// Interview: Jana Špero

Assistant Minister, Directorate for Prisons and Probation, Ministry of Justice, Croatia

JT: You have moved from the probation sector to be the leader of the prison system as well.

With what spirit have you embraced those bigger roles and responsibilities and what kind of leadership have you adopted? And do you think there are differences in the leadership style needed?

JS: I became the Assistant Minister both for prison and probation in 2017 and it was a post I have assumed with great optimism and full of energy. I had been the Head of the Probation Service for six years, which gave me a lot of knowledge about working with offenders and staff. Sometimes, I say that was like my “pilot project” for the big project that is prisons.

As head of the Probation Service, I was connected to the Prison administration and especially to the international connections about the services that came up. So, I felt that I was ready to take over the prison system as well. I decided that I would bring something new to the prison system, because the probation service was also something new, with a new approach, a very open service as far as thinking and range of possibilities are concerned.

I used to see prisons as something that was very formal, so my leadership approach is actually to relate to the prison governors all the time, to be well aware of what’s going on in our facilities, and to know everything that is needed both for people in prison but also for staff. Furthermore, one of the things I wanted to do was to connect prison and probation services more.

I’m the first female ever to assume this post, in Croatia. Prisons are mostly a men’s world, but I have to say that most of the prison directors are men and they really don’t have a problem with me being a woman. They might have been a little bit surprised when I was appointed but, in the end, business is business and it doesn’t matter if you’re a female or male. The most important thing is having happy prisoners and staff, as well as a safer society; security doesn’t have a gender.

In the probation service, our staff is mostly female, and in that sense, it was a big change. Of course, I had to change a little because the probation service doesn’t work 24 hours, and the offenders are responsible for how they manage their lives albeit being guided and supervised by the probation staff. On the other hand, for the prison service you had to adapt completely to new managerial skills because you are now in charge of everything – housing, electricity, food, medical assistance, etc. – it entails a much broader kind of thinking and action.

Probation Service is mostly about the treatment work, while when you work in prisons the treatment work is just one of the many different aspects that you need to cover and you need to be on top of every aspect including financial, legal, security issues, treatment, health… Everything needs to be there and you have to know a lot about everything.

It’s a huge but rewarding task. Every day you get something that gives you more wind to go further. Leadership depends on the individuals, you must be dedicated, know where you’re going, and you need to be clear on how you’re going to accomplish the agency’s mission.

“We are really proud of our probation system. We have received a lot of compliments from different stakeholders worldwide and it has been recognised as one of the best models on how to develop a Probation Service by the Council of Europe.”

JT: What is the penitentiary situation in Croatia, and what are the main challenges and opportunities facing it?

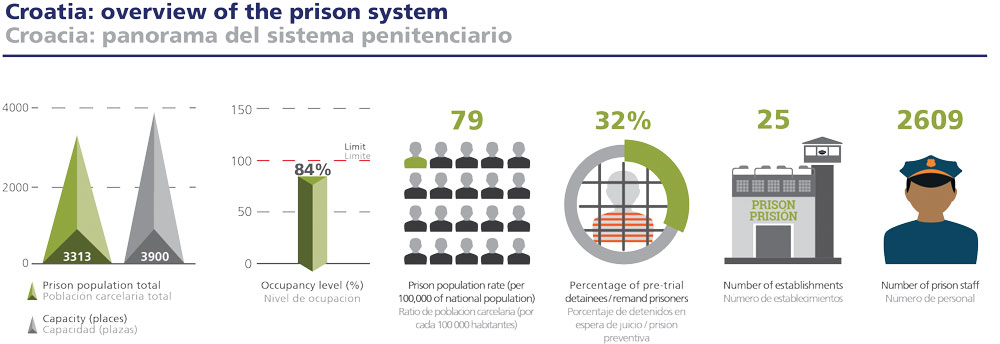

JS: The prison system in Croatia is part of the Ministry of Justice and we have 25 different establishments: 14 prisons and 7 penitentiaries, one of them being a prison hospital, 2 educational centres for juveniles, 1 education centre and 1 diagnostic centre – something I’m very proud of because not many countries have this.

Every prisoner who will serve a sentence longer than six months must go first to the diagnostic centre. There, we have a multidisciplinary team – doctors, psychologists, social workers, lawyers – that works with the offender to assess what would be the most meaningful way of serving the sentence. The team is in charge of preparing a recommendation report regarding the treatment programmes the inmate should receive, which the best facility to serve the sentence would be and so on. Hence, each sentenced person has an equal beginning in the system.

