Interview

Ángel Luis Ortiz González

Secretary General of Penitentiary Institutions, Spain

In recent years, significant investments have been made in modernising the Spanish prison system through a series of legal reforms, in line with the framework decisions of the European Union. In addition, the prison population and the incarceration rate have decreased. Even so, challenges are a constant for the agency led by Ángel Luis Ortiz since 2018.

In this interview he succinctly shares his achievements and the direction where he wants to take the institution.

What are the main achievements of the Spanish correctional system?

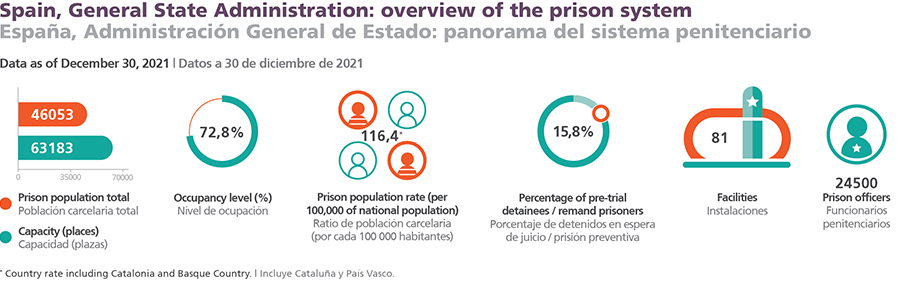

AO: The first is having provided the majority of penitentiary centres with adequate infrastructures. Thanks to investments made over the last 40 years, prison occupancy is currently at 72,8%, which means that overcrowding has disappeared.

During the period 1980-1983, a facility construction programme was drawn up, with a budget of 22,500 million pesetas (approximately 135 million euros), an amount to which another 4,400 million pesetas (more than 26 million euros) was added for the creation of two high-security centres and two hospital care centres.

In order to rationalise and centralise the construction of prisons, the State Society for Penitentiary Infrastructures and Equipment was established in 1992. Since then, it has overseen the building of twenty-six standard centres, thirteen probation offices and four mothers’ units, all in operation today.

In addition, since 1979 we have had a guaranteed legal framework that clearly defines the rights and obligations of persons deprived of liberty while establishing the Prison Surveillance Judge as the guarantor of those rights. This allows authentic judicial control over custodial sentences.

This control has made it easier for surveillance judges to rule over diverse matters including x-ray searches, force-feeding, the use of coercive means on inmates, cell searches, body searches and communication with the outside world.

To what extent are these achievements linked to factors such as technological change and alternative sentences? And what are the main challenges that the system is facing today (apart from the COVID-19 pandemic)?

AO: Although the General Penitentiary Organic Law approved in 1979 does not mention alternative measures, also called community penalties, the Penal Code introduced ‘community service’ and treatment programmes as a way to substitute income in prison. The volume of these alternative measures is currently greater than 100,000 sentences per year and, in practice, this means a relief in prison admissions.

The prison population is around 46,000 people in state-run centres, and approximately 20% are in third grade (semi-liberty).

Within that third grade, more than 5,000 inmates were under electronic monitoring during the most critical moments of the pandemic.

New technologies – both in the control of inmates outside prison and in their use as passive elements that contribute to security – are facilitating the improvement of the Spanish prison system.

By having adequate infrastructures and a guaranteeing legal framework, the challenge for the Spanish prison system is to provide all inmates with treatment according to their needs, an increasingly wide and specific offer.

To this end, in recent years we have developed new programmes such as the one designed for those convicted of hate crimes. Aware of the complexity of the problem, we concluded that it was necessary to intervene with people deprived of liberty for this type of crime and thus the Diversity Programme was born.

Among the causes addressed are discrimination based on sex, gender, religious belief, and xenophobia.

Economic crimes have also been the object of study and PIDECO focuses on them. We have also launched actions for short sentences for gender violence. It is all about optimising the passage through the penitentiary system.

The latest in the area of treatment relates to restorative justice programmes, in which the victim has an essential role, with work also being done to hold the offender accountable. These processes, which sometimes culminate in encounters between the two parties, give the victim the opportunity to be heard and help them find closure and sometimes even overcome complicated grief.

More than 5,000 inmates were under electronic monitoring during the most critical moments of the pandemic. New technologies – both in the control of inmates outside prison and in their use as passive elements that contribute to security – are facilitating the improvement of the Spanish prison system.

JT: Prison officers in Spain have requested, among other improvements in working conditions, the reclassification of penitentiaries, and to be recognised as agents of authority (Source: El Confidencial).

What is your vision and strategy for prison staff? And how important is the issue of prison officers’ training and development?

AO: The roadmap involves improving prison officers’ training, and given their unique skillset, recognising them as agents of authority. We are also working to improve the working conditions of these professionals, who play an important role in the treatment of people deprived of their liberty.

They are the ones who are in direct contact with the prison population, who accompany inmates while they are deprived of liberty. Training, both initial and continuous, is essential to ensure that prison staff carry out their duties correctly.

Spain has some renovated facilities, however it has lacked a training centre up to the same standards of quality as those facilities, until now.

That’s why this year we have decided to create the Penitentiary Studies Centre, based in Cuenca. Over the next few years, the necessary reforms will be made to put it into operation.

