Article

Frank Porporino

In the last several decades, correctional services around the world have marched steadily towards greater acceptance of evidence-based practice (EBP). The pessimism of ‘nothing works’ has been pretty much abandoned and most correctional jurisdictions would claim that they are at least trying to implement EBP.

Of course, there are continuing challenges in some regions of the world where resources are stretched to meet even very basic needs (PRI, 2023). Yet even in some of these parts of the world, we see serious attempts to embrace EBP (Nafuka & Kake, 2015).

Much of what we now accept as EBP flows from an elaboration of the RNR paradigm, a well-researched framework that has guided the design of rehabilitative efforts for the last 30 years.

In simple terms, the model tells us that we should assess the right kinds of things (i.e., risk factors and criminogenic needs), do the right kinds of things to address these criminogenic factors (i.e., deliver well designed, mostly CBT-type interventions), do those things with the right people (i.e., the higher risk), and do those things in the right way (i.e., engagingly so that individuals will respond).

Undeniably, the RNR paradigm has helped corrections become more structured, organized and focused in attempting to reduce reoffending. At the same time, however, the success we’ve had in implementing

EBPs, either in the prison context or in the community with individuals under supervision, can at best be given a mixed score card.

We know that correctional agencies face significant challenges when trying to provide ‘rehabilitation’ in environments or under circumstances that often act to mitigate the impact of their efforts. In many ways, the influence of regime factors in prisons and some modes or styles of supervision in the community can easily block or undo the influence of our EBPs.

There is considerable evidence, for example, that the experience of imprisonment can actually increase the likelihood of re-offending (Loeffler & Nagin, 2022), as can the experience of community supervision (McNeill, 2018). Correctional agencies may be able to point to various EBPs they have introduced, but the package of tools and practices they have implemented may still have failed to create an overall ‘rehabilitative’ experience.

Efforts have been made to describe the experience of ‘correctional control’ we impose on individuals (e.g., Crewe, 2011 and his metaphors of depth, weight and tightness), but identifying the precise mechanisms at play that allow some individuals to become more pro-social while in prison or during the course of their community sentence remains very difficult to do (Crewe & Ievins, 2020; Maier & Ricciardelli, 2022; Maruna & Lebel, 2012; Mears et al., 2015).

The overriding and still unanswered puzzle is how can we run a prison or manage a community sentence as a process of ‘assisted desistance’ (De Vel-Palumbo et al.; Villeneuve et al., 2021), where how we treat individuals and respond to their issues and concerns leads to a positive lived experience that can help them choose to re-build their lives.

Evolving our understanding of EBPs entails going beyond their formulaic application (e.g., assess – prescribe – intervene). It should compel us to consider all of the possible ‘mechanisms of influence’ that can encourage and support desistence (e.g., not just interventions but social-interpersonal factors, activities, environmental features, family engagement, etc.). Over the last several decades, probation in many parts of the world has moved steadily (even if unwillingly) towards a risk-focused, surveillance approach that has generally made probation less effective (Porporino, 2023). Probation leaders and scholars are now calling for a shift that would see probation move instead towards its original intent of giving disadvantaged and disaffected individuals a chance to reframe their lives (i.e., ‘advise, befriend and assist’).

And so, all this brings us to how we get there. How do we make our methods of ‘correctional control’ (i.e., prison and probation/parole) not just effective at controlling (to serve public safety) but also effective in nudging and supporting individuals towards desistance (which also serves public safety)? What are some of the central issues that need to be dealt with?

Rising to first in importance, in my view, is that corrections needs to take better care of its staff if we want those staff in turn to adopt a more caring and supportive ethos.

Evidence shows convincingly that both community and institutional corrections staff can fall easily into compassion fatigue, feeling over-extended, exhausted, unappreciated, and unnecessarily burdened and confused by the heavily monitored managerialist and accountability cultures we’ve created (Norman & Ricciardelli, 2022).

There are serious consequences for mental and emotional well-being and there is evidence that the longer staff tenure in the job, the worse it gets. Even in Canada, where our staffing ratios are more reasonable, rates of reported mental health concerns have been shown to be worrisomely high for both community corrections staff and those working in custody settings (Ricciardelli et al., 2019). Correctional work has become a career path that may no longer be seen as especially rewarding for individuals with any semblance of human-service orientation. It may attract instead individuals with a punitive bent.

