Blog Article

This article explores postcolonial perspectives on prison systems in countries that were once colonies of the West, with a particular focus on the Philippines. It examines the evolution of carceral systems in former colonial nations and the ways in which these systems continue to be shaped by their colonial pasts. In order to challenge and decolonize prevailing ideas about imprisonment, the article highlights a prison in Bohol, Philippines, offering a closer look at the postcolonial transformations within carceral institutions. By drawing comparisons between the Belgian and Philippine prison systems, it underscores the shared systemic issues both countries face, particularly in their treatment of people deprived of liberty. Furthermore, this article aims to highlight how the Philippines, despite its own challenges, offers valuable lessons for rethinking carceral practices, showing that postcolonial countries can offer alternative insights into justice and prison reform.

Postcolonial prisons, like the ones of the Philippines, are here thus referring to the colonial history and the prison system as a postcolonial heritage. To start the dismantling process of this colonial heritage, we make the comparison between the Philippine and Belgian prison system, as the author has most experience with the Belgian system to make proper comparisons between the visit in the Bohol District Jail and a European prison system.

Colonial prisons: Europe’s colonial legacy in the Philippines

European empires did not only export goods and governance; they exported systems of control that reshaped entire societies, including the carceral state. In the Philippines, Spanish and later colonial powers from the US imposed prison structures that mirrored European models of discipline, punishment, and racial hierarchy. The construction of prisons such as the Bilibid in Manila was not an organic development responding to local justice needs, but a deliberate strategy to suppress resistance, reconfigure social order, and entrench colonial authority. The Bilibid Prison refers to a major prison complex built during the Spanish colonial period in the Philippines. It was built in 1865 by the Spanish colonial government in Manila, and designed following European prison models of the time: large, centralised, and focused on containment and discipline. During the colonial period of the US, the prison population had outgrown the old facility and a new prison complex, the New Bilibid Prison, opened in 1940 in Muntinlupa, outside Manila. It remains the main national penitentiary of the Philippines today and houses thousands of people, often in extreme overcrowded conditions.

Colonial prisons criminalised indigenous practices, redefined concepts of “crime” based on European moralities, and systematically marginalised local populations. They introduced incarceration as a primary tool of governance, replacing communal, and restorative approaches. Prior to colonisation, many Filipino communities practised restorative forms of justice. Conflict resolution focused on repairing social relationships rather than isolating individuals. Through community-led mediation, compensation agreements, and public negotiations between families, harm was addressed with the goal of restoring harmony rather than exacting punishment. Incarceration was virtually unknown; only in extreme cases, such as irreparable breaches of trust, might an individual be expelled from their community.

The imposition of European prison systems dismantled these indigenous practices, redefining justice as the state’s exclusive right to punish. It criminalised local customs, introduced racialised legal hierarchies, and normalised the use of cages as instruments of governance. Even after formal decolonisation, the aftershocks remain: overcrowded prisons, punitive criminal codes, and enduring associations between poverty, indigeneity, and criminality.

Decolonising justice in the Philippines—and elsewhere—requires more than acknowledging this history. It demands actively dismantling the carceral logics imported through colonisation and the racialised, class-based power structures that prisons continue to uphold.

Decolonize the prison system

When we speak about postcolonial prisons, the dominant narrative paints a grim and dehumanising picture. In the first season of the Netflix series “Inside the World’s Toughest Prisons” we can find the Philippines. How often have we heard this about countries outside the Western society? Images come readily to mind: thousands of people packed together on bare concrete floors, rampant corruption, torture, and vermin infesting the cells.

While these realities must not be denied, the Western tendency to point outward demands closer scrutiny. For as we condemn the inhumanity of postcolonial prisons, we must also ask: why have systemic problems such as overcrowding, corruption, and degrading conditions persisted for decades within Europe’s own prison systems?

Why is it that overcrowding in Europe is still reality for years in different countries, and judges continue sentencing people to prisons that have already exceeded their official capacities? In the Penal Reform International’s Global Prison Trends 2024, in collaboration with EuroPris, we read the following: “Data from eleven European countries reveal severe prison overcrowding, while an additional five report very high-density conditions, with occupancy rates just above 100%. Cyprus has the highest rate, with 166 prisoners per 100 available places, followed by Romania, France and Belgium, all exceeding 115.”