And I would like to clarify the difference between a prison and a penitentiary in Croatia: prisons are for people who serve sentences up to six months and those in pretrial detention. Prisons are usually small in number of beds and they’re usually in the cities, near the court. On the other hand, penitentiaries are for those serving sentences longer than six months; actually, this is where real prison life is going on. Penitentiaries are usually bigger and provide more possibilities as regards work, programmes, and free time.

We have a high number of remand prisoners, around 32% of all our prisoners, but I think we have a good prison system because we used to have an overcrowding problem. Back in 2010, when we were negotiating to become a European Union member state: we had over 5000 prisoners and we only had a capacity for 3000.

After the creation of our Probation Service and the change to the criminal code there was great progress in the reduction of the prison population; today we have a capacity for 3900 persons and we have 3300 prisoners, which amounts for 82% of occupancy rate. So, it’s a much better situation compared to eight years ago. Actually, we regularly invest in prison facilities, so the conditions are good.

We have three different security regimes: closed, semi-open and open. In the open regime there are no prison guards, people are around the facilities all the time and they work mostly on agriculture and other workshops; in the semi-open regime, people also spend a lot of time outside of their rooms, and we have a progress system: inmates go from closed, to semi-open, to open and then to being released to freedom, first probably under the supervision of the probation service, and to being totally free.

JT: March 2017 marked the visit of the delegation of the Council of Europe’s Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) to the Croatian prison system. The report has been released in October 2018, and it recognises the efforts invested to reduce prison overcrowding. Nevertheless, the CPT recommends that Croatia continues efforts to ensure every prisoner has at least 4m² of living space each in multiple-occupancy cells. Moreover, the CPT is particularly critical of the excessive restrictions imposed on remand prisoners and misdemeanour offenders who usually spend up to 23 hours locked up with no access to purposeful activities. It recommends that alternatives to imprisonment for misdemeanour offenders should be introduced. The report also refers to the lack of proper provision of health care in prisons. (Source: CPT/Inf (2018) 44 available here).

How are the shortcomings pointed out by the CPT being addressed? And, are there any fully implemented recommendations already?

JS: I’m really grateful that the CPT considered the progress that has been made in the prison system. Of course, there are always things that could be better, and that is why we welcome this type of visits. In addition, we have a special national mechanism that includes our Ombudsman being around our prisons and penitentiaries all the time. All recommendations are taken very seriously.

As regards the CPT recommendations, we did everything that we could in accordance with our budget and infrastructural possibilities. For example, when we talk about 4 m2 of living space per inmate, all the prison governors know that they should respect it.

In penitentiaries, our inmates spend a lot of time outside of the cells and in fact, the doors are not locked. Plus, they usually have special living rooms, gyms, they go outside, they work, they have special rooms for the treatment. On those aspects, we have really improved.

When it comes to the health of prisoners, we have a good system because we have internal medical staff, and, in accordance with the recommendations of the CPT, we did hire more people, including technicians and doctors. We now have staff in the places the CPT pointed out. In addition, we have very good cooperation with the public health system: all prisoners are guaranteed the right to health, just like any other citizen. Sometimes recruiting health professionals is quite challenging, it is not just a problem in the prison system, it is a general one as many doctors are trying to get jobs in Western European countries.

In the meantime, we have done something new that I really think will help: we have improved our educational centre. We are preparing many new training programmes for our staff, as recommended by the CPT. So, all that could have been done in a short period of time, we did.

As for the recommendation on creating sentencing alternatives for misdemeanour offenses, this is something outside the intervention area of the correctional service. It is a question of legislative change that we will advocate for. A challenging issue is that despite us currently having alternatives, many convicts don’t want them; they choose to go to prison instead of, for example, paying a fine. There are people who don’t think it’s such a big problem to do time in prison.

JT: You have attended and participated in the creation of the probation system in Croatia, which was established in 2009, during Croatia’s accession negotiations for EU membership.

How would you describe the evolution of the probation system and what is expected from now on?

JS: We, in Croatia, are really proud of our probation system. We have received a lot of compliments from different stakeholders worldwide and in fact, it has been recognised as one of the best models on how to develop a Probation Service by the Council of Europe. The United Nations also considers it a good practice – I’ve just returned from Japan from a preparatory meeting for the U.N. Crime Congress 2020 where I have presented the development of our Probation Service, step by step.

