Interview

Toon Molleman

Deputy Director, Division of Prisons and Foreigner Detention, at the Dutch Custodial Institutions Agency, The Netherlands

In this interview, Deputy Director of Prisons, Toon Molleman, shares insights into the in the Netherlands’ evolving approach to detention and rehabilitation. We discuss how the Dutch prison system addresses current challenges, such as staff shortages and capacity constraints, while maintaining a strong focus on humane conditions. He also explains the role of prison-based work programmes and support for finding employment outside prison for those nearing release, as well as the importance of early assessments to build effective, person-centred rehabilitation pathways.

What are the most pressing challenges facing the Dutch prison system today, and what priorities are shaping your approach to managing them?

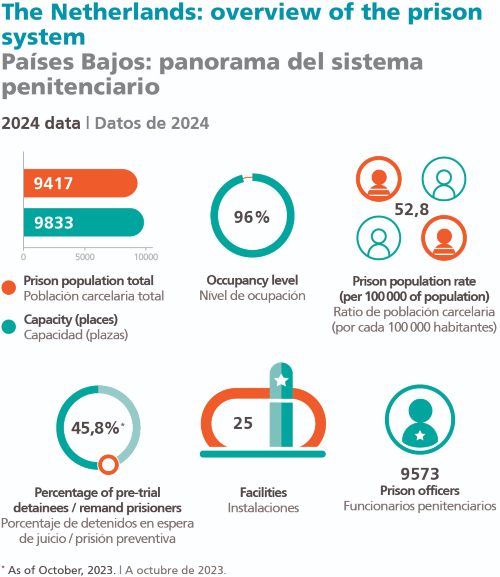

TM: We currently face several pressing challenges. Among the most pressing are issues related to cell capacity and staff shortages. I believe these challenges are common across many countries in the Western world. Here in the Netherlands, the challenges are in creating sufficient detention capacity, attracting and retaining enough staff, responding effectively to high-risk individuals in custody, improving reintegration into society, and addressing an increasingly complex prison population.

Until 2018, several facilities in the Netherlands were closed due to declining crime rates. The Netherlands became somewhat well-known for this over several years. However, we are now looking to increase capacity by creating more cells, expanding the use of multi-person cells where appropriate, introducing early release options for low risk individuals, and identifying suitable halfway houses to support a structured and monitored transition from prison to society.

The issue of staff shortages is closely linked to the pressure on detention capacity. When staffing levels fall below our minimum standards for a wing, we are required to empty and close that wing until we can restore adequate staffing.

Humane detention is central to our approach. Another principle we strongly uphold, and of which I am quite proud, is that we never exceed the design capacity.

Despite the current pressure on capacity and staffing, we continue to prioritise safe, decent conditions for both staff and people in custody.

For example, we only allow double-bunking if the wing provides adequate amenities and services, including access to outdoor space, workshops, kitchens, or other necessary facilities.

We have assessed every cell in the Netherlands to determine whether the available amenities and services are sufficient to support double- bunking. This includes evaluating ventilation and air quality, ensuring that the infrastructure of the building can support the physical and environmental needs of two occupants per cell. This approach reflects our commitment to maintaining the quality of detention, and the prison service is not willing to accept a decline in standards. Nobody sleeps on a mattress on the floor.

We are also working hard to enable the early release of low-risk individuals in the coming months. Our approach is always guided by the principle of doing justice and offering second chances. This motto, which comes from the policy level, is something we put into practice every day by combining humane detention with meaningful preparation for life after custody.

How do you see the significance of In-Made and Ex-Made as models for work-based rehabilitation, particularly in comparison to more traditional prison labour schemes in other countries?

TM: The Netherlands has developed a work-based approach to reintegration and rehabilitation, which is achieved through two initiatives: the In-Made programme, which provides meaningful labour opportunities within prison, and the newer Ex-Made initiative, which focuses on external work placements for people nearing release.

These programmes now encompass dozens of prison-based production units and certified vocational training pathways. As part of my role overseeing the Dutch prison system, I also monitor the performance of individual prisons in implementing their In-Made and Ex-Made activities.