In Belgian prisons, the notion of a “maximum capacity” exists only in name. In practice, it is routinely exceeded, as courts continue to sentence individuals to incarceration regardless of available space. This systemic neglect has led to chronic overcrowding, despite repeated condemnations by the European Court of Human Rights. People are still deprived of their liberty in facilities where even minimum spatial standards are not respected. Overcrowding is not a logistical issue. It is a political choice.

In response, a group of Belgian prison governors has taken a public stand, urging for a legally enforced ceiling [quota] on the number of persons deprived of liberty. Their message is clear: the prison system cannot keep absorbing people endlessly without collapsing on itself. What they call for is rationality and respect for human dignity within carceral limits.

Why, despite decades of research proving that alternatives to incarceration are more effective, do we still cling to prison as the “civilised” and “humane” response to harm in so-called “developed” societies — a postcolonial term that itself warrants critique? If the prison is a mark of civilisation, what civilisation tolerates caging human beings under inhumane conditions? Alternatives such as restorative justice, community service, probation, therapeutic courts, and electronic monitoring have consistently demonstrated lower recidivism, greater reintegration outcomes, and less harm to individuals and communities. These are not utopian ideas, but evidence-based practices that prioritise accountability and healing over punishment and exclusion.

Why, if research shows that if incarceration is to persist at all, it must be small-scale, community-integrated, and community-integrated, do governments continue to invest in large, industrial prisons — monuments of isolation rather than reintegration? The ongoing work and proven success of organisations like Vzw De Huizen in Belgium and RESCALED across Europe further underline this point for years. Is it still credible, then, to claim that Europe’s traditional, large-scale prisons are models of humaneness?

Still, the large scale prison system endures — not because it works, but because it serves a function. It reassures, controls, punishes, and performs the illusion of justice. In postcolonial societies, the prison continues to symbolise “modernity” and “order” — masking its origins as a colonial technology of domination and its present as a deeply racialised and classed institution. The question is no longer what works — but what kind of justice we choose to uphold, and for whom.

Rethinking the postcolonial narrative

This article does not aim to romanticise or deny the severe problems that afflict many postcolonial prison systems. It seeks to bring nuance. It calls into question the colonial gaze that depicts postcolonial prisons as uniquely barbaric, while absolving Europe’s own systems of similar, systemic violence.

In fact, the global carceral system — including Europe — could learn vital lessons from postcolonial contexts such as the Philippines, where alternative, community-based justice traditions once flourished before colonial imposition dismantled them.

Philippine Prison System

The Philippine prison system is complex, consisting of various types of jails and correctional facilities, each governed by different authorities. It is characterised by a multi-layered structure that spans from local to national levels. Broadly, the system can be divided into three categories: City Jails, Municipal and District Jails, and Provincial and Sub-Provincial Jails.

City, Municipal, and District Jails

These are primarily under the jurisdiction of the Bureau of Jail Management and Penology (BJMP), a national agency tasked with overseeing the management of jails and detention facilities. BJMP-run facilities house people deprived of liberty awaiting trial or serving short sentences. These facilities are notorious for overcrowding, poor living conditions, and limited resources. They are often the most visible form of the penal system, housing the majority of people deprived of liberty across urban areas.

Provincial and Sub-Provincial Jails

Unlike the BJMP facilities, provincial jails and sub-provincial jails are under the authority of the provincial government, which often leads to variations in management and standards across regions. Provincial jails primarily house people deprived of liberty convicted of crimes and serving long-term sentences, while sub-provincial jails are smaller facilities located in rural areas. These jails suffer from the same issues of overcrowding and lack of resources, though in some cases, provincial governments have made efforts to improve conditions, often through limited community engagement or local reforms.

National Prisons

National prisons in the Philippines are managed by the Bureau of Corrections (BuCor), which oversees several large facilities for people deprived of liberty serving long-term sentences. One of the most well-known is the National Bilibid Prison (NBP) in Muntinlupa City. Unlike the city and provincial jails, which focus on pretrial people deprived of liberty or shorter sentences, national prisons house people deprived of liberty convicted of more serious crimes. The NBP, as well as other BuCor-managed facilities, has been heavily criticised for overcrowding, corruption, and inadequate rehabilitation programs.

The fragmented nature of the prison system in the Philippines, with different levels of authority and oversight, contributes to inconsistent standards and management. The BJMP and provincial government-run jails are both overwhelmed by a growing number of people deprived of liberty.

