Interview

Ricardo Pérez Manrique

Judge, President of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights

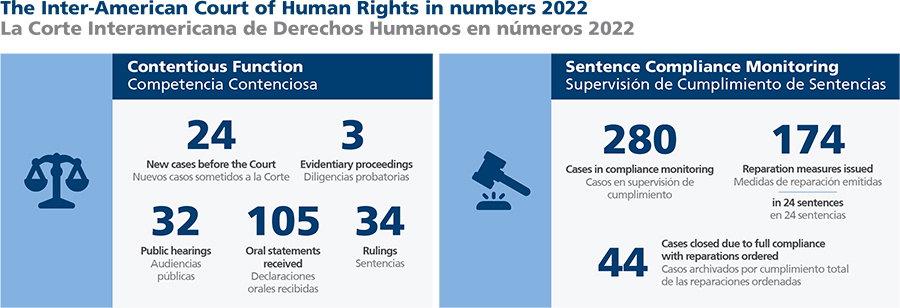

The Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) is an autonomous judicial institution created to protect and promote human rights. It is one of three regional courts for the protection of human rights, together with the European Court of Human Rights and the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights.

The IACHR is composed of seven Judges¹, nationals of the Member States of the Organisation of American States (OAS), elected by the Member States at the OAS General Assembly.

The purpose of the IACHR is to interpret and apply the American Convention, adopted in 1969 by an assembly of countries of the region².

In addition to promoting human rights through its contentious and advisory functions and the power to issue provisional measures, the Court plays an essential role in institutional strengthening and professional training. The seat of the Inter-American Court is located in San José, Costa Rica.

What are the main challenges facing the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in its work to protect human rights in the region?

