Interview

Heidi Washington

Director of the Michigan Department of Corrections, USA

In recent years, Michigan has drawn attention for its structured approach to rehabilitation within the prison system. Under the leadership of Director Heidi E. Washington, the Department of Corrections has prioritised access to vocational training, post-secondary education, and practical re-entry support.

In this interview, Director Washington outlines the thinking behind programmes like Vocational Village and Offender Success, and reflects on the importance of routine, structure, and access to tools that prepare individuals for life after incarceration. She also speaks about the challenges of aligning different stakeholder priorities, the role of technology in modernising both security and daily life inside facilities, and how knowledge-sharing through international networks is helping to shape more effective correctional practice across jurisdictions.

How would you describe the department’s priorities and challenges today?

HW: Our priorities continue to centre around the population we supervise. We are focused on education, employment, and rehabilitative programmes, including cognitive and therapeutic support. We are seeking to promote a culture centred on success. It is through investment in these areas that we can help individuals succeed, both while incarcerated and as they transition back into the community.

A challenge is the fact that no matter how much progress we make, there are always multiple, often competing, stakeholders who have their own set of priorities. And those priorities don’t always align with ours. For example, there are individuals and organisations in the advocacy space who may focus on certain outcomes that don’t necessarily line up with workforce priorities.

That is always a challenge, but it’s also an opportunity to bring different stakeholders together and provide education on how we can work toward shared goals because, ultimately, we all want the same thing: safer facilities that provide real opportunities for people to lead productive lives. When that happens, it also improves the workday for the staff who operate within those institutions.

Another priority of ours has been continued investments in technology and the modernisation of our facilities. Whether you live or work inside a prison, the environment has a direct impact on how you feel about your day, your job, and even yourself. And so, we are continuing to make significant investments in our infrastructure, modernisation, and technology.

With technology, one of the biggest challenges we face is the pace at which it evolves. It moves fast, often far faster than the bureaucratic processes of acquiring it.

We may get excited about a new technology available on the market, but by the time we navigate the full acquisition process, the technology has already advanced.

That can leave us with something that’s no longer the latest advancement, despite the significant time, energy, and money we have invested. So, one of the challenges is making government processes more efficient, which would be very helpful.

JT: Over the last decade, MDOC has established structures like the Vocational Village and expanded re-entry support through Offender Success, signalling a commitment to rehabilitation as part of public safety.

Can you expand on what these approaches consist of?

HW: The Vocational Village is the first of its kind: a skilled trades training centre located inside a prison. We opened the first one in 2016, then created a second at another facility, followed by a third. Since then, we have continued to expand on those efforts.

Essentially, we are teaching in-demand trades while working closely with hundreds of employers across the state to meet both their workforce needs and the needs of our students. We focus exclusively on programmes that are credentialed or certified. In other words, individuals don’t just walk away with a certificate from the Department of Corrections, they leave with a legitimate state or national license or certification, which is very important. They are fully prepared to leave prison and go straight into the workforce on day one, and often as some of the most skilled workers available. Employers are telling us that directly.

A big part of the model’s success is that we use state-of-the-art machinery and equipment. This was not the case in the past, but with growing investment, our students are now learning on industry-standard tools and technology.

To get into the programme, individuals must apply. First, they are required to demonstrate and articulate that they are ready to make this kind of commitment because, once accepted, they are moved into the Vocational Village, where they will live in a housing unit with others in the programme, separated from the general population.

Everyone in that unit is focused on their goals, and they attend the Village every day, all day. It’s designed to replicate a real-world work experience and what employers expect from workers: go to work every day, show up on time, and putting in a full day’s effort. That kind of structure is not something many people in prison have been accustomed to. Participants are learning together, living together, and receiving comprehensive wrap-around support.

Complementing the Vocational Village, we offer a robust vital documents programme. In fact, about 99% of individuals leaving prison each month do so with their vital documents in hand. That includes a state ID or driver’s license, a birth certificate, and an application for a Social Security card. These documents are critical to a successful reentry because without identification, you can’t get a job, secure housing, or access many basic services.

Additionally, we work very closely with employers, many of whom are inside our facilities on a daily basis. They are learning about the training programmes we offer, the quality of the programmes, and developing real relationships with prospective employees. They are also conducting interviews on site, making job offers, and in many cases, individuals are leaving prison and starting work the very next day.

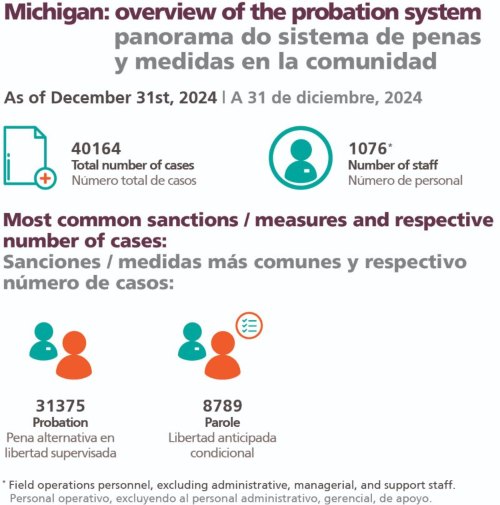

About the Offender Success division, it was created back in 2015, when I became the director. In Michigan, our department is responsible for probationers, prisoners, and parolees. That includes people on probation in the community who haven’t yet entered the prison system (and we hope they never do), people who are incarcerated in our facilities, and people who are leaving prison and will be supervised on parole in the community. All of these individuals fall under our umbrella.

We wanted to create a division within the department that focused on success for everyone, and provided opportunities no matter where someone was in the system. The goal was to target, create, and promote success at every level. Often, because of the large number of people on the incarcerated side, that’s where all the resources tended to go. But our goal is to shift some of those resources to the front end of the system, in the community, as a priority. If we can help people turn things around before they enter prison, that’s what we want to do.

