// Interview: Francisco Alberto Caricati

Director General of the Penitentiary Department of the State of Paraná, Brazil

JT: What are the main challenges facing the Paraná correctional system and what measures are being taken to address them?

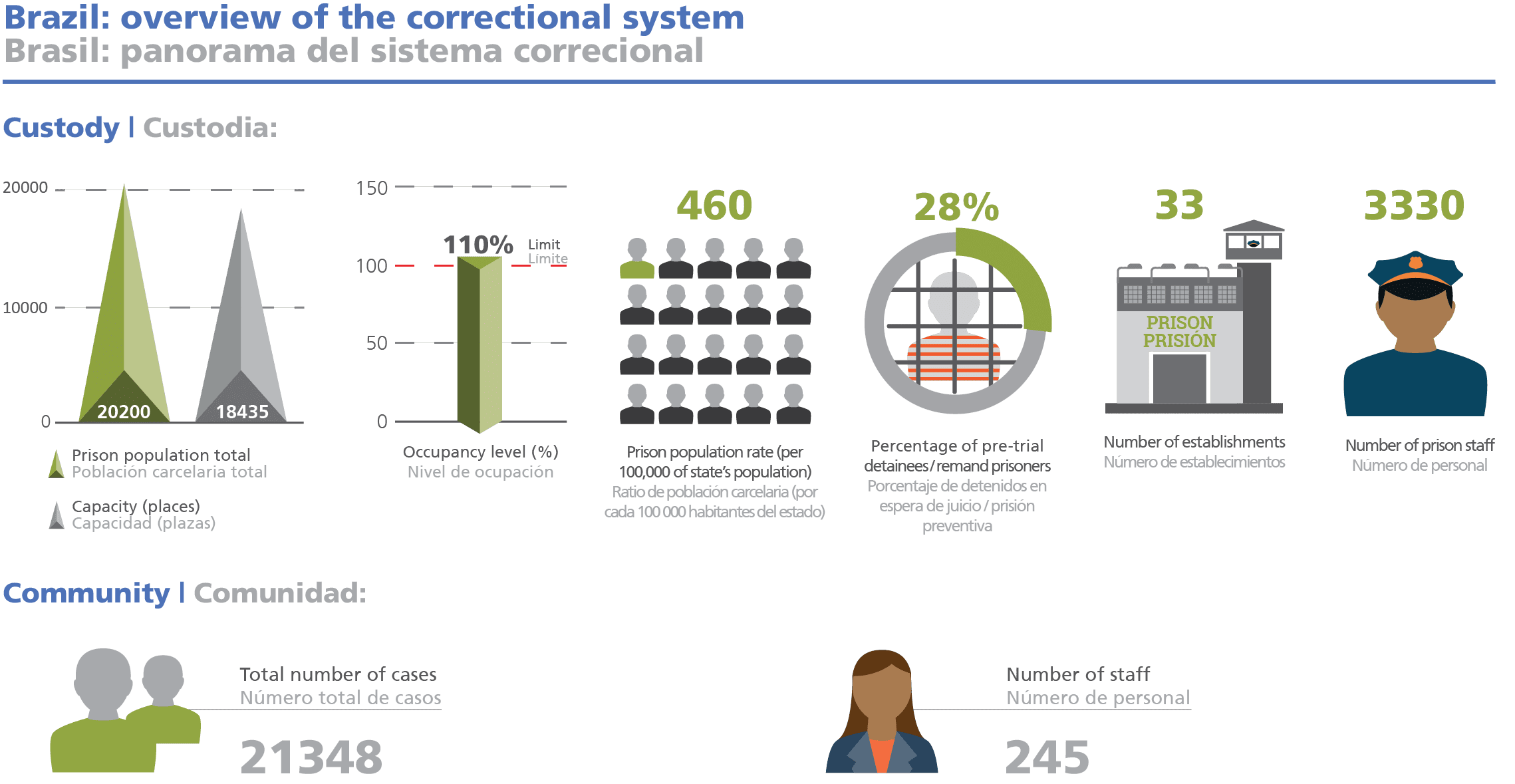

FAC: Overcrowding in prisons is a reality across the country. To solve this situation in Paraná, we have fourteen construction projects and expansions of prison units in progress, which will generate about seven thousand new places in the prison system.

In addition, we have six new Custody Houses projects to house provisional prisoners, which will generate another 3,000 vacancies. Creating these vacancies is fundamental so that we can put an end to the situation of prisoners being held in police stations in the State.

We are also investing in technologies such as increased electronic monitoring and automation of prison units – which provide more security for workers in the penitentiary system – and a new system for identifying and monitoring prison management. Lastly, we are committed to increasing the programmes that allow for the rehabilitation of individuals deprived of their liberty.

To solve the overcrowding, we have fourteen construction projects and expansions of prison units in progress, which will generate about 7,000 new places.

JT: The State of Paraná has a Criminological Observation and Screening Centre. Could you please explain to us what this penal institution is and how important it is for the operation of the penitentiary system?

FAC: Today, the Criminological Observation and Screening Centre operates in the same area as the Custody House of Piraquara, an entrance unit of the prison system in the region of Curitiba.

The establishment receives inmates from police stations who are identified and referred to other prison units. Throughout the State, in each regional department of the Penitentiary Department (DEPEN), there is a unit responsible for carrying out this identification and classification work.