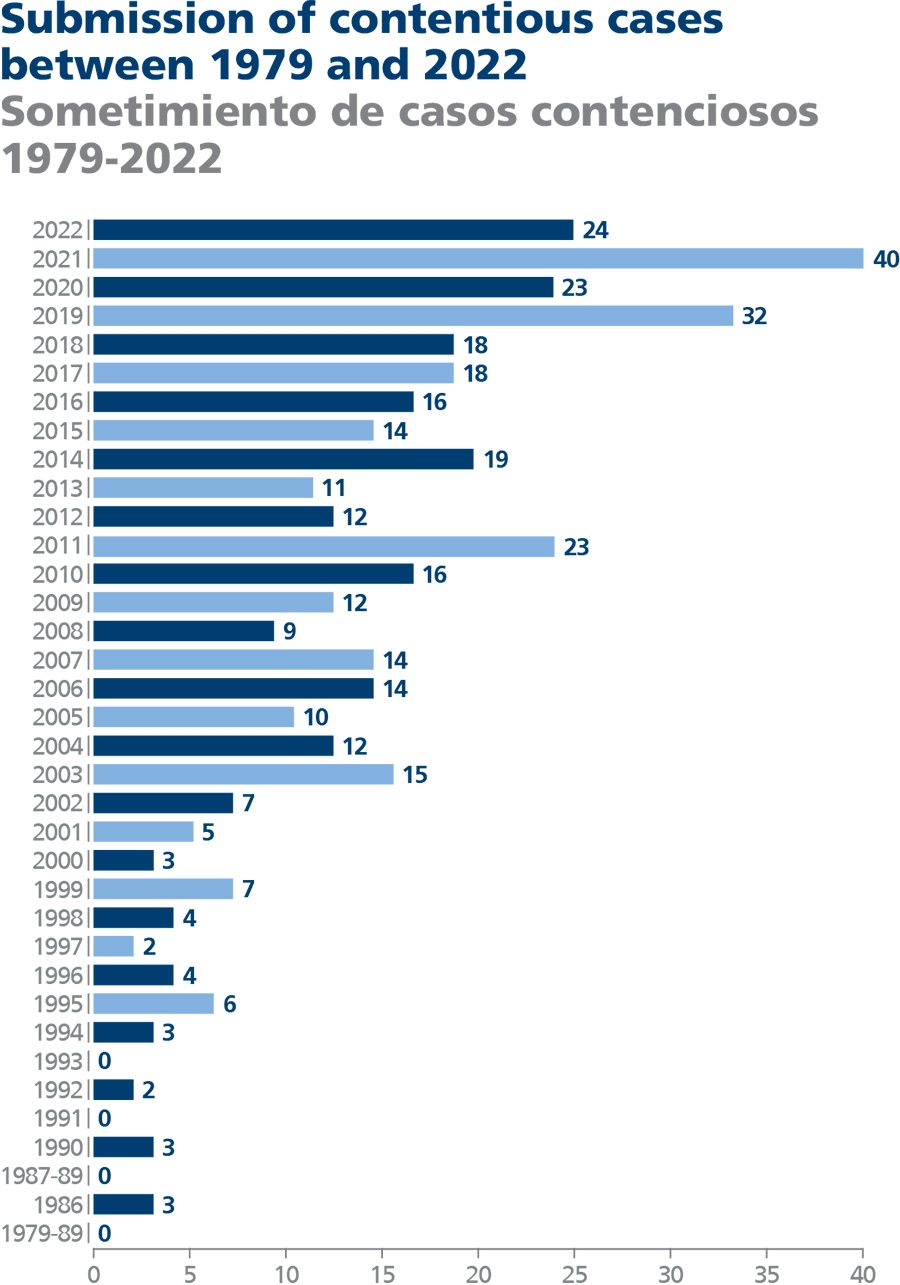

RPM: The Inter-American Court of Human Rights will be 45 years old in 2023. In those decades of existence, a number of significant events have taken place that, from a historical point of view, shaped the political, institutional and social reality of the region.

We should bear in mind that the Court began to work amid the Cold War and that its first rulings had to do with internal confrontations and civil wars in Central America. And today, we are witnessing a turbulent situation in the continent, with risks to democracy, among others.

Throughout its history, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights has been an instance in which people who found their rights infringed in their states could turn to the Inter-American system, and ultimately to the Court, in order to enforce them.

In this process of historical development, the Court consolidated its jurisprudence on a variety of aspects, some of which were unexplored at the universal level. For example, the first judgments in the Honduran cases (Velásquez Rodríguez v. Honduras is a famous one) are linked to the forced disappearance of persons. And the Court said that if such conditions exist and there is a repeated and permanent refusal on the part of the State to provide information to the relatives, and the situation

continues indefinitely over time, we are dealing with a phenomenon of violation of several rights.

Since then, there have been an extensive number of jurisprudential developments, for example, all the ways in which the Court has been interpreting article 13 on freedom of expression, with judgments – including very recent ones – such as that of the journalist Jineth Bedoya Lima and another vs. Colombia3 on violence against journalists or Palacio Urrutia and others vs Ecuador4.

In short, the Court has been following the different political moments in the region, adopting decisions to safeguard human rights and applying the American Convention.

I believe that – and I said this when I assumed the presidency – the great challenge for the Court is to maintain the level of acceptance of its judgments, maintain its prestige as a court and give it strength. That is why we have worked hard, from the internal institutional point of view, to make the Court more robust, precisely to face the very complicated and challenging situations arising from the enforcement of human rights in the region.

We must develop better conditions to ensure that human rights are respected, and, above all, the objective is that the measures taken by the Court can be helpful and effective and that they have a functional role in preventing human rights violations.

How are cooperation and collaboration between OAS member states being strengthened, regarding human rights protection?

RPM: One of the things we set out to do when we took over the presidency of the Court is to stand as a court that functions in what is called open justice, that is absolutely accessible to all people, and whose decisions are recognised.

Our objective is an open Court that dialogues with States and not only in formal instances (the Court appears before the Permanent Assembly of the OAS, with its annual report and then before the General Assembly, where it also makes its annual report), but we are committed to a strategy of expanding the Court’s presence in the Member States, which has increased.

In 2022, the Court visited Uruguay and Brazil, at the invitation of their governments. We have held sessions there with great success.

When we are in a country, the Court holds seminars, meetings with the press and dialogues with States, their governments and civil society.

In addition, we have implemented a system of increased presence in the territories which, for example, we started last year with a supervision effort. Three judges went to Panama, to the Darien jungle, to verify compliance with a precautionary measure of provisional detention that we had imposed to prevent COVID-19 among migrants. Afterwards, judges held hearings in several countries, such as Argentina and Mexico, among others.

Being in continuous dialogue with societies and countries is how we understand that we can improve the reception of our decisions and work.

It is precisely in this line of horizontal communication, which transcends formal modes – which, of course, we respect and strictly comply with – that in 2022 the Court has held meetings with journalists in seventeen countries across the region.

At these meetings, we discussed the jurisprudence of the Court, but we also received the concerns and assessed the situation of journalists. There were seventeen such meetings, from Mexico to Argentina, including practically all the countries of Central and South America, and Trinidad and Tobago.

So, these are the connections that we have been deepening since the start of my presidency. And they are producing results: people know and come to the Court, people dialogue with the Court and we are enriched by this dialogue and strengthened from the institutional point of view.

And that is the objective that every person in charge of an organ such as this must carry forward, with the support of their colleagues.

In this line of our work, this year, we are launching an online television channel of the Inter-American Court. This television channel will have, on the one hand, the purpose of disseminating the Court’s activities and, on the other, it will be associated with training programmes.

To what extent are dialogue and training important in the judicial systems of the region?

