Article

Margarida Damas

Polarisation and populism are growing worldwide, greatly benefiting from misinformation and disinformation campaigns alongside geopolitical tensions. Despite the worldwide nature of the phenomenon, Europe has been greatly impacted. In fact, in 2019, around 50% of EU citizens experienced hate biases (Fundamental Rights Agency, 2021), which is reinforced by the most recent picture displayed by EUROPOL’s threat analysis. Its latest report showcases how European countries are experiencing increased incidents and calls to violence across the entire ideological spectrum, targeting different communities, including online and stemming from varied groups (EUROPOL, 2025).

With the normalisation of intolerance, which in today’s setting is seen in the political, social, digital and private realms, hate and extremism f ind breeding grounds to mushroom. By affecting individuals, groups and communities, with a lasting effect on victims and the core values of the European Union, the current landscape reinforces the needs and challenges of victims, communities and justice systems. Indeed, these challenges start from the get-go, with the Fundamental Rights Agency displaying how over 50% of hate and extremism-related incidents fail to be reported (2021). Reports and assessments have shown how the fear of secondary victimisation, the lack of trust in the justice system’s abilities, and the lack of grounded and up-to-date information are shaping these figures, especially as European countries are struggling to create integrated legal responses to the phenomena in their full complexity.

Moreover, considering the local impact of hate and extremism, solutions are also required at the community level, building resilience to them, which means knowing how it manifests, but also how to prevent it. Nevertheless, challenges also appear for justice systems. Firstly, criminal justice professionals and procedures struggle to support victims, mostly due to the difficulties in ensuring their sustained role and participation in the process. Secondly, when working with those responsible for the harm, justice systems must successfully ensure their accountability and development away from extremism, crime, hate and intolerance.

Assessed challenges: Major needs and potential solutions for criminal justice systems

This concern has also been voiced directly by the European Commission, bringing victims’ rights and needs to the forefront, calling for comprehensive, empowering and ideally victim-centred approaches, as seen through the Victims Directive, put forward in 2012, and later, through the EU Victims Strategy. To achieve this, as directly stated in the EU Victims Strategy back in 2020, victims’ needs and voices must be amplified and activated, striving to promote procedures, both within the criminal justice system and in connection with civil society, that are responsive and respectful, yet also sustainable for communities and conducive to resilience building. This is especially relevant in cases of hate and extremism, since the specificities of the phenomena entail pervasive consequences for those suffering from it and their communities, who may be left in especially vulnerable and harmful situations.

Therefore, and following the European Commission’s lead, innovative solutions must be devised from within and beyond the criminal justice sector to ensure a victim-centred approach to hate and extremism, ensuring their participation, empowerment and healing, contributing to reintegration and rehabilitation, by extension (European Commission, 2020).

“Criminal justice systems require innovative and comprehensive solutions, activating victims’ rights and voices, while also contributing to rehabilitation.”

Nevertheless, as stated above, criminal justice systems also face challenges when it comes to working with those responsible for hate and extremism-motivated incidents. Most European countries’ overarching goal of successful rehabilitation and reintegration, following either a disengagement or deradicalisation¹ approach, has been challenged, as recent events and attacks have demonstrated (Lowry, Shaikh & Lewis, 2024). Perhaps the most well-known cases of this mismatch are those of newly released persons who, upon fulfilling their sentences, went on to commit violent and hateful attacks, motivated by intolerant worldviews and extremist milieus. However, and importantly, disengagement and reintegration, even though individual-level processes, and similarly to crime desistance, are a two-way street, with both criminal justice systems and communities playing a role in supporting change, fostering acceptance and building the space for accountability and stabilisation (Raets, 2022). Consequently, a key argument emerges, that of using well-known and tested ‘generic’ criminal prevention mechanisms that are participatory to promote disengagement from hate and extremism.

Restorative-led practices: The road ahead

When aiming to promote innovative and effective solutions for victim support and following the EU Victims Strategy, victims of crime must be empowered via effective coordination efforts, improved support and protection services and safe spaces for reporting. As a result, the EU has reinforced the need to invest in restorative justice solutions for all criminal incidents. The same applies to cases of greater vulnerability, including those of hate and extremism, especially as restorative solutions provide victims ‘with a safe environment to make their voice heard and support their healing process (European Commission, 2020, p.6)’. Importantly, restorative-led practices, following a philosophy of listening, participation and accountability, have also shown potential to work on the rehabilitation away from hate and extremism. According to Tim Chapman, analysing efforts adopted in Northern Ireland shows how restorative principles can promote critical reflection and potential disengagement from extremist milieus, allowing empathy and personal responsibility to be worked on, especially relevant since these are often absent for those associated with hate and extremism (Chapman, 2018).

By promoting transformative processes for those who caused the harm, their victims and communities, restorative-led principles can make a sustainable difference in preventive and interventive efforts. Consequently, when it comes to its use to support cases of extremism, restorative justice must be understood as a set of values and principles that showcase how harm can be dealt with through participatory approaches. By doing so, it upholds and respects victims’ rights and needs, easing their empowerment and healing. Furthermore, it can also be leveraged as a key step towards desistance and disengagement, working on individual and social needs, whilst involving important social networks, thus helping to rebuild a sense of connectedness and pro-social perceived identity, both for victims and perpetrators (Biffi, 2021).

Previous experiences, mostly in Spain and Northern Ireland, have showcased the positive use of restorative-led principles in cases of extremism.

These positive results highlight how restorative justice has been mistakenly perceived as soft and ineffective. Consequently, some of the greater benefits include the establishment of a dialogic process, the promotion of greater empathy, the involvement of community stakeholders, and development of shared and sustainable solutions. For such, a strengths-based approach is fostered, moving away from risk, culpability and weaknesses, to focus on responsibility, participation and reparation.

