// Interview: Peter Severin

Commissioner of the New South Wales Corrective Services (NSWCS), Australia

JT: How are the correctional services organised in Australia?

PS: In Australia, all of the states and territories are independent in terms of their judicial and correctional system. Each state has its own legislation and criminal code, and there is also federal law. So, for offenders who are convicted for offences against the federal law, wherever you commit the offence and are convicted, that’s where you serve your sentence.

While states and territories have separate systems, we work very closely together. Administrators meet twice a year to share practices and look to leverage opportunities for improvements from one another.

We don’t have a federal agency that has anything to do with prisons, and the federal government is very clear that that is not an area they want to get involved in.

JT: What can you tell us about the New South Wales Corrective Services (NSWCS) human resources and their training?

PS: We have a national curriculum which is slightly different in each state but our training programs are aligned, so an officer in one state can also become an officer in another state through a bridging program.

For a prison officer, training is between nine and twelve weeks to start with, and then they have a year within which to complete a Certificate 3 in Correctional Practice. Our specialist staff such as psychologists, social workers, and educators have a university degree.

What we have very clearly identified as a gap, which we are closing, is while we have very solid fundamental training, we don’t have a very good managerial training. This is about developing people who understand human resources, finances, and operations in a much-applied way.

So, we have designed very specific training programs for middle managers and prison governors which will give them much better tools to become more effective. Moreover, there is a national executive leadership program that is very applied and specific.

We always get about three or four commissioners or Directors-General to lecture, as well as academics and other justice leaders. Although it is still evolving, this program is very strongly based on the relevant areas that we need to focus on.

JT: It was under your leadership that the Correctional Department of South Australia managed to reduce the recidivism rate by 10% for several consecutive years.

What did you do to achieve that? And have you managed to replicate “the formula” in NSW?

PS: It was an effort made by all parts of the criminal justice system and also within a political environment that was open to drive change and reduce reoffending.

There was a very strong relationship between the prosecution, defense counsels, the courts, police, and corrections, and we were quite successful in identifying alternatives to imprisonment. We identified, for example, that 45% of our remand population was in prison for less than 14 days! So, we organised initiatives outside the custodial environment, such as helping an accused find a place to live.

It was quite unique, and some of the elements continue to be very relevant today. In New South Wales, there were similar efforts made between 2009 and 2011 and recidivism decreased, however, unfortunately, this decrease did not continue. Right across Australia, policing has become more and more efficient – because there has been a stronger focus on law enforcement and stronger penalties – so we end up having more persons in custody.

Crime is a societal problem. It is only if you actually make all parts of the criminal justice system – if not all of the human services – work very closely together, that you achieve change and a sustainable reduction in incarceration rates; prisons on their own cannot do it. It is a collective effort and it requires political will.

Policing has become more and more efficient so we end up having more persons in custody.

JT: In Australia, the New South Wales state already has the largest network of prisons, and, right now, it is expanding its infrastructures.

Can you please tell us more details about such expansion?