RPM: I have been a judge in Uruguay for thirty years, where I also became president of the Supreme Court of Justice and where I had a very intense work within the framework of the Ibero-American Judicial Summit, which brings together the judiciaries not only of Latin American countries, but also of Spain, Portugal and Andorra.

In that sense, I have a deep knowledge of the judiciaries in the region. I became permanent secretary of the Ibero-American Judicial Summit, and I follow, with great attention, the evolution and changes at the level of the judicial systems in the region.

What must be admitted is that – and obviously, I am going to talk about concrete cases – one of the central elements of this whole wave of left and right-wing populism in Latin America today is the postulation that there is only one truth in the management of society and the conduct of political affairs. In this framework, the judiciary, which seeks to apply the law and enforce human rights, sometimes becomes a nuisance.

So, their answer is, as one author commented, to try to colonise these judicial systems so that they do not continue to be a problem, an opposition to the development of certain policies. We are committed to dialogue and supporting judicial systems. We have said that judicial independence is a crucial for the jurisprudence of the Court and for the existence of the democratic rule of law.

It is, therefore, an area in which we have worked all our lives, in which we remain committed and in which the Court is constantly developing its jurisprudence on.

What has been the progress and impact of the implementation of alternative measures to imprisonment in the region?

RPM: Unfortunately, the prison situation in the region is critical due to the inflation of the penal response and, above all, the penal response through deprivation of liberty, which is still the most common penalty.

The Court has very clear jurisprudence that preventive measures of deprivation of liberty are only acceptable based on a procedural basis, such as the risk of absconding or the risk of preventing a proper investigation of the crime. Otherwise, a preventive measure of deprivation of liberty should not be applied.

However, we know that some countries abuse pretrial detention and this generates a heavy recourse to prison services. If it is not adequately responded to, because it is impossible to do so, overcrowding occurs because the number of people deprived of their liberty is constantly growing. In these scenarios, prisons do not fulfil any rehabilitation purpose whatsoever, and situations of very severe human rights violations are generated.

In the 1990s, I worked a lot on adolescent/juvenile criminal justice and was invited to the state of Minnesota in the USA. There I heard a presentation, which lasted no more than half an hour, in which all the advantages of alternative measures to imprisonment versus custodial measures were graphically demonstrated. Basically, alternative measures are less costly for society. Although the most important issue is not cost, it must be said: it costs less to apply non-custodial measures properly than to imprison people. But the most important thing is that they are the actual rehabilitation measures – the ones that allow the person, through appropriate follow-up carried out outside the framework of deprivation of liberty – to have a much better chance of social reintegration. This is not achieved by isolating the person, taking them out of society and returning them, several years later, full of resentment and carrying on their shoulders several violations of their fundamental rights.

Moreover, I believe that among the alternative measures to imprisonment, we should consider measures that directly avoid recourse to criminal proceedings. I am convinced that mediation in criminal matters should be promoted. However, in most countries in the region, mediation in criminal matters is a bad word, because a whole cultural issue is not being addressed.

The criminal route is not the only response to the offence derived from a crime. And here, we must think about how criminal law – which, in itself, is an expression of institutional violence, for which there are all the guarantees and all the limitations – can adopt alternatives that are not extreme and that can lead to the resolution of conflicts between people. This requires work on cultural change.

What is becoming evident in some countries is that the policies of increasing the number of crimes and increasing sentences increase the number of people in prison. And these become a breeding ground for human rights violations: among the people deprived of their liberty, and from the actions of the authorities to maintain order. Moreover, they become centres of crime because organised gangs take over prisons. The facilities are used for crime, becoming a centre for exchanging illegal services.

We are committed to dialogue and supporting judicial systems. We have said that judicial independence is a crucial for the jurisprudence of the Court and for the existence of the democratic rule of law.

How is accessibility to the justice system being improved for the most vulnerable people in Latin America and the Caribbean?

RPM: I think a lot of progress has been made in some countries, but not so much in others. Let’s bear in mind that the region, in addition to all the political difficulties we know about, has fundamental structural problems.

There is a phenomenon that I call the “overlapping of civilisations”, because in the region we have countries in which we have the broadest level of development, of the first world, intermediate situations, and other countries in which there is permanent tension between groups whose objective is the indiscriminate exploitation of natural resources and others that live off these natural resources but do not have the conditions to defend them.

So, there we have a series of structural issues that lead to the need for a policy of access to justice, a national policy, and why not think of a shared policy between states on access to justice?

Regarding Inter-American Justice: in the Inter-American system, unlike the European system, where any citizen can access the European Court of Human Rights directly, with their application, in the Inter-American system, one must first go, as in the past in Europe, to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights.

This is the body that processes the case, tries to resolve it amicably, and, when it fails to do so, brings it before the Court to process it as a dispute between the victim and the State. I think that people should have more direct access to the Court – it should be discussed, but I see this as a challenge for the system as well.