In the In-Made programme, I evaluate each prison based on workshop capacity, participation levels, and outcomes. While the workshops do contribute modestly to offsetting operational costs, that is not their primary purpose. The main goal is to provide incarcerated individuals with meaningful work experience that aligns with their individual reintegration plans.

They have the opportunity to develop skills in areas such as metalwork, woodworking, or cleaning services, and obtain relevant diplomas and certifications. These certifications are not optional; they are an important performance indicator in our evaluation.

This focus on skill-building and certification forms a central part of the management relationship between prison headquarters and individual facilities. It reflects our commitment to ensuring that reintegration efforts are both practical and tailored to each prisoner’s future prospects.

JT: The Netherlands’ person-centred approach includes drafting a Detention & Reintegration Plan (D&R-plan) for every person entering the system, based on Income, Screening and Selection (ISS) screening data and updated throughout the sentence.

Can you walk us through how these tools work together in practice, and how they help shape more individualised, effective rehabilitation pathways?

TM: Every person in detention receives an individual plan during the f irst phase of their stay, based on the first intake assessment, known as the ISS. This screening focuses on what we refer to as the five basic needs for reintegration: income, housing, debt resolution, care, and having valid identification. Criminological research has shown that addressing these needs is critical in reducing the likelihood of reoffending.

This takes place in the first few days and lays the groundwork for the reintegration plan, which is updated throughout detention. This way, each person follows a tailored path back into society.

For over a decade, every prison in the Netherlands has had a Reintegration Centre. Here, people can get help with housing registration, dealing with debt, or finding work. These services link directly to the five core needs.

After six weeks in detention, everyone receives an Individual Detention and Reintegration Plan, which outlines their personal goals and how to meet them.

These goals are supported through work assignments, educational opportunities, workshops, sports, and other individualised components of the prison’s daily programme.

When people actively engage with their reintegration plan, and show motivation and progress, they may become eligible to transfer to lower security facilities where they may work outside during the day and access services and amenities in the community. This resembles the concept of halfway houses in other countries. The goal is for them to be able to continue with the same job or support network after their release.

How is the data generated through these tools used to define and track successful rehabilitation?

TM: We use several digital systems that give us insight into the quality and completeness of the information we gather about each person in detention. Some of these systems are quite old, as the Netherlands was an early adopter of automation and digitalisation in the correctional sector. While this gave us a head start at the time, it now poses a challenge as many of our systems are harder to integrate with other solutions, to update or replace. Some other countries that began digitalisation more recently could start fresh with modern systems.

Still, we have strong monitoring and data sources to track progress in reintegration and rehabilitation.

The reintegration information we collect is shared with our partner organisations in the broader reintegration chain, including the person’s municipality and the probation service. This coordinated data exchange allows partners to offer help sooner and more effectively, improving the chance of a successful return to society and lowering the risk of reoffending.

A few years ago, a new law made this kind of data sharing possible for reintegration purposes. Before this, we needed explicit consent from each person in detention, and many said no – sometimes on principle, sometimes due to mistrust. Now, with this legal basis, we can share relevant information between authorised organisations when it helps someone’s rehabilitation. This has made it much easier to coordinate support.

Even when someone is hesitant, we can still act in their best interest, because some people need extra help, whether they realise it or not. And that, to me, is the core of our work: guiding and helping people towards a better path, even if they are not ready to take that first step on their own.

Toon Molleman

Deputy Director, Division of Prisons and Foreigner Detention, at the Dutch Custodial Institutions Agency, The Netherlands

Toon Molleman, PhD, is the Deputy Director of Prisons and Foreigner detention at the Dutch Custodial Institutions Agency (DJI). He previously worked as a prison director of the penitentiary institution of Arnhem and Leeuwarden. Dr. Molleman received his PhD in 2014 at Utrecht University (Methodology & statistics) by creating a benchmark for prisons. During his PhD research, Dr. Molleman worked at the Research and Documentation Centre (WODC) of the Ministry of Justice and Safety.

Advertisement