Responsibilities

In the Philippines, unlike in most countries, the Bureau of Jail Management and Penology (BJMP) plays a greater role in the rehabilitation of persons deprived of liberty (PDL) than the Bureau of Corrections (BUCOR). This is mainly due to the extremely slow pace of the justice system.

Pre-trial detention under BJMP is often lengthy: on average about one year for bailable offenses and 3.5 years for non-bailable ones. In some cases, people have spent up to 10 years in jail awaiting trial — and were eventually acquitted. Others who are convicted may have already served most of their sentence in a BJMP facility. For example, someone sentenced to 12 years may have spent 8 years in pre-trial detention, leaving only 4 years in BUCOR custody.

As a result, people spend the majority of their time in the BJMP system, making it the main institution responsible for rehabilitation — even though that role should ideally fall to BUCOR.

Bohol District Jail (BDJ) – a Philippine prison

Responsible Authorities

The Bohol District Jail (BDJ) is a significant example of a local Philippine prison facility that has evolved over time. Previously, the BDJ was owned and managed by the provincial government of Bohol. However, with the implementation of national reforms and the increasing need for more coordinated management, the prison was in 2009 placed under the jurisdiction of the Bureau of Jail Management and Penology (BJMP), the national agency responsible for overseeing local prisons.

Although it has transitioned to national oversight, the BDJ still reflects many of the issues that plagued provincial-run prisons, including overcrowding, lack of resources, and insufficient rehabilitation programs. Despite these challenges, the shift to BJMP-management has led to improvements in the operational structure, though many obstacles remain.

Even though the BDJ is now under BJMP’s direct management, cooperation between BJMP and the provincial government of Bohol remains crucial. The provincial government continues to play a significant role, offering resources, infrastructure support, and local-level interventions to help address some of the challenges faced by the BDJ.

Capacity

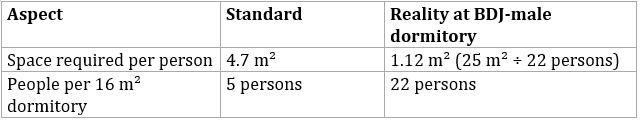

According to Philippine national standards, each person deprived of liberty should be allocated at least 4.7 square meters of living space. This measure is intended to guarantee human dignity and to prevent overcrowding in detention facilities.

At the Bohol District Jail – Male Dormitory, each dormitory measures approximately 25 square meters. There are 29 dormitories available for male people deprived of liberty. Ideally, based on the 4.7 m² standard, a 25 m² dormitory should accommodate no more than 5 individuals. However, in reality, each dormitory houses approximately 22 individuals, vastly exceeding the recommended capacity and leading to critical overcrowding. This severe overcrowding results in 1.12 square meters of space per person — far below what is internationally considered humane. It demonstrates not only the shortcomings of prison infrastructure but also highlights the global nature of systemic failures in incarceration.

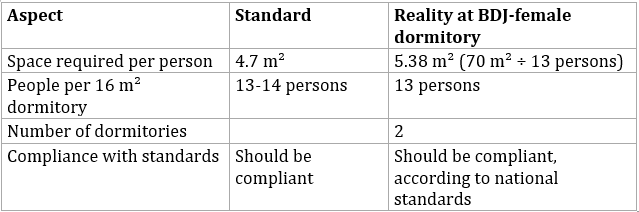

The female dormitory in the BDJ measures 70 m², with two such units available. Based on the national standard of 4.7 m² per person, no more than 13 to 14 individuals should be housed in each dormitory. At present, 13 women are accommodated in one of the dorms, indicating that the official spatial norm is not exceeded.

This observation, however, merits deeper reflection. The mere fact of compliance with national spatial standards does not necessarily imply humane or dignified detention conditions. It is important to consider why the female dormitory, in contrast to other areas, appears to avoid issues of overcrowding. One plausible explanation lies in its relatively small scale. The number of women in detention is often significantly lower than that of men, which allows for more manageable population levels and greater flexibility in the allocation of space. Where male sections of prisons are often subject to chronic overpopulation — driven by structural factors such as longer sentences, higher conviction rates, or broader penal strategies — the female dormitory benefits from a marginal position within the carceral system that, paradoxically, can create conditions less affected by systemic overcrowding. Moreover, small-scale settings tend to facilitate closer oversight, more individualized approaches to detention, and a reduced risk of administrative neglect.

Nevertheless, the fact that a facility meets spatial standards only tells part of the story. Humane incarceration encompasses more than the metric of square meters per person; it includes privacy, access to natural light, the quality of social interaction, and the opportunity for meaningful daily activities.