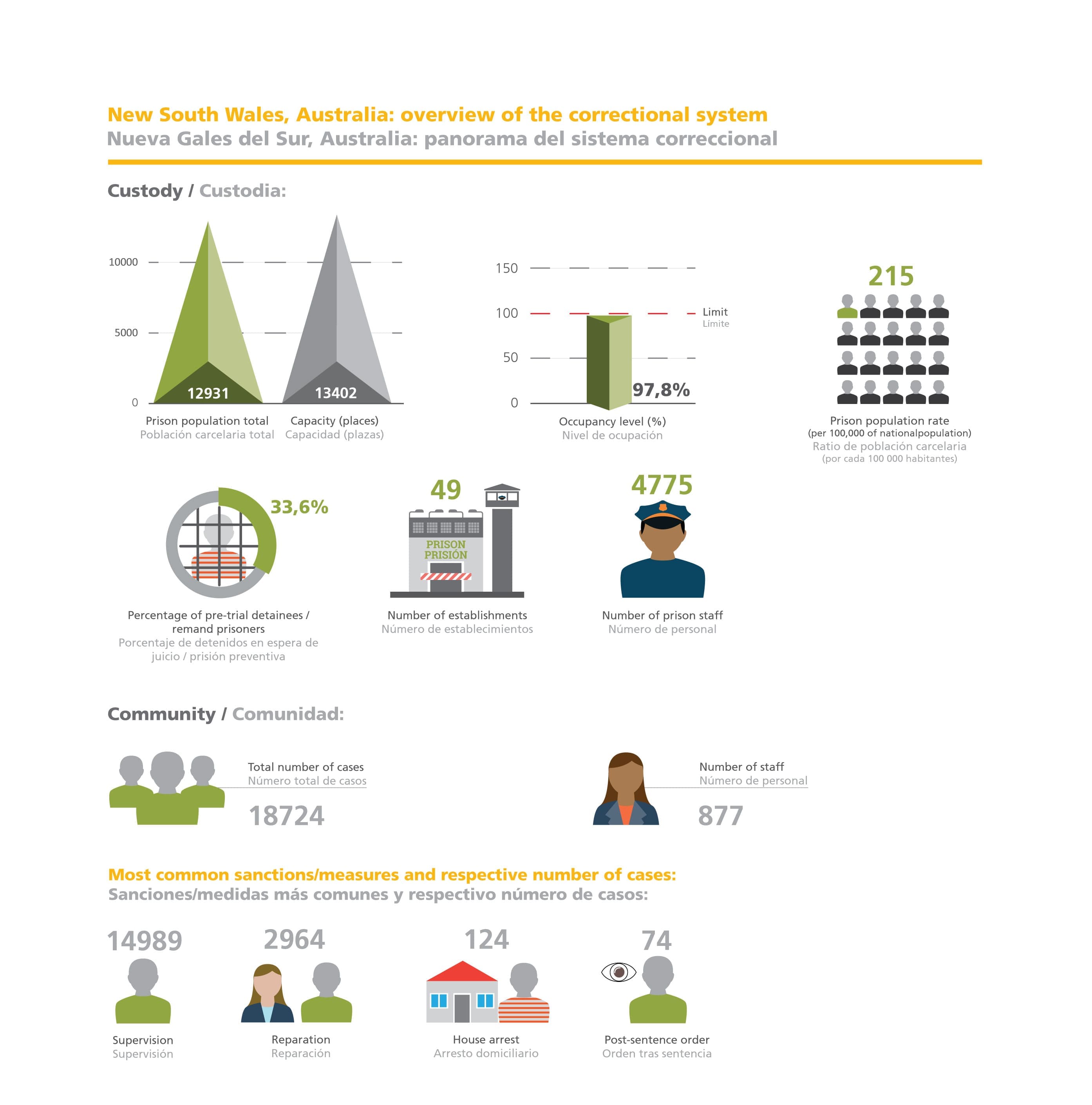

PS: Based on the change in trend and the increase in prisoner numbers, we have experienced growth going from 9 500 prisoners to about 13 200 within two to three years.

Of course, no system can absorb such an enormous increase in numbers over such a short period of time. So, the government committed AU$3.8 billion (US$ 2.9 billion, €2.4 billion), 2.4 of which is for the capital infrastructure, and 1.4 is to actually operate it. That is a significant investment and means 5 000 additional beds.

We are also looking at streamlining our system better through a strategy that will lead us to be more efficient in the way we use and configure our infrastructure.

However, the only way to make a sustainable change and get the balance between the use of community-based corrections and prisons right, is by also having a very strong focus on legislative reform and identify what else works in a way that doesn’t result in an eroding of the community confidence in our mission, but that actually complements a well-configured criminal justice environment.

We are building, we are expanding existing prisons, we have constructed some rapid-build prisons which were procured within a very short period of time and constructed within 12 months.

Furthermore, we are building a new 1700-bed facility as a public-private partnership (PPP/PFI) – the private consortium is designing, building, operating, maintaining and financing it, so it will be privately managed – and, hopefully, at some stage, we will be able to decommission the old and obsolete infrastructure that we still have.

JT: How are these new prisons in terms of design and technologies?

PS: We use technology quite extensively – obviously for security, by making sure that we can optimise safety – but more and more also through the use of in-cell technology, which is interactive and manages routine administrative tasks. That will come online very shortly, and we need to make sure it does do what it promises and be responsible.

As far as design is concerned, Australia has looked far and wide for good designs, and wherever we have a new prison built it seems to enhance and improve what was there before, particularly on greenfield sites.

Our prisons have large footprints and a lot of open and outdoor space.

We try to create zones where prisoners can actually live in a quiet open way, a sort of open campus-style prison, even for maximum-security prisoners who are suitable.

We have come up with a quite exciting modular configuration which can literally be stacked in an aesthetically pleasing way, but it’s a very fast procurement and from a technology perspective it’s also able to be retrofitted or immediately fitted with all those modern technologies that the industry offers us these days.

The government committed AU$3.8 billion, a significant investment that means 5000 additional beds.