Its role is of the utmost importance since it is in this establishment that the prisoners are classified according to the type of crime, procedural situation and whether or not they are involved with criminal gangs, among others, in order to be referred to a prison unit that is suitable for their profile.

JT: Regarding non-custodial criminal enforcement, there’s a Patronage Programme (Programme for the Municipalisation of Non-custodial Criminal enforcement), which advocates the shared responsibility of public authorities regarding the rehabilitation of offenders.

What are these Patronages, what is their state of development and what impact do they have in practice?

FAC: The Patronages attend to those who leave the penitentiary system and also those receiving alternative penalties and sentences. They have two roles: to monitor and rehabilitate those attended to.

Created in 2013, the Patronage Programme is present in all regions of the State, through agreements with municipalities and universities. This agreement includes the training of multidisciplinary teams that allow attendees to have access to formal education, professional qualifications, digital inclusion and the job market.

Through the programme, psychosocial care and legal assistance, as well as basic training and professional qualifications, are offered to attendees and their families. This work is fundamental for the follow-up of the ex-convict and the fulfilment of the sentence so that we can actually achieve rehabilitation and, consequently, a reduction in recidivism.

Electronic monitoring is an alternative to prison overcrowding and the cost of maintaining prisoners, while still saving individuals from the effects of incarceration and promoting rehabilitation.

JT: Since 2010, new laws have been created to streamline the use of electronic monitoring. What is the state of play regarding electronic monitoring and what results has it shown?

FAC: In Paraná, electronic monitoring began in October 2014. Currently, 7,000 cases are monitored across the state. It is the most advanced technology we have available today in the market in terms of surveillance. Individuals are monitored 24 hours a day by trained prison officers who work in the DEPEN Monitoring Centre and also in the Integrated Command and Control Centre (ICCC) of the Secretariat of Public Security and Prison Administration.

The individual who is allowed to wear the electronic anklet is monitored day and night and cannot take off the equipment, neither to sleep nor to shower. They are also forbidden from exceeding a restricted area determined by the Court, and if they do, the GPS device vibrates, an alarm goes off and the offence is reported to the monitoring centre.

Whenever the anklet stops working, runs out of battery or is broken, a notification is sent out via the system to the DEPEN Electronic Monitoring Centre and to the ICCC in real time. The judiciary is informed of the offence immediately. The judge then analyses the situation and, depending on the case, can even decide to go back on the regime and issue an arrest warrant to the recipient.

The criteria are set by the judiciary: it is the judge who is responsible for assessing whether or not the person can receive electronic monitoring, and it is also the judge who decides what the monitored individual can and cannot do (time and place).

In general, electronic monitoring is used in the case of provisional prisoners who do not fulfil requirements leading to pre-trial detention, house arrest, or even the harmonised semi-open regime with house arrest and release for working and studying.

In Paraná, there are a predominant number of harmonised semi-open and provisional prisoners. Electronic monitoring is an alternative to prison overcrowding and the cost of maintaining prisoners, while still saving individuals from the effects of incarceration and promoting rehabilitation.

The future lies in projects that rescue citizenship and offer opportunities for professional and educational qualifications (…) projects that offer a new horizon for the incarcerated.

JT: Recently, the plan to give all state prisons the opportunity to carry out videoconference hearings.

How many virtual hearings are already carried out and what impact does the use of technology have on the Penitentiary Department of Paraná?

FAC: Carrying out hearings via video conference is a very recent phenomenon in Paraná. In Curitiba and the Metropolitan Region, this practice began just over a year ago. Inside the state, it began in May 2018.

The penitentiary department of Paraná is investing in this technology because it understands that this is a tool that reduces the risks of transporting prisoners and reduces the number of security professionals and vehicles involved in the process. In other words, it saves time and public resources. The number of video conference hearings has been increasing, with weekly records in the Curitiba region, where the technology has been available for the longest time. In Cascavel, there are about 3-4 hearings per week.

DEPEN provides the structure, but the decision of whether or not to incorporate the technology depends on each court responsible for assessing the case. We have an agreement with the Court of Justice of the State of Paraná which also supports the practice, so I believe it is likely that the use of this technological resource will increase.

JT: How do you see the future of the Brazilian correctional system in general, and that of the State of Paraná in particular?

FAC: I believe that the future lies in the recovery of those deprived of their liberty by means of projects that rescue citizenship and offer opportunities for professional and educational qualifications, that is, projects that offer a new horizon for the incarcerated.

Prison alone is not capable of recovering anyone; you need to offer different means of change. In Paraná, we aim for the involvement of all sectors of society so that, together, we can change the reality of the prison system.

Today we have community offices that follow up, outside the prison, individuals under electronic monitoring, as well as the implementation of the progression units that work hard with inmates of the closed regime who are about to be released, preparing them for going back into society. All of these actions require the participation and involvement of everyone so that they can actually bring about effective results.

//

Francisco Caricati’s career has been made in the Civil Police where, during his almost 30 years as a civil servant, he has held various positions in various divisions including at the Special Police Operations Center Branch, the Stealing and Theft Office, or the Economic Crimes Unit. He was also the director of the Department of Intelligence of the State of Paraná. Before assuming the Paraná Penitentiary Department – in May of 2018 – he was head of the Police Division of the Capital.