We really did it by the book. We didn’t have a Probation Service before, so, the first step was to pass the law, then we recruited staff, trained them, prepared the offices, the instructions from the headquarters and then we started working with the offenders. From the law, in 2009, it took us two years to build the Service, which began working daily with offenders in 2011.

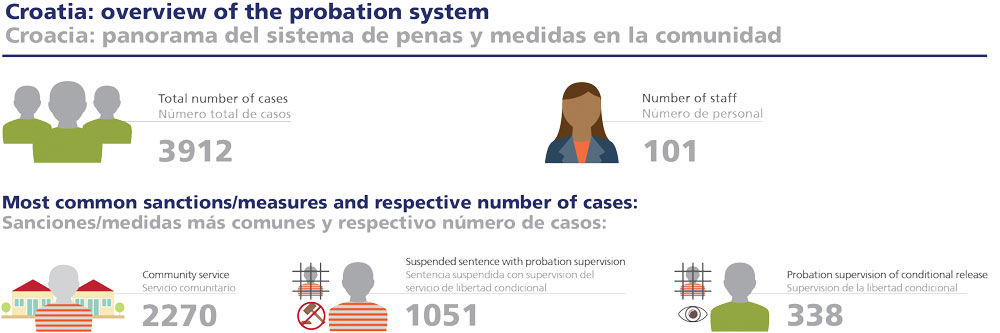

We have been able to lower the number of prisoners by getting many offenders under supervision. And every year the caseload increases, as we are showing the courts, prosecutors and the public opinion that we really do a good job. Most offenders do not re-offend, they find a job, and the Service helps their family circumstances.

We are hiring more probation officers, and this year we opened two new probation offices – we have a total of fourteen offices now. In addition, with the changes to the penal code, the Probation Service was given more and more tasks. In 2018, we also changed the Probation Law to include everything we have seen in practice, in order to achieve more efficiency, more time to work with the offenders, better information for the courts and less bureaucracy.

We pass on the annual report to our Parliament and I am very proud to say that every year this report gets a lot of attention because everybody recognises that Probation is doing a good job.

For the future, of course, we always want to do something more, we are in the process of thinking about implementing permanent electronic monitoring (EM) and last year we had a pilot that showed good results.

The thing is that we like to do everything very thoroughly. That’s why we didn’t start with EM when we first created the Service. Many people wanted to have EM immediately, but we wanted to do other tasks and train staff well, first.

Then we wanted to have a pilot to see how it works, also to see how it works in other countries, to visit their centres and to see the approaches to different categories of offenders and the technological options. Now that we have the knowledge, we can really decide what and how we want it. In addition, we started group sessions with our offenders. We used to only do individual sessions. There are many things in progress and the sky is the limit.

“As regards the CPT (Committee for the Prevention of Torture) recommendations, we did everything that we could in accordance with our budget and infrastructural possibilities.”

JT: To what extent has the cooperation of other European countries helped the maturation of the Croatian prison and probation system?

JS: I’m really grateful to all the countries and colleagues that have been available to show us how they do corrections, especially probation.

Firstly, I would like to mention the Confederation of European Probation, of which I am a board member. When I became the head of the Probation Service, they really helped me to get to know what’s happening around Europe and what the practices are, the good and the bad.

Secondly, there’s the Council of Europe which has multilateral meetings in which you can learn a lot about 47 countries. Also, I became an expert for the Council of Europe which gave me the possibility to work in other countries like Montenegro, Bosnia Herzegovina, and Bulgaria. That experience broadened my thinking because when you are working on a project as an expert it’s always a two-way road: you give, you take, and you learn.

And when we talk about this way of learning, I must mention that we had the great help from European twinning projects and we had some great partners that really gave us excellent lessons on how to have a quality professional Probation Service. We worked with the experts from the UK, Czech Republic, Germany; we had an amazing project with Spain, and we had experts from Romania. Even when we didn’t have a European project, we managed to have some bilateral cooperation like with the colleagues from Norway – which we really look up to, both for prison and probation.

//

Jana Špero was the Head of the Sector for Probation, in Croatia, between 2012 and 2017. She holds a master’s degree in Law and a specialist in Criminal Investigation. As an international consultant of the Council of Europe, she was involved in different activities concerning the development of probation services: workshops, roundtables and projects. She has been engaged as a Council of Europe’s expert in prison/probation projects in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro and Bulgaria, and as a TAIEX expert on probation. From 2016, she is a Board Member of the Confederation of European Probation.