JT: There is a large over-representation of indigenous citizens in Australia’s prisons. In NSW, although the indigenous community represents less than 3% of the total population, it amounts to 25% of the state’s prisoners. (Source: The Sydney Morning Herald, 27/11/2014).

How have you been addressing this challenge?

PS: It’s a societal problem that administrators, politicians, and anybody involved in the criminal justice system is acutely aware of. Alternatives to prison will allow a much more proactive dealing with this reality, however corrective services, on its own, can do very little.

We do have pathways for indigenous people in our system: specific and culturally appropriate interventions, and a very strong focus on indigenous women.

There is no short answer as to how to constructively and sustainably address the overrepresentation of indigenous people in our system. We have come up with some good initiatives however the challenge is that a lot of those are not sustainable.

JT: How has the experience of being a member of the ICPA Board been to you, and to what extent has it contributed to your work as a commissioner?

PS: The ICPA is the world-leading organisation on matters relating to corrections, the administration of correctional systems, and those issues and solutions that actually make a difference and need to be pursued by all jurisdictions.

Bringing together the public, private and non-government sectors, as well as researchers and academics, is a fantastic form to learn the latest practices and then implement them where they make sense. I have done that quite extensively.

I was elected to the Board in 2010 and have been the Vice-President since 2014, so I am very grateful for having the opportunity to meet many colleagues, from all parts of the world, to have a very intensive dialogue, to learn all the things that actually have been identified as making a difference, and to exchange and share my own learnings with others.

Most recently, I have started to capitalise on working in this global context: every six to eight weeks I connect my executive team with one of the commissioners, Directors-General, or academics from around the world; we have a Skype session and talk for one hour about their experiences. It is a great opportunity for them to learn and get the full benefit of engaging in this exchange.

JT: What challenges do you consider to be most pressing for the correctional system you lead?

PS: Clearly, a challenging issue is reoffending. The NSW Government has set very ambitious targets for us to make a difference. Besides the infrastructure program, we have also been provided with AU$237 million, over four years, to introduce legislative and programmatic change in the way we are dealing with offenders.

That has been done in different ways: probation orders have been streamlined through amendments to the sentencing legislation essentially into two orders: one is an Intensive Corrections Order which hopefully will see many people who might get short sentences be given an alternative in the community that might involve electronic monitoring and compulsory participation in programs, and the other is the Community Supervision Order that deals with the low-risk offenders and community corrections.

By having just two community supervision orders, we hold quite a bit of hope that community corrections become more attractive to the courts.

We also are looking at our intervention programs for violent and sexual offenders, cognitive behavioural-based programs for drug and alcohol misuse, domestic violence, and a particular focus on indigenous offenders.

So, without some very tangible effort in relation to structuring the prison reality in a meaningful way, I don’t think that corrective services will continue to contribute well. Fortunately, our government has given us the means to implement changes.

The second challenge is the need to do more and better with less. There’s clearly a requirement to consistently look at our effectiveness and efficiency. We have been running a very strong program of commissioning our services in the most advantageous and efficient way.

We also have a government that is interested in market testing, meaning that we want public operations to be able to stand up to private sector competition. We actually have run a market test of an existing facility with three of the big private sector companies engaged in tender together with an in-house bid.

To everybody’s surprise, the in-house bid won and we were certainly very proud of that. So, that is demonstrating that the public sector was really trying to rise to the challenge, that it can deliver services as effectively – if not more effectively – and efficiently than the private sector can.

JT: How do you picture the future of the New South Wales Corrective Services?

PS: I would like to think that we will see a much greater use of community-based supervision. I want a continued professionalisation of our workforce at all levels within the organisation, and I also would like to think that our infrastructure program is not just providing more beds, but actually streamlining our system to make it more efficient.

Hopefully, we will continue to be a strong partner in the criminal justice system, together with the other agencies such as the courts, police, defense counsel, the prosecution, and others, to have a system where the community can feel safe, can have confidence that the justice system delivers well, and that reduces the harm it can cause to those that actually are in the unfortunate situation of having to serve a term of imprisonment.

//

Peter Severin started his career in Germany, back in 1980. Before joining the Corrective Services of New South Wales (CSNSW), he was the Chief Executive of the South Australian Department for Correctional Services for nearly ten years. Previously he had been the Deputy Director General of the Queensland Department of Corrective Services, where he worked for more than fifteen years. He joined the CSNSW, as its Commissioner, in September 2012. He has been a Board member of the International Corrections and Prisons Association (ICPA) since 2010. He has a degree in Social Work and a master’s in Public Administration.