Prison overcrowding remains a critical issue, also in many European countries, often violating both national and international standards for humane detention. While the European Prison Rules (EPR) stipulate a minimum of 6 square meters per person in single cells and 10 square meters in multiple-occupancy cells, numerous European nations consistently fail to meet these standards. According to the Council of Europe’s Annual Penal Statistics (SPACE I) for 2023, several countries reported severe overcrowding.

According to official statistics, Belgium reports 115 people in prison per 100 available places. Yet this ratio is misleading. ‘Capacity’ is not a neutral metric—it is regularly increased by adding bunk beds or squeezing extra beds into already cramped cells. These adjustments are then simply absorbed into the official capacity count, masking the true extent of overcrowding.

Crucially, this does not tell us how many persons are living with less than the European standard of 6 square meters per person. A more honest metric would calculate overcrowding based on spatial criteria, not on the manipulated notion of ‘beds available.’ This raises critical questions: if we condemn such conditions in the Global South, why do we normalize them in the heart of Europe? And who benefits from statistical framings that obscure structural neglect?

What we can learn from the BDJ

Despite the severe challenges faced by the local prison context, the Bohol District Jail (BDJ), under the management of the BJMP, has undertaken important initiatives that deserve recognition and critical attention.

At BDJ, several efforts have been made to improve the living conditions and opportunities for people deprived of liberty, such as:

Mission and Vision BJMP: Family Oriented

Central to the BJMP’s philosophy are the “Three M’s”: Makatao (Humane), Matino (Upright), and Matatag (Resilient). These core values underscore a commitment to treating Persons Deprived of Liberty (PDL) with dignity, fostering moral integrity, and building resilience for reintegration into society. In practice, the Bohol District Jail has implemented programs that allow for meaningful family interactions, recognizing the pivotal role of familial support in the rehabilitation process. Such initiatives not only humanize the incarceration experience but also contribute to lower recidivism rates by maintaining and strengthening family ties.

Several initiatives exemplify this orientation on the family as a cornerstone of rehabilitation. One clear example is the flexible visiting policy at Bohol District Jail (BDJ), where family members are welcome every day between 9 a.m. and 4 p.m. Visitors can arrive at any point within this window and are free to stay as long as they wish, creating a low-threshold and human-centred model of contact. Also livelihood programs, such as crafting and baking, allow persons deprived of liberty to generate income and support their families, turning incarceration into a moment of contribution rather than disconnection. Products made are sold through various channels, with proceeds benefiting the inmates’ families. Furthermore, the Child-Friendly Visitation Area provides welcoming spaces for children, making visits less traumatic and more relational. Finally, the Kalinga sa Anak ng PDL-program supports the children of incarcerated parents through education, art activities, and emotional care.

These practices reflect a broader ethic of care rooted in community and kinship rather than isolation and punishment. This approach invites a reevaluation of correctional philosophies, suggesting that incorporating family-centered practices can enhance rehabilitation outcomes and promote a more humane correctional environment.

In Belgium, family visitation policies often present significant challenges. Visits are typically limited to three times per week for sentenced persons, with children usually permitted to visit only once per month, subject to prior approval. Visiting schedules and procedures can vary between prisons, but the overarching framework emphasizes strict adherence to set protocols. For instance, arriving even slightly late can result in denied access, reflecting a rigid system that often overlooks the nuanced needs of families and children. While there are initiatives to restore ties with children, these are exceptions rather than the norm.

BDJ takes its family-oriented approach a step further by covering the cost of telephone calls for PDLs. This reflects a broader belief in the importance of sustaining close ties with loved ones during incarceration. In contrast, in Belgium, while efforts have been made to reduce the cost of prison phone calls in recent years, rates still remain a significant barrier for many. Until recently, PDL could pay up to one euro per minute to call mobile numbers — a cost that placed regular contact out of reach for people without financial means. Although some prisons now offer cheaper or subsidised rates through digital systems, access is not universal and inequality persists. As a result, the right to maintain family contact in Belgium is still conditioned by infrastructure and affordability.

So also this example stands in contrast to the practices observed in the Philippines, where the Bureau of Jail Management and Penology (BJMP) implements family-centered programs to maintain and strengthen familial bonds during incarceration.

