States can enhance mutual trust in cross-border supervision, which is carried out by probation officers.

In today’s interconnected Europe, initiatives such as the EMPRO project are essential as they will directly address these barriers and professionals’ needs. EMPRO is a European initiative aimed at enhancing the practical implementation of Framework Decisions 2008/947 and 2009/829 across six Member States: France, the Netherlands, Portugal, Romania, Germany, and Belgium.

For this purpose, the project will develop comprehensive training, in order to equip probation officers and services with the tools and skills to promote the implementation of FD 2008/947 and 2009/829. Additionally, the project will take recent developments in the digitalisation of Justice in the European Union and raise and awareness to the benefits of the use of new technologies in a probation setting, as well as to the overall implementation of the two instruments.

EMPRO aims to contribute to a more harmonised and coherent European justice system, one that is more attentive to rehabilitation and human rights, especially for non-national offenders, who are often most affected by inconsistencies in the application of probation and supervision measures.

References

Aebi, M. F. & Cocco, E. (2024). Prisons and Prisoners in Europe 2023: Key Findings of the SPACE I report (Series UNILCRIM 2024/1). Council of Europe and University of Lausanne.

Aebi, M. F., Molnar, L., & Cocco E. (2024). Probation and Prisons in Europe 2023: Key Findings of the SPACE reports (Series UNILCRIM 2024/4). Council of Europe and University of Lausanne.

Council of the European Union. (2005). The Hague Programme: strengthening freedom, security and justice in the European Union.

Council of the European Union. (2008). Council Framework Decision 2008/947/JHA of 27 November 2008 on the application of the principle of mutual recognition to judgments and probation decisions with a view to the supervision of probation measures and alternative sanctions. Official Journal of the European Union, L 337.

Council of the European Union. (2009). Council Framework Decision 2009/829/JHA of 23 October 2009 on the application, between Member States of the European Union, of the principle of mutual recognition to decisions on supervision measures as an alternative to provisional detention. Official Journal of the European Union, L 294.

Council of the European Union. (2009). The Stockholm Programme – An open and secure Europe serving and protecting citizens.

Council of the European Union. (2019). Council conclusions on alternative measures to detention: The use of non-custodial sanctions and measures in the field of criminal justice (2019/C 422/06). Official Journal of the European Union.

Council of the European Union. (2019). The way forward in the field of mutual recognition in criminal matters – Policy debate (JAI 590).

Council of the European Union. (2023). Final report on the 9th round of mutual evaluations on Mutual recognition legal instruments in the field of deprivation or restriction of liberty.

European Commission. (2011). Green paper: Strengthening mutual trust in the European judicial area – A Green Paper on the application of EU criminal justice legislation in the field of detention.

European Parliament & Council of the European Union. (2004). Directive 2004/38/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 on the right of citizens of the Union and their family members to move and reside freely within the territory of the Member States (Citizens’ Rights Directive). Official Journal of the European Union.

European Parliament. (2017). Report on prison systems and conditions (A8-0251/2017).

European Union. (2012). Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (2012/C 326/02). Official Journal of the European Union.

European Union. (2012). Consolidated version of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (2012/C 326/01). Official Journal of the European Union.

Martufi, A., & Peristeridou, C. (2022), Towards an Evidence-Based Approach to Pre-trial Detention in Europe. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, volume 28, 357-365.

Montaldo, S. (2020). The cross-border enforcement of probation measures and alternative sanctions in the EU: The poor application of Framework Decision 2008/947/JHA.

PONT Project. (2020). E-manual for implementing FD 947/2008 and FD 829/2009.

Tudela, E. M. P., Ruiz, C. G., García, L. A., Ríos, B. M., & Alises, G. F. P. (2020). Literature review on the Council Framework Decision 2008/947/JHA of 27 November 2008 and the Council Framework Decision 2009/829/JHA of 23 October 2009.

Wermink, H., Light, M.T. & Krubnik, A.P. (2022). Pretrial Detention and Incarceration Decisions for Foreign Nationals: A Mixed-Methods Approach. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, volume 28, 367–380

Carolina Nogueira holds a bachelor’s degree in Law and a master’s degree in Criminal Law. She has experience in European political affairs at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Portuguese Republic, and in research on prison systems at Lisbon’s Supervisory Court and with Reshape’s Advocacy Team. Carolina works as Consultant and Researcher in the International Judicial Cooperation and Human Rights Portfolio at IPS_Innovative Prison Systems.

João Gomes holds a master’s degree in International Relations, with a post-graduation in Intelligence Management and Security. He has experience in political and diplomatic work, with professional experiences in both internal and external services of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Portuguese Republic. João is the Coordinator for the International Judicial Cooperation & Human Rights portfolio at IPS_Innovative Prison Systems, overseeing the design and implementation of projects related to judicial cooperation in criminal matters in the EU, as well as procedural and fundamental rights in the Union.

This article counted with the contributions of the EMPRO Partnership, including the Ministry of Justice of France, Penal Reform International, the General Administration of the Houses of Justice and the Ministry of Justice of the German Speaking Region of Belgium, the Directorate-General of Reintegration and Prison Services, from Portugal, the National Probation Directorate, from Romania, and the Schleswig-Holstein Association for Social Responsibility in Criminal Justice; Probation and Victim Support, from Germany.