Article

It’s easy to take health for granted. Before spending two weeks working alongside Health through Walls in Maputo, Mozambique, I certainly did. As someone who moved from Portugal to Toronto and now studies global health and political science, I believed I had a clear understanding of health disparities. Yet nothing prepared me for the reality inside Mozambique’s prisons. These institutions, relics of the colonial era, are crumbling and overcrowded. Dozens of men lined up in the courtyard for a full health screening, for many the first in their lives, with their eyes fixed on the mobile X-ray unit and the staff ready to engage them. Some were curious, others wary, many simply tired, but all were grateful that someone cared about their health. Many told stories of never having such opportunities in their lives outside prison, and of never being screened upon arrival. In that moment, I understood: behind these walls, healthcare is not guaranteed. It is a scarce and fragile opportunity.

I came to Maputo to join a two-week health blitz with Health through Walls, an international non-profit dedicated to addressing the health needs of incarcerated populations in resource-limited settings. Founded on the principle that prison health is public health, the organization works to reduce the spread of infectious diseases, improve living conditions, and build capacity within prison systems to ensure sustainability. My role during this health blitz, conducted in collaboration with SERNAP (Serviço Nacional Penitenciário) and Emory University, involved supporting screenings for infectious diseases like tuberculosis (TB) using artificial intelligence technology by Qure.ai.

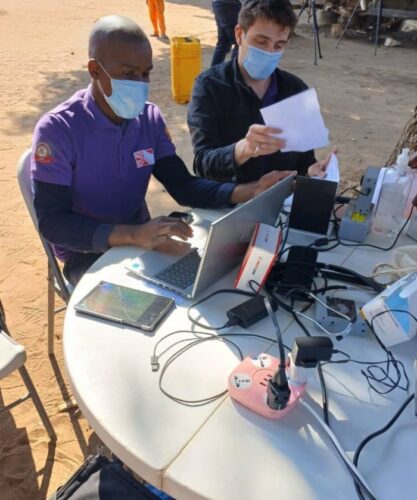

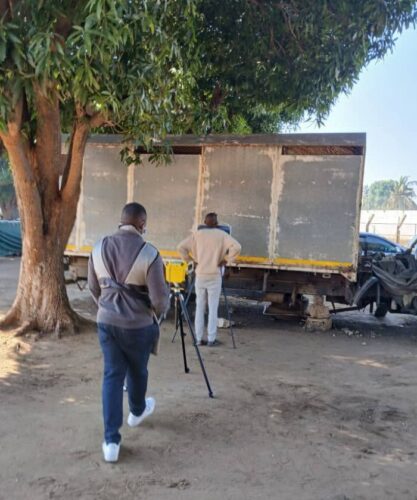

This intervention used AI-powered digital chest X-ray technology (DCXR-CAD) to detect TB and other lung diseases with speed and accuracy. Qure.ai’s software could interpret X-rays in under a minute, assign a TB abnormality score, and highlight suspicious areas for review. This method was combined with symptom screening and confirmatory GeneXpert testing.

The setup followed a flow of stations, each one building on the last. Registration came first, where each person was identified and provided a form so results could be matched and follow-up ensured. Intake surveys gathered structured information about age, place of origin, length of stay, TB risk factors, symptoms, and prior treatment. Next was pre-test counselling followed by HIV testing, and then a short mental health survey to identify urgent needs such as anxiety, depression. The core was the chest X-ray with AI triage. Each image was analyzed instantly, generating a TB score and a radiograph highlighted with suspicious spots. Finally, a clinical consultation ensured that patients saw a physician, who reviewed the results, confirmed the diagnoses, and initiated treatment or TB preventive therapy (TPT). In cases of abnormality, sputum samples were tested on-site with the GeneXpert MTB/RIF Ultra system to detect TB and rifampicin resistance. Patients also received advice on skin conditions, nutrition, and follow-up care.

I rotated through these stations during the two weeks, handling registration, conducting surveys, assisting with X-ray triage, and supporting clinicians as needed. I worked alongside physicians, nurses, epidemiologists, radiographers, data officers, and Mozambican co-volunteers who kept the system moving with patience and professionalism. Speaking Portuguese was an asset, allowing me to talk with local staff and detainees, to explain, listen, and translate when needed.

The conditions inside Mozambique’s prisons were challenging, despite the best efforts of the staff and detainees in the facilities. Cells were severely overcrowded. Many detainees slept in hallways on concrete floors, leading to scabies and other skin diseases. Hygiene facilities were rudimentary. Detainees used makeshift plugs of cloth and plastic to keep rats and insects from crawling through drains. These conditions created an ideal environment for the spread of communicable diseases.