Person-first Language

One subtle yet significant practice at Bohol District Jail (BDJ) is the consistent use of person-first language. In BDJ — and more broadly within the Bureau of Jail Management and Penology (BJMP) — individuals are formally referred to as Persons Deprived of Liberty (PDL). This terminology is not a cosmetic change: it reflects a fundamental shift in perspective. Instead of reducing individuals to their legal status — as commonly happens in countries like Belgium, where terms like “gevangenen” (prisoners) or “gedetineerden” (detainees) remain the norm — the language at BDJ intentionally places the person before the deprivation.

The term PDL emphasizes that incarceration is merely a condition or circumstance, not the defining essence of a human being. This practice matters deeply. Language shapes perception because the way we speak about individuals can reinforce stigma or break it down. By consciously using person-first language, BDJ helps to reduce the taboo and dehumanization associated with incarceration. It reminds staff, visitors, and the wider community that those inside the facility are, first and foremost, people with dignity, rights, and potential — not simply “criminals”. Small linguistic shifts, when institutionalized, can catalyze larger cultural changes in how societies understand punishment, rehabilitation, and social reintegration.

Working with taboos – community outreach

The Bohol District Jail actively engages in community outreach initiatives that challenge the stigma surrounding incarceration. Jail officers participate in public activities such as educational lectures for criminology interns, promoting transparency and understanding of jail operations. Additionally, BDJ conducts environmental outreach programs, including tree planting and clean-up drives, to contribute positively to the community and the environment.

These activities, however, are exclusively carried out by jail staff, as Philippine law prohibits PDLs from leaving the prison grounds. Despite this, the PDLs participate in various in-prison programs, such as empowerment workshops and educational seminars. These efforts aim to rehabilitate individuals while reinforcing the connection between the prison and society.

Initiatives for Normalisation: Visibility as a Tool — and a Risk

Within the Bohol District Jail (BDJ), the BJMP actively works to dismantle stigma around incarceration — not only through language, but also through visibility. One striking example is their practice of sharing photographs of Persons Deprived of Liberty (PDL) engaged in everyday activities: gardening, learning, performing. These images circulate on official platforms like Facebook and aim to counteract public taboos by showing people being incarcerated as people — not monsters, not numbers, not shadows behind bars.

This approach offers a radically different model than in Belgium or most European contexts, where the prison remains a closed and heavily securitised institution. Images of daily life inside are rare, and where they exist, they are often sensationalist, reinforcing fear rather than empathy. The BJMP’s strategy, by contrast, seeks to normalise incarceration by portraying it as part of the human condition — not as a moral fall.

From a critical standpoint, the potential of such visibility is twofold:

On one hand, it challenges the idea that imprisonment is inherently shameful. By breaking the silence around incarceration, these visual practices may reduce stigma, open doors for reintegration, and encourage a public to reckon with its carceral institutions — rather than hide them.

On the other hand, the permanence of online visibility raises important ethical concerns. Even when BJMP uses black bars to obscure eyes, the rest of the body, environment, and social context may still make individuals recognisable — especially in tight-knit communities. Also this “partial anonymisation” still reproduces a visual grammar of “otherness,” suggesting that these individuals must be marked, even as they are shown. Moreover, once online, these images cannot be retracted. A person who wishes to move beyond their carceral past may forever be traceable through a photo.

While there are clear risks, the fact that Philippine authorities are willing to visualise prison life — and to do so in a way that foregrounds personhood — offers something many European systems have not yet dared: a willingness to let the public see, and be moved, and maybe even take responsibility.

Colourful environment

A notable distinction in Bohol’s approach is the emphasis on green spaces and a colorful environment within the jail compound, in contrast to the stark, grey, and concrete interiors of many Belgian prisons. The presence of plants, trees, and even community-driven environmental initiatives helps to create a more humane and inviting atmosphere. This green environment contrasts sharply with the often sterile, industrial surroundings found in Belgian large scale prisons, which can exacerbate feelings of confinement and isolation. Additionally, the tropical climate of the Philippines plays a significant role in shaping the green environment. The warmth and rainfall encourage the growth of lush vegetation, making it possible for plants and trees to thrive within the prison grounds. This natural, vibrant setting provides a stark contrast to the often cold and impersonal environments in many Belgian prisons, where the lack of greenery can negatively affect emotional well-being and hinder rehabilitation efforts.

Furthermore, the use of color, particularly pink, within the jail’s design is intentional—pink is seen as symbolizing family, health, and rehabilitation. The color is thought to evoke a sense of comfort and emotional connection, further reinforcing the idea that family ties are integral to the recovery and reintegration of incarcerated individuals, says the prison governor.

