// Interview: Ángel Yuste Castillejo

Secretary General of Penitentiary Institutions, Spain

JT: What are the main differences between the penitentiary system that you ran between 1996 and 2004 and the current one?

AYC: Important changes took place, although our Penitentiary Law (of 1979) has hardly had small reforms in its articles (1). In recent decades, the various legal reforms in Spain directly or indirectly affected the prison legal relationship, and also have an impact on the way in which the sentence of imprisonment is served.

The most important was the entry into force of the new Criminal Code, in 1996 – the so-called “Criminal Code of Democracy” (Organic Law 10/1995 of November 23rd) – which, since then, has already had twenty-six reforms (2). The latest reform, in 2015, introduced a new punitive modality in the legal system (the so-called “revisable permanent imprisonment”) and modified the nature of conditional release, transforming it into a modality of suspension of the sentence.

In addition, other legal reforms were carried out in various areas (labour, health, education, budgetary, administrative, public function, immigration, protection of the victim and international judicial cooperation). Many of these reforms occurred because of the need to incorporate the regulations established in the Framework Decisions of the European Union into our internal legal order.

Moreover, the profile of the prison population has also changed – essentially due to the arising of new criminal forms such as “political corruption” and jihadist terrorism.

The technological advances also brought significant changes, as well as the construction of new penitentiary infrastructures with a versatile functional model introduced by the Penitentiary Regulation of 1996 (Royal Decree 190/96 of February 9).

All in all, these are changes that have led to a process of updating the penitentiary legislation that has contributed decisively to the modernisation of the system.

Many of the reforms occurred due to the need to incorporate the Framework Decisions of the European Union into our legal system.

JT: Despite the investments made in the Spanish penitentiary system in recent years, perhaps among the most difficult challenges is still the lack of professionals, which tends to produce an increase in social conflict within penitentiaries.

In fact, the figures show that between 2011 and 2016 more than 2.200 attacks on prison officers occurred. At the same time, Unions say there are 3.500 new places to be filled over the next four years, in addition to the annual replacement places (Source: Newspaper “El País”, August 10th and 29th, 2017).

Is this true? What are the problems of the system in this matter and what measures are on your plans to solve them?

AYC: This information is only partially true. It is frequently tried to argue about a climate of conflict in the penitentiary centres, but we have highly qualified professionals, a modern structure that allows an adequate separation of the inmates, a clear and precise procedure that regulates the security measures to face conflicting situations, as well as an occupation ratio that has been improving and consolidating over the time.

Actually, between 2011 and 2016 there have been 2.207 attacks on officers, of which 1.193 without injuries. The prison environment tends to be conflictive and facilitates the emergence of aggressive behaviour by inmates; however, the figures of assaults on officers show a downward trend, which allows an advantageous comparison with previous years and, especially, with countries like France or the United Kingdom.

In the year 2017 (until the end of November) we had 269 assaults, 96 of them without injuries. However, in 2016, a “Specific Protocol to Prevent Assaults in the Penitentiary Area” was developed, whose specific objectives are to prevent potentially conflicting situations that may generate aggressions against public prison employees; establish preventive measures and strategies that include guidelines for clear and effective actions in the face of violent incidents and aggressions; ensure the safety and health of prison employees, as well as support those who have been victims of assaults, when they were on duty.

More specifically, measures have been developed that aimed at improving the knowledge of inmates by the officers, updating and reviewing the means and techniques of personal protection, and strengthening intervention and treatment programmes aimed at the most quarrelsome inmates.

A new Violent Behavior Intervention Programme (PICOVI) was also introduced with the aim of helping the inmates to recognise their behaviour and motivate them to change, promoting a lifestyle and values adapted to the norms of coexistence and pro-social behaviour.

As for the lack of personnel, it is true that there have been years of cost containment due to the economic crisis. This situation has forced to establish strategies of sustainability of the staff that, at the present time, have been overcome. In recent years, our public employment offers have exceeded the replacement rate, and in 2017, it stood at 196%. Thus, we observe that if in the years 2010-2011 the job offer was of 351 jobs; in 2016-2017 it totalled 1.374.

Adding to the above, the decrease in the prison population has meant the reduction of the ratios of inmates/officers: in 2008 the ratio was 2,7, while in November 2017 it was 2,1. This is an indicator that we intend to improve even more in the future.