Attending to staff well-being and morale has become a critical issue in the correctional world and we need to start making serious efforts in responding to the emotional toll of working in our field, understanding and rooting out its causes and giving this work the respect it deserves as a demanding, multi-layered, multi-tasking human-service avocation, not just a job to cope with.

Incidentally, I believe this applies whether we are talking about the probation or parole officer in the community, the social worker or psychologist working in our prisons, or the teacher, shop instructor, nurse, case manager or prison officer. In a true EBP world, they should all be committed to the same mission of helping to turn around the disengaged and disaffected.

Part of giving correctional work the respect it deserves entails giving staff a meaningful say in how we manage and change the nature of their work. It shouldn’t be at all surprising that front-line staff will naturally interpret and modify policy and practice in their own ‘real world’ according to their own personal values and assumptions.

We need to learn how to manage the fact that many of our current EBPs can be easily miss-applied, superficially applied or even counter-productively applied. The elements may be there but the substance is often missing. For example:

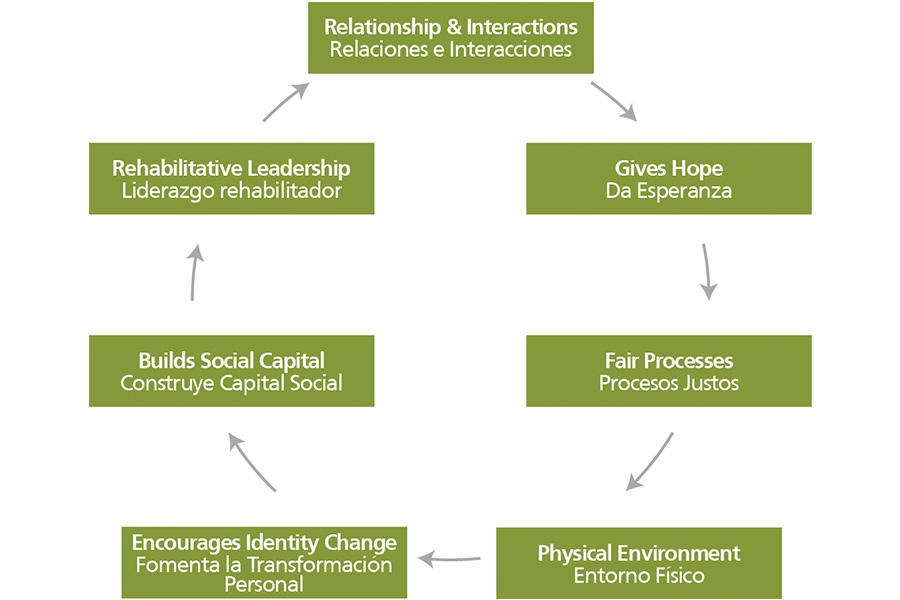

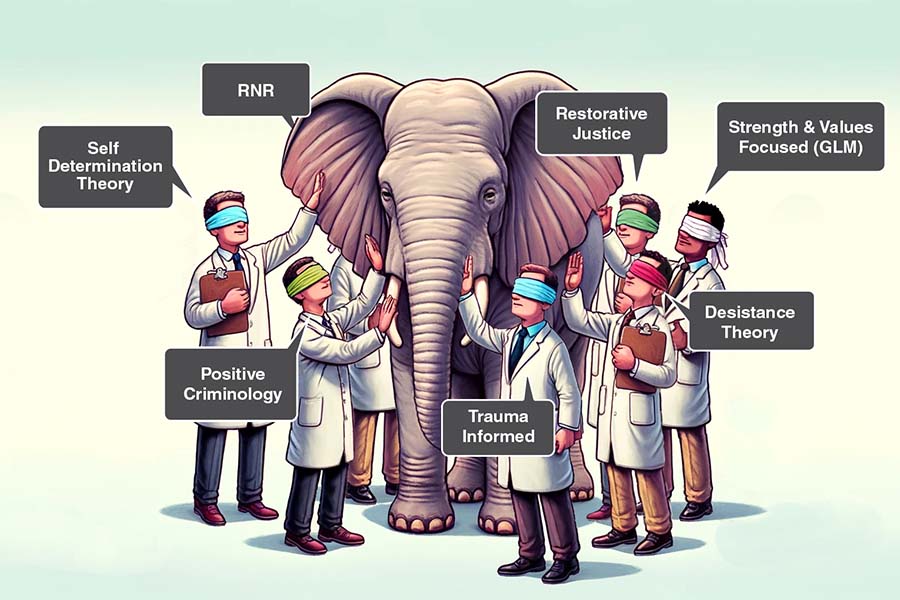

Each practice framework I show as one part of the elephant has its own particular focus and features but there really is no need to see these frameworks as working in competition. Integration means that a one-size-fits all approach is resisted, and in its place, model pluralism is adopted to enable change to happen, and to understand what might initiate it, direct it, sustain it and finally consolidate it.

To quickly illustrate what I mean, RNR certainly offers us a straightforward and compelling explanation of what key dynamic risk factors need to change, but it doesn’t really give us much specificity or clarity about the ‘how’ of change.

Self-Determination Theory is considered foundational in psychology in explaining what underlies motivation to change, where a sense of competence, autonomy and relatedness is both what fuels the change process and then supports persistence.

This is fully consistent with the principles of Positive Criminology that suggest we should focus more on what may be emotionally uplifting for individuals rather than deflating. There is evidence, for example, that the influence of criminogenic risk begins to diminish with the emergence of positive emotions like optimism, hope, self-efficacy and psychological flexibility (Woldgabreal et al., 2016).

