Interview

Leandro Lima

Secretary of State for Prison and Socio-Educational Administration, Santa Catarina, Brazil

The Brazilian prison system generally faces several challenges, particularly overcrowding and the high incarceration rate. The poor conditions of the prison infrastructure, the shortage of prison staff, including prison police officers, and the proliferation of criminal factions are frequently published in the media. In this interview, Secretary Lima explains how they tackle prison overcrowding and improve living standards in prisons across the State. Prison industries are an example of the measures taken, and they also have the “Revolving Fund” initiative. Our interviewee also talks about the expansion of alternative measures and sanctions, staff training and development, and the challenges and opportunities of the pandemic.

To what extent does overcrowding hinder the State Department for Prison and Socio-Educational Administration to carry out its mission? And what actions are needed or are being taken to deal with the lack of vacancies in prisons?

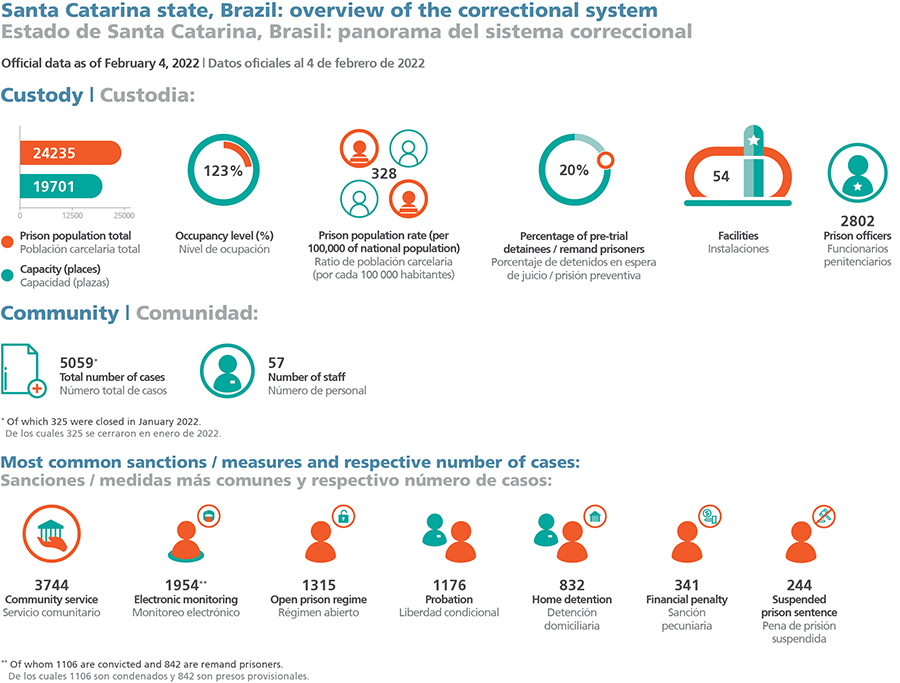

LL: The challenge of building vacancies is pressing, and it should concern most prison systems in the country, as we have a powerful reality of incarceration. Santa Catarina is a state that has a high incarceration rate and keeps people behind bars for long periods. This means that we are conservative in applying the law, both in the matter of imprisonment and in the execution of the sentence.

Clearly, the opening of new vacancies is important for any prison manager, considering the situation of our judicial system. As long as it stays that way, we’re going to need to keep generating vacancies.

I have been a prison officer for over three decades, and I have been working in management for ten years. Lately, we have invested in the regularisation of vacancies, meaning we have transformed existing vacancies into decent spaces for serving a sentence.

In addition, during this period, we built new prison units. We always think of spaces for work and education, corresponding to the number of vacancies in the cells. Now, employment and education occur in different areas from the inmate’s living space, which means a substantial change, as we do not have prisoners working inside the cells.

Moreover, there is no longer handicraft work or any other slave-like work within the prison units. All the work results from agreements signed with almost 260 companies, and the inmate is paid the compulsory minimum wage.

Inmates work for eight hours a day, and they have a break for their meal, a uniform and PPE (Personal Protective Equipment). Another concern is to bring companies from the area where the prison unit is located. This way, when the inmate is released from prison, he is more likely to enter the labour market again.

Despite the construction of new units, the improvement of some others and the closure of old prisons, it is true that we still have some units that need to be demolished to make room for the new ones.

In the next two years, we hope to create at least 2,500 new vacancies. Nonetheless, it will take a few more years to adjust all the necessary vacancies to meet the system's requirements.

What investments have been made in the prison labour and industries?

LL: We have several industries, and the range of products manufactured in prisons ranges from metal to haute couture clothing. It is worth mentioning the textile industry and the furniture industry, too. In addition to the companies, we have twenty municipalities across the State that hire inmates in a semi-open regime. These inmates work cleaning and maintaining streets and in landscaping.