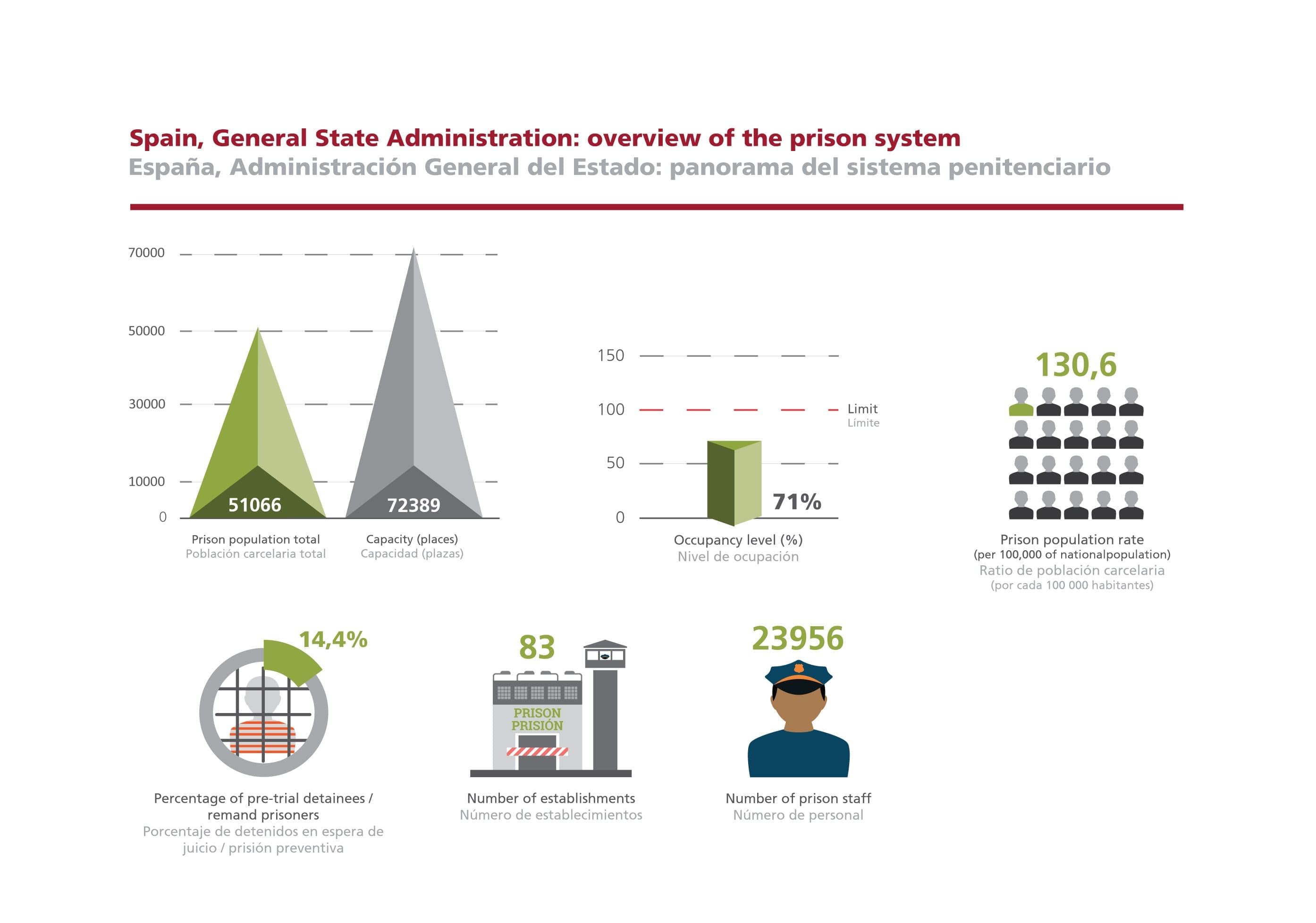

JT: Although prison population rate of Spain has been decreasing in recent years, it still has one of the highest rates in Southern Europe (130 per 100.000 people).

What solutions are there to reduce this rate below 100, so that Spain approaches countries such as Germany, Denmark, or Belgium?

AYC: Since 2009, we have witnessed a downward trend: we have gone from a figure of 76.000 inmates, as of December 31st of that year, to one of 59.500, at the end of 2017.

With regard to the data of the centres that are in charge of this General Secretariat – that is, excluding Catalonia – that figure has gone from 65.548 to the current one (day 8, December 2017) of 51.066. That is, 14.482 inmates less.

