Interview

John May

Co-founder and President of Health through Walls

What motivated you to dedicate your career to providing healthcare to prisoners and to found Health through Walls?

JM: It’s the privilege to make a difference in the lives of so many that brought me into correctional healthcare, and it’s the example and dedication of amazing colleagues that keeps me going.

While at home one evening in the USA in 1999, I saw a TV documentary on how funds from USAID were ineffective at assisting the justice system in Haiti. The reporter went into the National Penitentiary in the capital city, Port-au-Prince and witnessed shocking conditions of overcrowding and the misery of thousands of persons behind bars awaiting trial. I was a physician at the local jail at that time and was moved by what I saw. I decided that I’d like to travel there to see what assistance I might be able to provide.

At first, I was unable to make the right connections. Undeterred, about a year later, I took the two-hour flight alone from my Miami, Florida home and to Port-au-Prince without having any contacts in Haiti. At that time, I was unaware of a global correctional community and the strength that comes from an organisation such as the International Corrections and Prisons Association, but I knew from my experience in the USA that professionals working in corrections share a bond and are driven to make improvements.

I made my way to the prison without knowing the language or landscape, and it took several days of knocking on doors and setting up meetings. I was fortunate to meet Michelle Karshan, a US citizen working in Haiti who established a programme, Chance Alternative, to assist persons deported to Haiti following criminal convictions in the USA. Michelle had some knowledge of the system and helped to navigate the channels. Eventually, the collegiality from prison officials was extended and I made my way into the prison.

I was stunned by what I saw. I thought that surely a year after an international documentary of desperate conditions, someone or some agency would have done something. But, in fact, it was just as bad or worse than what was shown on TV.

From that day onward, I could not leave it alone. The prison officials were supportive since they just wanted a better work environment for themselves and the persons in their care. I started making short trips once each month on the weekends when I wasn’t working. I purchased supplies at home and carried suitcases of soap, toothpaste, medications, and equipment.

Eventually, correctional colleagues learned of the need and efforts and volunteered to assist, helping to collect donations and supplies or offer services. At each visit, long lines formed as we started evaluating and treating the medical needs of the incarcerated persons. That’s how it started.

Over the years, we have worked with dozens of countries and received funding from diverse agencies such as USAID, AIDS Healthcare Foundation, the US Department of State International Narcotics and Law Enforcement, The Global Fund, UNAIDS, TB REACH, Gilead Foundation, Elton John AIDS Foundation, and individual donors, particularly past volunteers or friends and family who are very familiar with our work.

We presently have nearly 170 local staff working in prisons of Haiti, Dominican Republic, Jamaica, Malawi, Mozambique, and Central African Republic.

We are led by Ivan Calder, our incredible CEO, who works and travels tirelessly to respond to the many requests and needs while seeking funding from every corner, and heroes such as our Chief of Party in Haiti and team who continue despite unimaginable deterioration in their country.

Can you share some insights into the unique challenges faced in delivering healthcare within correctional facilities in developing countries?

JM: Most often, the desire to deliver and support appropriate care is strong, but the resources or know-how is lacking. Additionally, for a medical professional, the prison can be very isolating.

Unless the custodial and health staff respect and collaborate together, the morale is low, and outcomes are poor. Even in programmes where Ministries of Health are to deliver care within prisons, those going into the prison can find a lack of direction or support. We find that building a community of professionals, sharing and exchanging ideas and goals, and being a resource can go far to improve systems.

A curious obstacle has been many of the protocols from institutional health agencies intended to guide health development in low-resource countries. They are not designed for the situation in prisons. For example, for many years the World Health Organization (WHO) promoted the best strategy to screen for tuberculosis in low-income countries was asking persons if they have cough, fever, or weight loss.

It did not support the use of technology as this was not considered cost-effective. But if you ask thousands of persons inside an overcrowded prison if they have any of these symptoms, almost everyone would say yes.

And when we tried to advocate for a better system such as digital chest x-ray, we were told that the guidelines don’t support this. Fortunately, with that example, the WHO now endorses chest X-ray screening in prisons as we have demonstrated its efficiency and success.

How does Health through Walls collaborate with correctional administrations to improve healthcare delivery in prisons? To what extent is HtW able to engage with and influence relevant policy decisions to ensure its sustainability?

JM: Frankly, there have been times when we’ve needed to inject ourselves into a system because we found nothing but neglect. Mostly, however, it is the thoughtful invitation of correctional or health leaders for us to review their system and offer advice or support to make improvements. In either case, we necessarily build a relationship so that everyone shares in the good outcomes and improvements in environment, health, and safety.

We seek external grants, community partnerships, and professional associations to build sustainable systems. We train local staff and remain a resource. We build bridges across governmental agencies and systems so that all recognise the stake they have in maintaining an adequate health system within the prisons.

JT: Health through Walls Haiti has been recognised with the Global Correctional Health Award 2022 for using technology and Artificial Intelligence to improve health outcomes for the identification and management of tuberculosis. We also learned about HtW’s ECHO project, using online video meetings to provide training to correctional healthcare staff and incarcerated persons.