This means that restorative justice does not need to replace the well known criminal justice system solutions, as these also fulfil important principles, but rather complement them. Through dialogical and participatory possibilities, which are especially relevant for hate and extremism-driven cases, both victims’ voices are taken seriously, and rehabilitation processes are promoted, valuing agency and community resilience.

A commitment to restore justice through a victim-centred lens

Recognising the need to ensure responses to hate and extremism are effective, and inspired by victim-centred approaches, the VicTory project is developing a horizontal approach to promote the effective implementation of legislation and practices that protect victims’ rights and foster adequate support, directly mobilising restorative practices.

The initiative is led by the Euro-Arab Foundation for Higher Studies in Spain, in partnership with IPS_Innovative Prison Systems, the Faculty of Law of the University of Porto, Associazione Carcere e Territorio, Ararteko the Ombusdman of the Basque Country, Map Finland, the Hungarian Helsinki Committee and ILGA Portugal, and funded by the European Commission, through its Justice programme.

As part of its efforts, the VicTory project will promote cooperative synergies between key governmental and non-governmental professionals, invest in continuous capacity-building, and develop evidence-based and needs-oriented restorative-led solutions to hate and extremism. By departing from the needs of victims and practitioners, as well as identified, evaluated and validated good practices, the restorative-centred programme to be developed will be tailor-made to promote empowerment, healing and reintegration.

¹ These concepts carry different implications. Disengagement refers to withdrawing from violence, irrespective of remaining beliefs and ideology. Deradicalisation refers to a cognitive shift away from beliefs, attitudes and ideologies.

References

Biffi, E. (2021). The potential of restorative justice in cases of violent extremism and terrorism. Radicalisation Awareness Network.

Chapman, T. (2018). “Nobody has ever asked me these questions”: Engaging restoratively with politically motivated prisoners in Northern Ireland. In O. Lynch & Argomaniz, J. (Eds.), Victims and perpetrators of terrorism: Exploring identities, roles and narratives (pp. 181-196). Routledge.

European Commission (2020). EU Strategy on victims’ rights (2025). European Commission.

EUROPOL (2025). TE-SAT European Union Terrorism and Trend report 2025. EUROPOL.

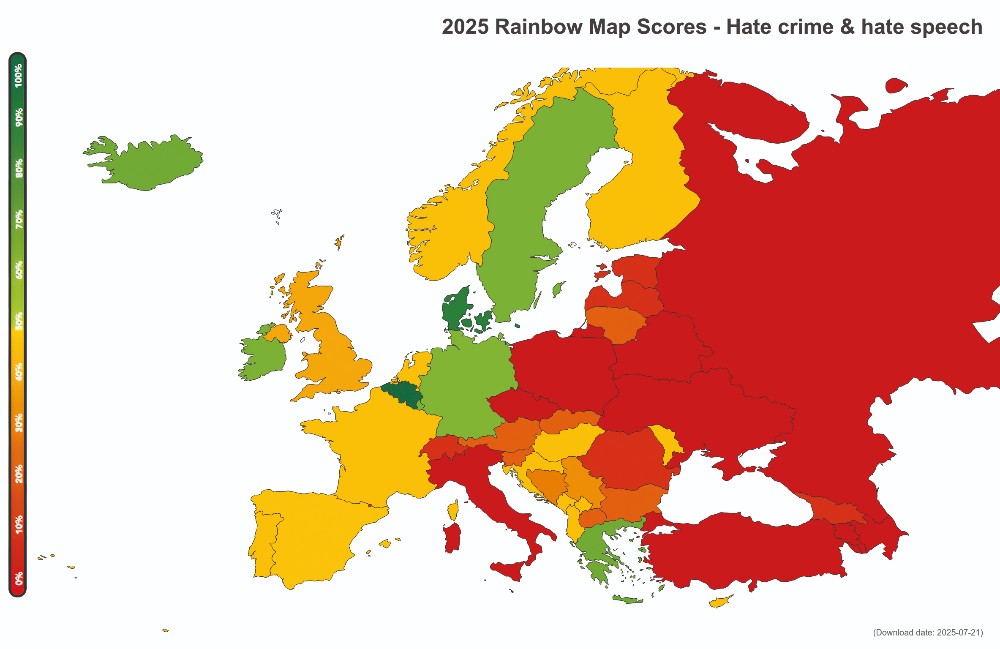

ILGA Europe (2025). RAINBOWMAP: Hate crime & hate speech 2025.

Fundamental Rights Agency (2021). Encouraging hate crime reporting: The role of law enforcement and other authorities. FRA.

Lowry, K., Shaikh, M. & Lewis, R. (2024). Research and Practitioner Perspectives on the Rehabilitation and Reintegration of Violent Extremists. National Institute of Justice Journal, 285.

Raets, S. (2022). Desistance, disengagement, and deradicalisation: a cross-field comparison. International journal of offender therapy and comparative criminology.

Margarida Damas is the Head of Unit for Community Inclusion and Social Development, as part of the Radicalisation, Violent Extremism and Organised Crime Portfolio at IPS_Innovative Prison Systems.

Margarida is a criminologist, holding a Master degree in Sociology, from the University Institute of Lisbon (ISCTE-IUL), with a specialisation in Human Rights. As part of her commitment to improve integration and build more resilient communities, Margarida recently completed a post-graduate degree in Risk Intervention and Inclusion Promotion, granted by Lusófona University. Margarida is a certified trainer, and has extensive experience in training community and educational practitioners on comprehensive techniques to prevent radicalisation and promote social inclusion.