Participating in Activities

In Philippine jails, Persons Deprived of Liberty (PDLs) do not need to individually register for activities. Instead, dormitory-wide schedules are drawn up by staff to ensure that each group has equal access to programming. This system reduces the sense of isolation and promotes communal participation. In contrast, in Belgian prisons, participation in activities is often mediated by a complex and exclusionary registration process (Termote et al., 2024, in Fatik).

In Belgium, the single-person cell is still considered the standard — often idealised since overcrowding — living condition, yet this model contributes to deep social isolation. PDLs frequently spend the majority of their time alone, and their access to communal or rehabilitative activities is highly unequal. Registration systems rely on written or digital request forms that are not equally accessible to all. Those already engaged in activities are more likely to receive additional opportunities, while individuals who are socially or physically isolated — especially those in long-term cellular confinement — remain uninformed and excluded. This creates a vicious cycle: those who are already visible within the system are repeatedly selected for engagement, while others become structurally sidelined.

The Philippine approach, although far from perfect, offers a practical example of how procedural design — rather than merely infrastructure — can shape more inclusive access to daily activities and programs.

Jail Officers and Staff Structure

At Bohol District Jail (BDJ), a clear distinction is made between two types of staff: licensed jail officers employed by the Bureau of Jail Management and Penology (BJMP), and provincially paid prison guards. BDJ currently has 62 jail officers and 70 prison guards. Notably, all 70 guards are stationed in the male dormitory, while the female dormitory operates without this second category of staff — a reflection of working on a smaller scale, with fewer people to oversee, which allows for more focused and relational staff engagement.

Jail officers receive formal training and are legally mandated to uphold humane treatment. They act as the first point of contact for Persons Deprived of Liberty (PDL), and their role includes rehabilitation and re-entry support, beyond simply maintaining order. In contrast, the provincial guards have no formal training, are not integrated into the BJMP system, and their contracts are reviewed every three months — resulting in high staff turnover and minimal, often superficial contact with PDLs.

Although not directly comparable, Belgium has recently introduced a similar distinction in its newer prisons. Traditionally, all staff operated under a single role structure within the federal system. However, some prisons now differentiate between security officers, responsible for static safety, and detention supervisors, who are meant to serve as primary contact persons and support reintegration (Termote et al, 2024). While a dedicated training programme exists for these supervisors, implementation has been slow and inconsistent. Many staff members are left to learn “on the ground,” without adequate preparation for the interpersonal and pedagogical aspects of their role.

This contrast highlights not only the importance of staff roles and training in shaping prison cultures, but also how smaller-scale systems, like in BDJ female dormitory, can more effectively prioritise relational and rehabilitative approaches over purely custodial ones.

Responsibilities and Roles for PDLs

At Bohol District Jail (BDJ), Persons Deprived of Liberty (PDLs) are entrusted with significant responsibilities that reflect a high level of institutional trust. Some PDLs, ‘the dorm leaders’, are even tasked with holding and managing the keys to their dormitories — allowing them to assist fellow PDLs in moving to and from activities, and to collaborate directly with jail officers. This type of responsibility is unthinkable in most traditional Belgian prisons, where strict hierarchies and securityprotocols prevent such shared control.

Another notable role is that of the ‘jail aid’: 21 men currently serve in this trusted position, supporting fellow PDLs by answering questions and helping them navigate detention life, often in cooperation with jail officers. This peer-led system fosters a more horizontal dynamic within the jail community and promotes shared responsibility and mutual care.

Belgium has experimented with similar ideas — such as buddy systems and the ‘infofatik’ initiative in the prison of Dendermonde (Termote et al, 2024). These are PDLs who act as approachable contact points, providing information on available activities, prison procedures, or offering support to newcomers. However, such initiatives often still face resistance. The core issue lies in the reluctance of prison administrations to place real trust in PDLs — despite the potential benefits for communication, wellbeing, and participation. As a result, peer support remains underdeveloped, fragmented, and vulnerable to institutional pushback.

The contrast with BDJ shows how redistributing responsibility can reinforce agency, build trust, empower PDL, and contribute to a more participatory prison culture.

Structural Limitations and Systemic Challenges

Despite the promising and community-oriented practices at Bohol District Jail, it is important to critically acknowledge that BDJ exists within the broader context of the Philippine penal system — one that faces deep structural challenges. Many of the issues described are not unique to BDJ but reflect inherited problems embedded in the wider criminal justice framework.