In global health discussions, prisons are frequently forgotten spaces, hidden away from public view, making them easy to ignore. But diseases do not respect walls. Incarcerated individuals eventually return to society, staff go home to their families, and visitors come and go. The health of those inside directly affects the health of the wider population.

A practice I found particularly interesting was the designation of “health officers” within each block. These detainees tracked medications, encouraged hygiene, and acted as peer educators, supporting adherence to treatment and basic health practices. Although imperfect, it is a practical response to staffing shortages and a testament to resilience in harsh circumstances.

My experience underscored how improving prison healthcare directly benefits society. One detainee told me this was his first comprehensive health screening in years. Many shared his gratitude for being treated as individuals deserving care. The advanced technology used in our screenings allowed rapid detection and immediate initiation of treatment plans, significantly curbing potential disease outbreaks. However, technology alone does not solve systemic neglect. It requires political commitment, adequate funding, and a shift in societal attitudes. Reflecting upon my experience, the ethical imperative became clear: healthcare is not a privilege but a universal human right, irrespective of a person’s incarceration status. Observing first-hand how Health through Walls worked diligently to reinforce this right was inspiring.

The challenges remain. Prisons in Mozambique operate with limited resources, struggling with infrastructural degradation and insufficient medical staffing. These conditions do more than facilitate disease; they also perpetuate cycles of suffering and marginalization. Globally, prisons act as amplifiers for TB. WHO data shows that TB incidence in prisons can be more than ten times higher than in the general population; a statistic confirmed by our intervention. Overcrowding, poor ventilation, and lack of healthcare ensure that disease spreads beyond prison walls, endangering communities. To ignore prison health is to endanger public health.

The results of the blitz proved what is possible when resources, technology, and collaboration align. Still, sustaining these gains requires more than technology. It demands political will, stable funding, and a shift in perception. Incarcerated people must be seen as part of the community, entitled to equal standards of care. The Mandela Rules enshrine this principle, yet prison healthcare is too often neglected.

This work is never done alone. I am grateful to the team that led and taught me: Ivan Calder (CEO – Health through Walls); Dr. Anne Spaulding; Dr. Amadin Olotu; Dr. Marc Stern; Dr. Cremilde Anli; Mário Vicente; Rachel Boehm; Angel Gressel; Andy Leslie; Jane Reich; Betty Colburn; and to the SERNAP officers and health staff who made each day possible. I am grateful to my hosts and friends, Leonor and Naby Jamal, whose hospitality showed me the beauty of Mozambique beyond the prison walls.

For me, this experience was humbling. I left with a clear lesson: investing in prison healthcare pays dividends for public health. Health through Walls’ work in Mozambique shows what is possible and why it must continue. No wall, however high, can block the shared responsibility we have for one another’s health.

As global citizens, healthcare professionals, and policymakers, we must recognize that prison health reflects our values as societies. Improving conditions behind bars demonstrates a commitment to dignity, equity, and health for all. Prison walls may separate people, but they do not contain disease. If we want healthier, safer communities, we must start with the places we too often ignore.

The question is not whether we can afford to care for those behind bars. It is whether we can afford not to.

Gonçalo Ribeiro das Neves is a student at the University of Toronto, pursuing a double major in Political Science and Global Health. He has worked with Health Through Walls in Mozambique, supporting AI-powered tuberculosis screening in prisons, and working directly with the CEO, providing research and grant-writing support. He is currently the President of the University of Toronto Portuguese Student Association, leading efforts to provide scholarships and mentorship for Portuguese-Canadian students. His passions include health equity, governance, and community building.

About Health through Walls:

Health through Walls is a non-profit organization grounded in the belief that access to quality healthcare is a fundamental human right, even for people behind prison walls. Since its founding in 2001 by Dr. John P. May, Health through Walls has worked across the globe, including significant partnership delivery in Haiti, Dominican Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo, Jamaica, Malawi, Mozambique, the Central African Republic, and Romania, in bringing essential and progressive health services into correctional settings. The organization develops training programs for prison and local health staff, funds clinical missions to deliver care, and supplies medications and life-changing materials. It addresses urgent health issues such as infectious diseases and chronic illness, partnering with prisons, governments, NGOs and communities to build sustainable health systems. Health through Walls recognizes that the health of people in prison is deeply connected to public health overall, and its work extends beyond confinement, promoting continuity of care, dignity, and healthier societies.

To learn more about Health through Walls, become involved, or make a donation, visit the website: www.healththroughwalls.org and/or contact CEO Ivan Calder on +1 347 712 0271 or via [email protected].