For now, work has already begun in that city in collaboration with the University of Castilla-La Mancha and classes are being taught in the city campus.

This initial training for those aiming to work in Penitentiary Institutions consists of two phases: a theoretical course at the Study Centre and a practical programme in prisons.

Furthermore, nearly 6,000 people are receiving continuous training each year in face-to-face, online and decentralised, in prison institutions.

JT: In addition to Catalonia, which already had autonomous management of its prisons, from October 2021 the Basque Country also assumed responsibility for its three prisons (Source: El País). Unlike other countries, the Spanish prison system is not divided into federal and regional authorities with different and complementary powers.

What is the form of governance and collaboration like among the different jurisdictions, that is, between the state penitentiary administration and the various regional administrations?

AO: In Spain there is no such difference. The Spanish constitutional framework allows certain regions to assume competence for the execution of sentences.

There is one overarching regulatory framework, but the execution of this framework can be carried out either by the General State Administration or by the regions. Two have assumed that competence – Catalonia and the Basque Country – the latter on October 1, 2021.

The relationship with these regions is one of complete collaboration: we act in a coordinated way through agreements and dialogue prevails.

Radicalisation is a challenge that, due to its global dimension, must be addressed by all prison systems. In Spain, a programme has been offered for years to deradicalise those convicted of terrorism. This issue is one of the Spanish Penitentiary Administration’s main objectives.

JT: The latest “SPACE I” report mentions that Spain has certain values significantly higher than the European average, namely, the long duration of prison sentences, the percentage of older inmates (50 and over), and the percentages of both women and foreigners among the prison population.

How are you addressing and managing these specific challenges?

AO: Although crime rates in Spain are among the lowest in Europe, incarceration rates and the average length of stays in prison are among the highest. Fortunately, since the crime rate is low, the number of people in prison is descending, to the point that in the last eleven years the number of inmates has decreased by 20,000. This decrease, together with more than 15,000 available places, means that occupancy in Spain is around 72,8%.

This situation makes it possible to manage life inside the prisons with a certain normality, even more so if one considers that eleven years ago there were 22,000 prison officers and today there are over 24,000. Furthermore, a recruitment drive over the last four years is adding 4,403 new workers to that figure, of which 1,100 will be incorporated in 2022.

JT: Another pressing concern is that of radicalisation and violent extremism within the prison population.

How are you facing this challenge, and what is the General Secretariat of Penitentiary Institutions doing to prevent and counter radicalisation within the system?

AO: Radicalisation is a challenge that, due to its global dimension, must be addressed by all prison systems. In Spain, a programme has been offered for years to deradicalise those convicted of terrorism. This issue is one of the Spanish Penitentiary Administration’s main objectives.

Regarding jihadist terrorism, a collaboration agreement has recently been finalised with the Turkish authorities that has allowed Spanish officials to train their Turkish counterparts in this matter for more than two years.

The strict measures that have been adopted to deal with the health crisis have included suspending exit permits and transfers between centres, more rigorous controls in occupational workshops and a limitation of communications in visiting booths.

In fact, visiting booths were suspended at the height of the pandemic and, since then, videoconferences have been promoted.

What has it been like to lead and manage the General Secretariat of Penitentiary Institutions during the pandemic? What challenges and opportunities has the public health crisis presented and will the changes remain after the pandemic?

AO: The management and the measures adopted have contained the advance of the pandemic within Spanish prisons.

The cumulative incidence per 100,000 inmates is 1.5 times lower than in the general population. As of December 30, 2021, within the sixth wave, we had 303 positives for COVID-19; most were asymptomatic and three were hospitalised. In addition, since the start of the pandemic, the mortality rate has been 8.2 times lower than in the general population: we have had eleven deaths; almost all were people with previous pathologies.

During this time, around 90,000 people have passed through Spanish prisons.

The strict measures that have been adopted to deal with the health crisis have included suspending exit permits and transfers between centres, more rigorous controls in occupational workshops and a limitation of communications in visiting booths. In fact, visiting booths were suspended at the height of the pandemic and, since then, videoconferences have been promoted.

Regarding sanitary measures, early diagnoses of symptomatic patients have been carried out; they were isolated and sent to unoccupied units.

The use of facemasks and physical distancing have been promoted and quarantines have been carried out after return from leave or after receiving visitors. In addition, at the end of the year, more than 85% of the inmates had completed the vaccination schedule. Less than 2% had refused the vaccine.

I do think it is important to highlight that, thanks to the informative and educational work of the prison staff, the inmates have understood that restrictions have been due to public health reasons. This has meant that during the entire pandemic there have been no serious incidents due to this cause.

Ángel Luis Ortiz

Secretary General of Penitentiary Institutions, Spain

Ángel Luis Ortiz has a Law degree from the Complutense University of Madrid. He has an extensive career in the courts, where he started as an assistant when he was only 18 years old. He was an officer and magistrate assigned to different courts, including Madrid Penitentiary Surveillance Court number 1. For ten years he was an advisor to the Justice and Prisons Area of the Office of the Ombudsman. In addition, he has been the coordinator of a monographic report on the “Situation of prisons in Spain”. He assumed the position of Secretary General of Penitentiary Institutions on June 18, 2018, after having served as director of Madrid City Council’s Legal Department for two and a half years.