The prison system in the Philippines is often deprioritised politically and financially. This lack of investment hampers progress across multiple levels: from persistent staff shortages and inadequate healthcare to limited rehabilitative infrastructure. Overcrowding remains a nationwide issue, with BDJ faring better than most facilities, but still not immune. Its relative success positions it as an exception rather than the norm.

Moreover, prison officers and PDLs alike face social stigma, which reinforces taboos around incarceration and rehabilitation. At the same time, the system continues to be marked by the overcriminalisation of drug-related offences, disproportionately affecting people from marginalised communities.

A further systemic limitation is the strict separation between incarceration and community life. Philippine law does not allow PDLs to leave prison grounds during their sentence, even for rehabilitative or reintegrative purposes. This legal barrier weakens opportunities for building social ties or preparing for release — a critical gap that stands in contrast to the otherwise family- and community-oriented ethos seen inside the jail.

In sum, while BDJ offers valuable insights and alternative practices, its success must be understood within — and constrained by — the broader systemic limitations of the Philippine penal landscape.

Conclusion: Decolonizing the Prison Narrative – Learning from the Global South

This article has sought to unpack the colonial foundations of contemporary prison systems by tracing the historical and structural continuities between colonial carceral regimes and present-day penal practices, with a particular focus on the Philippines. In doing so, it calls into question the presumed moral and practical superiority of Western prison models and opens up space for epistemic reversal: to learn from rather than simply judge the Global South.

First, we demonstrated how colonial powers introduced prison systems not as neutral instruments of justice, but as tools of control and domination, often erasing existing, more restorative and community-based legal traditions. The prison thus arrived not in response to local needs but as an imported mechanism of governance and subjugation.

Second, we argued that contemporary penal systems—both in the Global South and in Europe—continue to be shaped by colonial logics. European critiques of prison conditions in countries like the Philippines often ignore the systemic failures within their own institutions, from chronic overcrowding to structural dehumanization, thereby reinforcing a colonial dichotomy between a “civilized” West and a “deficient” rest.

Third, by reversing this gaze and examining local practices within the Bohol District Jail (BDJ), we illuminated concrete, relational approaches that put human dignity at the center of detention. Despite harsh conditions, BDJ exemplifies efforts to sustain family ties, properly train jail officers, give responsibilities to PDL, create a more humane environment, and so on. These are not marginal gestures but fundamental indicators of a different penal philosophy—one rooted in connection rather than isolation.

Finally, these practices challenge the widespread notion that decent prison conditions are contingent upon economic wealth or high-tech infrastructures. On the contrary, they reveal how cultural frameworks grounded in relationality, mutual care, and community responsibility can offer powerful alternatives—even under conditions of scarcity.

The conclusion, then, is not to romanticize prisons in the Global South or to deny their structural violence—but to recognize the knowledge embedded within practices that have long been marginalized or overlooked. Postcolonial prison systems are not merely residues of colonial rule; they are also sites of resistance, adaptation, and innovation.

If we are to move toward truly transformative justice, we must be willing to learn from these contexts—not as sites of lack, but as laboratories of alternative logics.

This requires us to confront a fundamental question: why do we incarcerate people at all? And if we do continue to deprive individuals of liberty, how can we do so in ways that genuinely serve justice, repair harm, and support reintegration—rather than reproduce exclusion and control?

This includes embracing principles of small-scale, community-embedded detention, as exemplified by the advantages observed in the Philippine female dormitory model. Here, the potential for learning is particularly evident: stronger relationships between persons deprived of liberty (PDLs) and jail officers, increased responsibilities and autonomy for PDLs, more frequent interpersonal contact, and greater access to meaningful activities. These practices directly challenge the logic of mass incarceration by fostering proximity, relational accountability, and reintegration from the outset. The Global South does not need to catch up with the West—particularly not if the destination is a classical, large-scale prison system. Rather, it is we who must catch up with the wisdom that has long existed beyond our gaze, learning both from each other and from the missteps of our past.

Elieze Termote is a Belgian criminologist and scientific staff member at Vrije Universiteit Brussel. Her work focuses on prison reform, Participatory Action Research, and the role of intersectional identities in carceral settings. She coordinated a research project in two Belgian prisons and is affiliated with RESCALED and VZW De Huizen, advocating for small-scale detention.