Can you tell us more about HtW’s innovative approaches, and how bringing modernisation efforts to low-resource contexts can contribute to your mission?

JM: There are many exciting technologies that can assist us in population health. HtW has deployed and trained several prison systems in the use of digit chest X-rays to screen for active tuberculosis disease. Traditionally, X-ray films would be sent to a radiologist for interpretation. The turnaround took several days and was expensive.

Now, we can use WHO-approved artificial intelligence systems to interpret the X-rays and alert us within minutes if the person likely has tuberculosis disease. The individual can be immediately isolated to reduce the risk of contagion and begin the path to cure with treatment.

Even for low-income countries, technologies like this can prove to be cost-effective while making a big impact on disease control.

The technological hurdles are few, and we can be adaptable to make it successful. Project ECHO is an international distance learning programme which we have introduced to correctional environments with a focus on HIV, hepatitis, and other diseases.

We have hosted monthly 1 hour virtual programmes in English, Spanish, French, and Portuguese for health workers in prisons across many countries. We share challenging clinical cases and seek the guidance of subject matter experts on how best to manage them.

People join the conversations through Zoom connections on their cell phones or computers. The model is “all teach, all learn”. This experience improves collegiality, reduces isolationism, and builds our community of dedicated prison health providers. But we also host a similar ECHO platform for incarcerated persons to share their experiences.

We’ve equipped systems with laptops and internet access. Select groups of incarcerated persons sit before the laptop camera and engage in a monitored session with groups of incarcerated persons person from other countries to discuss similar or different experiences or attitudes on disease in prison, staying healthy in prison, reducing risks, or eliminating stigma. There is great power in education from peers as we learn from each other.

What message would you like to convey about the importance of Health through Walls’ mission to potential partners and supporters?

JM: Our work has grown across the globe and made an impact because we’ve assembled a mission-driven team able to assist often with few resources but a whole lot of passion, grit, and solidarity. Yet, nearly 70 years since the adoption of the now-designated Mandela Rules, the tragedy is many low-resource systems do not meet the minimum health rules.

We find many gaps in health care. Preventable disease flourishes. Treatment is missing. Services are not available. There are so many needs. Our goal is to help systems where, at the very least, they do not cause harm but instead develop into a system that promotes and engenders health and well-being.

It does not take much to make a difference except a belief in the value of each human being.

To learn more about Health through Walls, become involved, or make a donation, visit the website: www.healththroughwalls.org

John May

Co-founder and President of Health through Walls

John P. May, MD, FACP, is the Chief Medical Officer for Centurion LLC, a leading provider of health care services in jails and prisons across the United States. A recognised professional with several Service and Excellence awards, he is also a Clinical Assistant Professor, at the Department of Internal Medicine at NOVA Southeastern University Dr. Kiran C. Patel College of Osteopathic Medicine, and Affiliated Professor at Emory University Rollins School of Public Health. Dr May is Chair of the International Committee of the American Correctional Association, Board Member of the International Corrections and Prisons Association, and is on the Editorial Advisory Board of the Journal of International Prisoner Health.

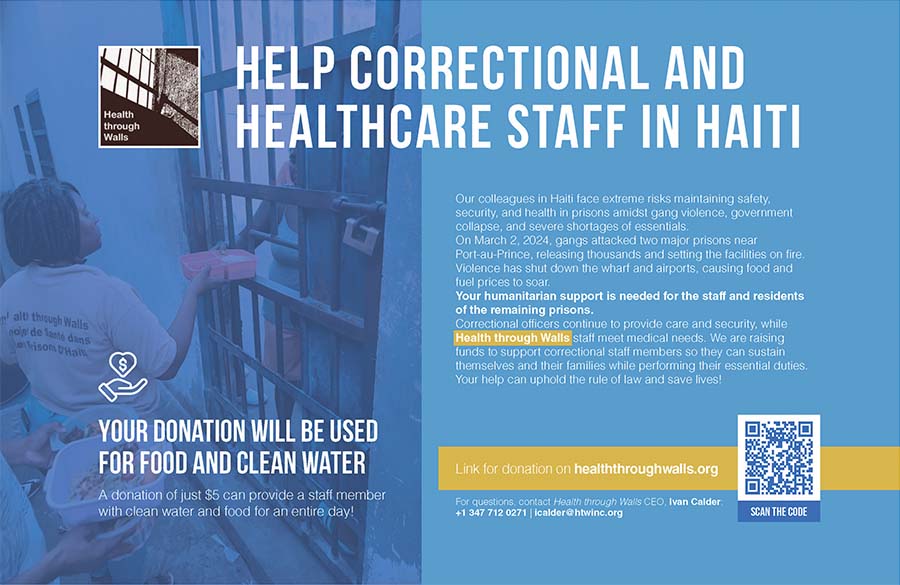

Advertisement