As Santa Catarina is an important textile industry hub in the country, we created the SAP Têxtil program. The initiative involved an investment of more than R$30 million (around €4.7 million / US$5.4 million) in the construction of eighteen industrial warehouses, in the acquisition of hundreds of machines and, also, in the contracting of the National Service for Industrial Learning (SENAI). This organisation provides training to 2,100 inmates who can already work in dressmaking, industrial screen printing, machine maintenance and logistics.

One of our projects is to make school uniforms for the public network of Santa Catarina and produce all textile inputs for the State Department of Health.

I am convinced that the economic activation of prisoners through paid and qualified work increases the chances of social reintegration since they will be able to support their families.

Another fact that draws attention and is favourable is that every prisoner who works has also tried to study in the other shift. When prisoners are working and learning, the tension levels of a prison unit drop, so work and education activities are a security strategy. This is evidenced by that rebellions in Santa Catarina are increasingly rare; the last one was in October 2011.

The economic activation of prisoners through paid and qualified work increases the chances of social reintegration. Every prisoner who works has also tried to study in the other shift. When prisoners are working and learning, the tension levels of a prison unit drop, so work and education activities are a security strategy.

Santa Catarina was a pioneer in implementing the Revolving Fund of the prison system. What does this public policy instrument consist of, and what is its impact in reality?

LL: Prisons are organised into seven regional units. Each has a Revolving Fund with two decision-makers: the regional superintendent and the person responsible for the region’s labour activity.

The Revolving Fund is fed by 25% of each inmate’s wages from the company that hires them as compensation, as provided in the Penal Execution Law. Another source of funds is the profit from the workshops’ operations that the Fund undertakes.

For instance, the cement factory in the Chapecó Prison Complex is a Revolving Fund project. Both the State and the municipalities in the region buy the concrete blocks they need for their works from the prison unit. The profit generated by these sales reverts to the Fund.

So, the Revolving Fund is an experience of regional management supplied with decentralised resources, as it differs from the central account of the State. Furthermore, this tool relieves the State. The regional units are up-to-date with maintenance and care, and are raising their own funds.

Moreover, regional prisons tend to compete with each other. The regional superintendents themselves have sought out trade and industry associations in their region. Currently, we have industrial activity in prisons in all regions of the State. In the Serra e Meio Oeste region, we have the first prison in Brazil with 100% adherence to work from prisoners. This scenario is very positive and supports the selfsustainability index of prisons.

Moreover, the Fund contributes to the rehabilitation of prisoners through work and to a safer atmosphere in the units.

Undoubtedly, this system allows better use of the State’s budget because many prison system expenses are made at a regional level via the corresponding Revolving Funds. Resources from the Revolving Funds have enabled several improvements in prison units, such as changes in the visiting rooms where inmates receive their families, among other works.

Our Revolving Funds system allows better use of the State's budget because many prison system expenses are made at a regional level.

JT: Recently, news published on the Government of Santa Catarina website showed the integration of hundreds of new prison police officers. It also reported that the Governor signed the Prison Police Law.

What needs, progress, and achievements have been attained concerning prison officers (prison police), and how vital is correctional staff training and development?

LL: The new law regulates a series of procedures for which the prison officer was already responsible, in fact. Even more significant than increasing the level of authority, this legal change expanded the prison police officer’s responsibility.

At the same time, we managed to improve their compensation and bonuses. Altogether, I think these achievements will reduce corruption significantly, the entry of illicit items in prisons and even prison breaks.

On the other hand, staff training and development is a pillar that sustains the prison system. Our Academy is the great transformer of human potential, and it is our most significant investment. Education strengthens the role of our agents and the team’s commitment to the activity, thus benefiting the entire system.

We are increasingly bringing the academic world closer to the professional one with this initiative. We recently launched SAPScience, an internal program that offers 650 postgraduate, masters and PhD studies vacancies.

The endeavour is fully funded by the State and exclusively for the State Department of Prison and Socio-educational Administration employees.

There was such an interest that we will have a second edition of the project, with even more vacancies.

We prioritise the investment in our staff to be the great changers in the day-to-day work in the prison units. The system is increasingly open and transparent, so we have fewer cases of corruption and violence.

What has been the evolution of non-custodial sentences and measures, including electronic monitoring? And what is your vision for the future regarding alternative sentences?

LL: Avoiding incarceration is intelligent and educational . In the last five years, we have invested in an increasingly specific way in the Centres for Alternative Penalties and Measures (CPMA, by its acronym in Portuguese). We are currently dealing with more than 5,000 cases in these Centres.

The CPMAs are institutionalised, and they are the result of an agreement between the Executive power, the Judiciary and the Public Prosecutor’s Office.

There are eleven Centres throughout the State, and the goal is to progress. The results are excellent; we have a really low recidivism rate, and, especially in petty crimes, alternative sentences achieve an effectiveness above 90%.

Regarding electronic monitoring, the current number exceeds 2,100 monitored individuals. These are measures that result in low recidivism, but there are still prejudices. People think that the whole system has failed when someone breaks an ankle bracelet, and that’s not true.