We use all evidence-based programmes in areas such as violence prevention, substance use disorder treatment, and cognitive programming. We are trying to address the underlying criminogenic risks and thinking that often leads to criminal behaviour and promoting long-term success.

In addition to these services, we have contracts throughout the state with community service providers who help deliver services to people on probation and parole in the community. We are also very heavily engaged and invested in delivering post-secondary education, in other words, college inside prison. We currently partner with 12 colleges and universities in Michigan that deliver higher education directly to our incarcerated population.

What impact have you seen so far, and where is there the most room to strengthen or expand on these initiatives?

HW: Our recidivism rate is currently about 22.7%. Relatively speaking, that’s a pretty low rate here in the United States, and we attribute that success to many of the efforts we have been discussing.

When we look at the people who have participated in our education programmes, especially those in the Vocational Village, we see that individuals who go through the Village are employed at a higher rate than those who don’t have the opportunity. From the programme’s launch through July 2023, we found that the recidivism rate among village participants was 12.6%. So, we know that we can reduce the recidivism rate nearly in half through the vocational village.

And even the smallest change is still a big change. Because ultimately, if we are helping change just one person, the hope and the goal is that we can have an impact on others in that community, on the people in that person’s life, and on the generational cycle of incarceration.

We hope that by creating success for these men and women, their children won’t follow the same path to prison. We are actually seeing evidence of that in our educational programmes. We are seeing incarcerated parents who are enrolled in college courses inside prison, and their children, out in the community, are enrolling in college too. They are doing college together, at the same time. We are seeing that more and more now and, honestly, that’s very inspiring.

Our recidivism rate is currently about 22.7%. Relatively speaking, that's a pretty low rate here in the United States.

JT: As Board Member and President of the North American Chapter of the International Corrections and Prisons Association, you are directly involved in knowledge-sharing of best practices across systems worldwide.

Are the results from Michigan’s efforts helping shape those conversations as examples of good practice?

HW: One of the reasons why I became involved in ICPA was to have the opportunity to represent the U.S. and to tell the story of the positive things happening in U.S. corrections. And there are many, many positive things. Vocational Village and post-secondary education are two strong examples. Through my involvement in ICPA, I have had the opportunity to share these as examples of best practices at events and conferences around the world, with colleagues from other jurisdictions. That’s been one of the real benefits of that involvement.

We did a webinar with ICPA focused on workforce issues. I presented alongside a couple of other speakers, and I was able to share about the Vocational Village. It generated a lot of interest. That’s just one of the ways we are sharing information and hopefully encouraging others to adopt similar programmes – by showing them what we have done, so they don’t have to reinvent the wheel. That’s the value of being involved in organisations like ICPA, you get to learn from your colleagues, people who have already done the heavy lifting. We already have a plan. If someone wants to create a Vocational Village, we can tell them what it takes, what the setup looks like, what the costs might be. We can help them get started and share ideas.

Because of the exposure I have gained through ICPA and through the Correctional Leaders Association (CLA), which is the national organisation here in the U.S., we have been able to do just that. We have hosted international visitors and over half of the U.S. states have come to Michigan to see what’s happening with the Vocational Village. This network of professionals is working to share good ideas, support each other, and replicate success without having to start from scratch every time.

You mentioned a focus on modernisation earlier. How do you see the role of innovation shaping the future of corrections in the state?

HW: When it comes to technology, there are countless solutions that help us perform our work more efficiently and effectively. This has become more important than ever, for several reasons. First, because we are all struggling with staffing shortages, no matter where you are.

We are working to educate ourselves and explore new ways of doing things, whether it’s AI or other forms of technology that can create efficiencies and free up staff time. That way, staff can focus on their core responsibilities, rather than getting bogged down writing reports or pulling data from outdated systems, things that likely already have a tech solution, or at least an emerging one.

Continuing to modernise our facilities and bring in advanced security technology is also critical. It helps keep people safe and helps us do our jobs better. We also need to invest in technology for the people who live in our facilities. Because they are going to re-enter a world that’s completely different, even if they have only been incarcerated for five years. For some, it’s been 10, 15, 20, even 30 years. We have to prepare people to thrive in a digital, tech-driven society. That means making sure they have access to technology while they are inside, so they are not stepping out into a completely unfamiliar world.

Here in Michigan, we are also exploring how we can provide virtual experiences to help incarcerated individuals understand what that world now looks like, how they will be expected to interact with it

Think about all the things we take for granted: going to the grocery store and using a self-checkout, going to the bank or the ATM machine, checking in at the doctor’s office on a kiosk. All of these things can be intimidating and daunting for someone who’s been away from modern life for a long time.

We are also currently in the middle of a very large project to Wi-Fi enable all our facilities. It’s a multi-year effort, and once we have a secure Wi-Fi network established across all our facilities, including classrooms and housing units, we will be much better positioned to deploy technology to our population. This will expand opportunities and allow more people to be productive each day. They will be able to access technology not just in the school building, but right from their housing units. With this access, individuals can still spend their time productively by accessing educational materials electronically and getting a head start, right from their cell or room.

Heidi Washington

Director of the Michigan Department of Corrections, USA

Heidi E. Washington is the Director of the Michigan Department of Corrections, where she oversees the state’s prisons, probation and parole supervision, the Parole Board, and other administrative functions. Her previous roles include warden at several facilities and leadership positions in administration and legislative affairs. She holds a BA in political science from Michigan State University and a law degree from Thomas M. Cooley Law School. Director Washington also participates in national correctional and justice committees, including the Correctional Leaders Association and the Integrated Justice Information Systems Institute.

Advertisement