Strength and values-oriented paradigms like GLM similarly emphasize agency and a collaborative relationship with the individual that can encourage them to strive towards primary goals that give all of us some sense of life satisfaction and well-being.

Desistance theory reminds us that the path to finding reasons for change is individualized, identity change is not a linear process, some setbacks are inevitable, and trying to force change is counterproductive.

Restorative Justice argues for moral reparation as a key factor in supporting desistance, what the desistance paradigm refers to as satisfying the need for redemption. And finally, there is now growing recognition of what’s been referred to as our ‘residual obligation’ in corrections to address inequalities, marginalization and the impact of trauma, all of which entails a particularly specialized, knowledge-informed practice framework.

Practice frameworks operate as conceptual maps offering distinct but complementary perspectives (Ward & McDonald, 2022). Each has its own set of core values and principles and multiple frameworks may apply for any given individual in addressing the complexities and challenges of their particular way out of crime.

But at the end of the day, how we pursue EBP should mean that all of our processes, procedures, policies, programs, community links, agency values and modes of interaction with individuals should be consistent with ALL that we know about the human change process, and about desistance from offending in particular.

Correctional practice should of course be grounded in evidence, but it should also rely on sense and sensitivity; sense in how we incorporate a broad range of evidence into the design and delivery of our services to offenders and sensitivity in how we go about nudging change gradually but steadily rather than forcing and shaping it within time-limited interventions (Porporino, 2010).

This isn’t easy to do for either correctional agencies or individual staff, but good correctional work isn’t easy to do and if we try to make it easier it won’t work.

References

Carleton, R.N.; Ricciardelli, R. et al. (2020). Provincial Correctional Service Workers: The Prevalence of Mental Disorders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 17 (7), 2203.

Creavin, A., Murphy, N., Regan, E. (2022). Young men’s experience of psychological formulation as a part of a Case Planning Initiative in the Irish Prison Service. Advancing Corrections, Vol. 2, 80-90.

Crewe B (2011) Depth, weight, tightness: revisiting the pains of imprisonment. Punishment & Society, 13(5): 509–529.

Crewe, B., & Ievins, A. (2020). The prison as a reinventive institution. Theoretical Criminology, 24(4), 568–589.

De Vel-Palumbo, M., Halsey, M. & Day, A. (2023). Assisted desistance in correctional centres: From theory to practice. Criminal Justice & Behavior, Vol. 50, No. 1, 1623-1642.