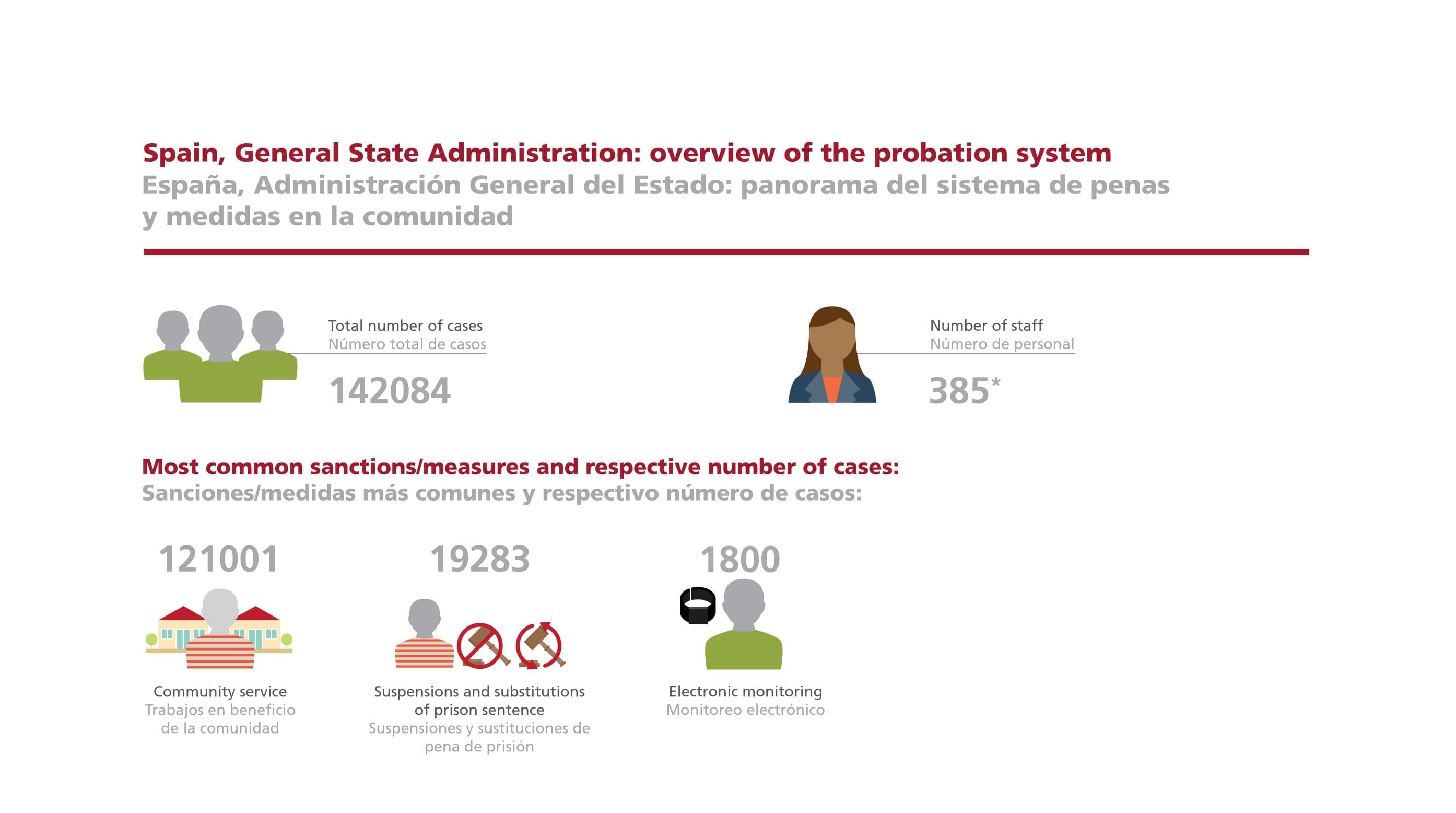

To continue maintaining this trend, we want to promote the effective management of alternatives to incarceration, particularly concerning work for the benefit of the community, suspension of sentences and substitutions.

Besides that, we are also promoting the transfer of convicted persons to their countries of origin or residence in the European Union community sphere, through the procedure introduced by Law 23/2014, which transposed the Framework Decision 2008/2009 into the Spanish internal law.

JT: Spain is the European country with the highest rate of imprisoned women (7.5% of the population in prison, or about 4000 women) (Source: PrisonStudies.org).

Is this reality a concern for you? How do your institutions adapt to women deprived of liberty, and what should be done to reduce this inflated rate of women prisoners?

AYC: It is true that the female prisoner population rate is higher than that of neighboring countries, but the justification, among other reasons, is found in the large number of foreign women serving sentences for drug dealing. If we would consider only the indigenous female population, the figure would be around 5,4%.

Women prisoners all the attention that the male inmate population can have: they participate in the same intervention and treatment programmes and have access to the same type of training and occupational activities, without prejudice to carrying out other specific activities that are part of the Sermujer.es Programme.

Since 2009, a programme has been implemented with specific and transversal actions aimed at overcoming the factors of special vulnerability that have influenced the immersion of women in criminal activity; eradicate gender-based discrimination factors within the prison; comprehensive attention to the needs of imprisoned women; favour the eradication of gender violence especially the psychical, medical, addictions, etc., associated with the high prevalence of episodes of abuse and mistreatment in their personal history. All the information regarding this topic is available on our website.