JT: In the opening message of the Inter-American Judicial Year 2022, Your Honour issued a warning: “Artificial intelligence, like any tool, has a neutral character, but it can lead to transgressions or violations of human rights”.

With the increasing use of artificial intelligence and related technologies in justice systems, what challenges will such actions pose for protecting human rights?

RPM: In that sense, we live in an exciting time, but it is also a time of enormous challenges. The development of technology cannot be in the hands of engineers alone. It must also involve legal actors, because technology is increasingly interfering with people’s rights.

When we see that, for example, people born after 1995 are considered to have no privacy because all their relevant data is in the hands of third parties, we face problems that affect people’s rights. We see how the use of social networks, in a way, degrades democratic debate and generates a situation in which it is possible to influence electoral processes with the use of technology.

The Court is very attentive to this issue so that we are even thinking of initiating official discussions, with workshops on artificial intelligence, even though we have not had any cases yet. It is a situation that should keep all of us in the Court very attentive.

I think that the United Nations principle regarding [social] networks can be extended: the rules of law that regulate relations between people in the real world are the same that should regulate relations between people in the virtual world.

And this virtual world is severely affected by the existence of big players that transcend states, through their power and the amount of information that they handle, that there is no adequate scope in which they can be called to account when they commit abuse or violation of the rights of others. So, I believe that deepening education and training of people are the main challenges of the moment, intending to achieve a more humane and sustainable world.

In terms of using technology and artificial intelligence in the courts’ decision-making process, we are also facing a big challenge. I think they can play a support role, there are very interesting upcoming technologies. For example, we know how much work it meant to us, a few years ago, to search for sources, from a legal, doctrinal, documentary and other points of view, before taking a decision.

With technologies and artificial intelligence, time is saved in searching for the appropriate sources for the specific case because there is an intelligent search for resources to adopt a decision, which seems to me to be a very important advance. However, we must never create an automatism that considers only the elements that artificial intelligence gives us, or the reports it produces as valid, but we must be careful of the risks.

Sometimes, artificial intelligence can be discriminatory. For example, in a country where there is discrimination against a certain racial sector and where there is a significant number of people of African descent in prison – because, depending on their discrimination and their social situation, they are accused of crimes – artificial intelligence will make a literal reading since there is a social sector that is predominantly the perpetrator of criminal acts. And there we run the risk of perpetuating discrimination.

We need to be alert to these risks, and I think, I repeat, that we have to create mechanisms that seek, first of all through warning and prevention, to avoid using these resources in a way that harms people’s rights.

¹ The Court is currently composed of Judge Ricardo C. Pérez Manrique, President (Uruguay); Judge Eduardo Ferrer Mac-Gregor Poisot, Vice-President (Mexico); Judge Humberto Antonio Sierra Porto (Colombia); Judge Nancy Hernández López (Costa Rica); Judge Verónica Gómez (Argentina); Judge Patricia Pérez Goldberg (Chile); and Judge Rodrigo Mudrovitsch (Brazil).

² States that have ratified the American Convention: Argentina, Barbados, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Grenada, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Suriname and Uruguay.

3 In its Judgment of the Case of Bedoya Lima et al. v. Colombia, Inter Colombia, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights held the State of Colombia internationally responsible for violating the rights to personal integrity, personal liberty, honour, dignity and freedom of expression to the detriment of journalist Jineth Bedoya Lima, as a result of the events that occurred on 25 May 2000, when Ms. Bedoya was intercepted and kidnapped at the gates of La Modelo Prison by paramilitaries and subjected to humiliating and extremely violent treatment, during which she suffered severe verbal, physical and sexual aggression. The Court noted that there were “serious, precise and concordant indications” of State involvement in these events.

4 In the Judgment of the Case of Palacio Urrutia et al. v. Ecuador, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights declared the international responsibility of the State of Ecuador for violating the rights to freedom of expression, the principle of legality, movement and residence, employment stability, judicial guarantees and judicial protection, and the duty to adopt provisions of domestic law, to the detriment of Emilio Palacio Urrutia, Nicolás Pérez Lappenti, César Enrique Pérez Barriga and Carlos Eduardo Pérez Barriga.

Ricardo Pérez Manrique

Judge, President of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights

Ricardo Pérez Manrique has been elected president of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights for 2022 and 2023. With a solid academic background, he graduated as a Doctor in Law and Social Sciences in 1973 from the University of La República (Uruguay) and revalidated his degree in 1989 at the University of Buenos Aires. Judge Manrique has held several important positions in the justice system of his native Uruguay, including his distinguished career as a minister of the Supreme Court of Justice, between 2012 and 2017, and the position of president of the same court in 2016.