We have a secure monitoring system that works 24/7. When there is an issue, it is fixed immediately. The pandemic has promoted greater acceptance of the use of electronic monitoring bracelets. Before, we worked daily and in a Herculean way to convince the judges. Nowadays, that doesn’t happen that often.

Avoiding incarceration is intelligent and educational.

The results are excellent; we have a really low recidivism rate, and, especially in petty crimes, alternative sentences achieve an effectiveness above 90%.

What were the main challenges and opportunities that the public health crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic presented to the Santa Catarina prison system?

LL: In the beginning, the pandemic caused us a lot of fear, a feeling that we hadn’t experienced in a long time. The first reaction was to lock ourselves up in the Secretariat. We even brought mattresses so that, in case we got contaminated, we could isolate ourselves in the workplace.

All scientific guidance pointed out that populations in custody were an extreme risk factor. And we already have numerous cases of TB and HIV/AIDS, so the scenario was scary! But we work every day face-toface both in administration and in operations, as it is impossible to work remotely and take care of 24,000 prisoners.

At our first meeting at the Court of Justice in March 2020, I remember that we built up the idea of a sanitary wall. We installed a Situation Room at the SAP, which did all the mapping of the prison and socioeducational systems.

This information was the basis for elaborating all ordinances and sanitary protocols, always validated with the State Department of Health team. Some doctors guided us daily, giving lectures to everyone involved in the system, from prison officers to judges and public prosecutors.

The Situation Room survey also pointed to the need for products, infrastructure, PPE, and health professionals to assist the prison and socio-educational systems. We hired 120 health professionals in an emergency. We started screening and isolating the prison units, restricting the access of visits – all visits became virtual.

Prison work activities were cancelled for a while, and education became distance learning. In addition to all these changes, we have strengthened hygiene and cleaning measures as much as possible.

Fortunately, the sanitary wall concept was successful; we had a meagre fatality rate, one of the lowest in Brazil; we regret 17 losses (8 prisoners and 9 workers). The structure we set up prevented us from overloading the public hospital network as we could assist inmates with milder symptoms within our prison units. Only the severe cases were sent to hospitals.

I believe that joint strategies involving the Health Department, the State Government, the Judiciary power and the Public Prosecutor’s Office were the key to our success. Although we had to isolate units as a whole – as we had cases of 600 infected inmates simultaneously in one prison complex – the regular multilateral meetings were crucial for an understanding of the moment.

In response to the pandemic, we also created mechanisms that are still in operation, such as a COVID centre that works 24 hours a day. This centre receives case notifications and information from prison officers.

These data allow us to carry out monitoring that, considering trends and statistics, assist in making management and operational decisions fast and assertively.

Every day we publish a newsletter about COVID on the Department website, which shows all the numbers of the prison and socio-educational system: active and suspected cases, number of vaccinated people, and health care, among others.

Vaccination has already exceeded 60,000 doses, involving prisoners and civil servants; the booster dose is also being applied. The vaccine, associated with social isolation, has been effective.

Suppose we can talk about any legacy of this pandemic, which does not refer us to some pain. In that case, it is the fact that we are using more and more technological resources. Today, in addition to virtual visits, we also have virtual hearings and a virtual parlour with lawyers.

JT: The process of public-private partnerships for prison infrastructure involving the Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES) and the Inter- American Development Bank (IDB) is under public consultation.

Why does the State of Santa Catarina opt for a public-private

partnership? How do you see the development of this process?

LL: The IDB’s approach to public-private partnerships (PPP) is fascinating, and it has changed my point of view. Our experience of prisons’ co-management in the last decade needs to be reviewed. There were issues related to cost and control, among others, that moved us away from the shared management modality.

However, this PPP model is an alternative one, as the State’s supervisory power is not sub-established or outsourced in any way. Moreover, it is much more expensive to have a prison officer perform intermediate activities in a prison unit, such as housing and health care tasks.

Thus, we bring together the best of the private sector and the Prison Police, so I’m optimistic about this concept.

I can imagine now prison police officers carrying out 100% of their activity and the private entity developing other actions. Each one with its well-defined role and responsibilities so that none of the parties is affected.

We want the first PPP experience with this format to be successful because, in this case, it will be our parameter to improve for the future.

Leandro Lima

Secretary of State for Prison and Socio-Educational Administration, Santa Catarina, Brazil

Leandro Lima began his career as a prison officer in 1988. A pedagogue, with a degree from the University of Vale do Itajaí (UNIVALI), he had scientific publications in the Journal of the International Observatory of Education in Prisons, of the UNESCO Institute for Education, and in the 1st International Forum of Socio-educational Actions in Prisons, having been awarded the Medal of Academic Merit in 2005. Before his current role in the Justice and Citizenship System of Santa Catarina, Mr Lima served as Director of several penitentiary centres. He was also Director of the Department of Prison Administration of Santa Catarina.