Lewis, S. (2016). Therapeutic Correctional Relationships: Theory, Research and Practice. London: Routledge.

Loeffler, C. E., & Nagin, D. S. (2022). The impact of incarceration on recidivism. Annual Review of Criminology, 5(1),133–152.

Maier, K., & Ricciardelli, R. (2022). “Prison didn’t change me, I have changed”: Narratives of change, self, and prison time. Criminology and Criminal Justice, 22, 774–789.

Mann, R., E. (2019). Rehabilitative culture Part 2: An update on evidence and practice. Prison Service Journal, 244, pp 3-10.

Maruna, S., & Lebel, T. (2012). The desistance paradigm in correctional practice: From programmes to lives. In F. McNeill,P. Raynor, & C. Trotter (Eds.), Offender supervision (pp. 65–87). Routledge.

McNeill F. (2018). Pervasive Punishment: Making Sense of Mass Supervision. Bingley: Emerald Publishing.

McNeill, F., & Schinkel, M. (2016). Prisons and desistance. In Y. Jewkes, J. Bennett, & B. Crewe (Eds.), Handbook on prisons (pp. 607–621). Routledge.

Mears, D. P., Cochran, J. C., & Cullen, F. T. (2015). Incarceration heterogeneity and its implications for assessing the effectiveness of imprisonment on recidivism. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 26(7), 691–712.

Nafuka, N., & Kake, P. (2015). Implementation of the Offender Risk Management Correctional Strategy (ORMCS): From a punitive to a rehabilitative approach. Southern African Journal of Criminology, no.1/2015,101-113.

Norman, M., & Ricciardelli, R. (2022). Operational and organisational stressors in community correctional work: Insights from probation and parole officers in Ontario, Canada. Probation Journal, 69(1), 86-106.

Porporino, F. (2010). Bringing Sense and Sensitivity to Corrections: from Programs to ‘Fix’ Offenders to Services to Support Desistance In Brayford,J., Cowe F., & Deering,J. (Eds.) What Else Works? Creative Work with Offenders. London: Willan Publishing .

Porporino, F. (2022) Can Less Correctional Control Give Us More Public Safety: Working to Make Community Options More Effective. Invited Opening Address, Fifth World Congress on Probation and Parole, Ottawa, Canadian Community Justice Association.

Prison Reform International, (2023). Global Prison Trends 2023.

Raynor, P., Ugwudike, P., & Vanstone, M. (2014). The impact of skills in probation work: A reconviction study. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 14(2), 235-249.

Ricciardelli, R. et al. (2019). Correctional work, wellbeing, and mental health disorders. Advancing Corrections Journal, 8, 53-69.

Ugelvik, T. (2022). The transformative power of trust: Exploring tertiary desistance in reinventive prisons. The British Journal of Criminology, 62(3), 623–638.

Viglione, J. (2019). The risk-need-responsivity model: How do probation officers implement the principles of effective intervention? Criminal Justice and Behavior, 46(5), 655–673.

Villeneuve, M.-P., F-Dufour, I., & Farrall, S. (2021). Assisted desistance in formal settings: A scoping review. The Howard Journal of Crime and Justice, 60(1), 75–100.

Ward, T., & McDonald, M. (2022). Practice Frameworks in the Correctional Domain: How Values Drive Knowledge Generation and Treatment. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 66(9), 1001-1016.

Woldgabreal, Y., Day, A., & Ward, T. (2016). Linking positive psychology to offender supervision outcomes: The mediating role of psychological flexibility, general self-efficacy, optimism, and hope. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 43(6), 697–721.

Frank Porporino has a Ph.D. in clinical psychology and a close to 50-year career in corrections as a front-line practitioner, senior manager, researcher, educator, trainer, and consultant. Frank has promoted evidence-informed practice throughout his career and his contributions have been recognised with awards from a number of associations including the ACA, ICCA, Volunteers of America and International Corrections and Prisons Association (ICPA). Currently he is Editor of the new ICPA practitioner-oriented journal, Advancing Corrections, Chair of the ICPA R&D Network, member of the ICPA Practice Transfer Advisory Comittee and Board Member and Secretary for the ICPA-North America Chapter.