Since 2014 that we have been monitoring the jihadist phenomenon in prison.

JT: The issue of radicalisation in prisons is on the agenda and prisons can be an appropriate habitat for this phenomenon.

Many prison officers speak of lack of resources, lack of training and lack of coordination to implement measures to address the problem. (Source: El Confidencial, September 10th, 2017).

What’s your opinion on this information and what are the challenges regarding the issue of radicalisation in Spanish prisons?

AYC: Since July 2014 that we have been monitoring the jihadist phenomenon in prison through two mechanisms of action.

At first, a plan was developed for the prevention and monitoring of those inmates who are linked or susceptible to being linked to the jihadist cause, for which a protocol was established through internal regulations (Instruction I-8/2014) – a Protocol for the Detection of the Jihadist Phenomenon.

Through observation and exchange of information, this Protocol has made it possible to establish a categorisation of jihadist prisoners in three monitoring groups (Group A: Pre-trial detainees or prisoners for acts related to the so-called Islamic terrorism; Group B: Inmates framed in an attitude of recruiting and proselytising leadership that facilitates the development of extremist and radical attitudes among the inmate population and / or who carry out a mission of indoctrination and dissemination of radical ideas about the rest of the inmates – activities of pressure and coercion, that is, they are the “recruiters”; Group C: Inmates who show signs of Islamist fanaticism, radicalised or in the process of extremist radicalisation; they show attitudes of contempt towards other non-Muslim, or even towards Muslim inmates, who do not follow their precepts).

According to this categorisation, these inmates have been distributed among 53 different prisons. This programme has allowed us to detect, monitor and control the phenomenon.

In terms of detection, there has been an increase in the number of inmates who are monitored because of their possible connection with the jihadist cause, which has increased from 87 in 2014 to 280 in November 2017. In terms of profile, the most common is Group A (with 153 inmates), followed by C (87 cases) and finally B, where 40 inmates are detected.

In terms of control, the regimental incidents carried out by these inmates decreased, and the number of those who participated in them is scarce, which is not the case in other neighboring countries. It is even necessary to emphasise that, in some cases, inmates of jihadist profile have collaborated with the officers to avoid some type of incident carried out by other inmates.

In a second phase, once this Protocol was consolidated, a Programme of Intervention and Voluntary Treatment for the Jihadist Inmates (Instruction I-02/2016) has been established, in order to offer them help to overcome the approaches that strengthen their ideology, trying to return them to society with the ability and willingness to respect criminal law, and also the values of a social and democratic State of law.

This Programme responds to the standards of the strategic action framework against terrorism of the Radicalisation Awareness Network (RAN), of the European Commission.

JT: As far as the future is concerned, how do you think the Spanish system will evolve?

AYC: The evolution of the penitentiary system will follow the one of the criminal legislation. This is marked – with the entry into force of a new Penal Code in 1996 – by an increasingly accentuated tendency to increase alternative measures to incarceration, which undoubtedly are at the base of the decline of the prison population. These alternatives reach figures close to 140.000 resolutions per year.

We must also consider the progress of new technologies. They allow that, in many cases, the penalty of deprivation of liberty can evolve towards forms of limitation of freedom that are less harmful for the convicts and their families, ways more suited to the correction and reeducation of the sentence.

//

Ángel Yuste Castillejo has a degree in Law and a diploma in Criminology from the Complutense University of Madrid and holds the position of General Secretary of Penitentiary Institutions since January 2012. He previously held the position of Director General of Penitentiary Institutions, between 1996 and 2004. Jurist of the Technical Body of Penitentiary Institutions, he was assigned as an official in several prisons in the country and in the Central Services.

Notes:

(1) As have been carried out by the Organic Law (OL) 13/1995, of Dec. 18th, in the articles 29.2 (rest period for pregnant women that equalled the rest of women) and 38.2 (which reduces the age of the children to 3 years), the OL 5/2003, of May 27th, in article 76; 2.h), which introduces the figure of the Central Judge of Penitentiary Monitoring, the OL 6/2003, of June 30th, in article 56 (eLearning through the UNED) and OL 7/2003, of June 30th, article 72 (5 and 6), the most important of the reforms that the penitentiary law has undoubtedly suffered to the date, which regulates, for the first time in the scope of custodial sentences enforcement, the requirement to repair the material damage and, in some cases, moral damage caused the victim, to accede to the regime of semi-liberty that supposes the 3rd degree of penitentiary classification

(2) Three reforms of enormous importance have been those carried out by the Organic Laws 15/2003, 5/2010 and 1/2015