Noteworthy Practice

Supervised Release Program

In recent years, communities across the United States have begun confronting a major social problem: Half a million (1) people are sitting in pretrial detention in local jails spread all around the country. Collectively, these individuals have been accused of committing a crime but have not been convicted. In other words, they are simply waiting for their day in court.

For many, the reason that they are incarcerated is that a judge has set bail – money that a defendant in a criminal case must pay as collateral to secure their freedom while their case is pending. In theory, bail incentivizes attending court and avoiding re-arrest. In practice, it means that only those among the accused who can afford bail can buy their freedom pretrial. Everyone else – all the people who lack sufficient resources – remain locked up.

This process is unfair and worsens racial inequities throughout the criminal justice system. It also leads to long-term harms: People held in jail pretrial are cut off from their families, their jobs, and community supports. Among other things, research (2) has shown that even a short period of pretrial detention increases a person’s likelihood of reoffending in the future.

Americans of all political beliefs have come to recognize the urgent need to make this system more effective, fair, and equitable. But what should replace it? How can the public’s interest in the efficient administration of justice be balanced with the need to give everyone an opportunity to remain free while their case is pending?

A growing number of cities and states across the U.S. are answering this challenge by changing their laws to move away from setting bail and instead considering the risk that a person will not show up for court or will be re-arrested, and then making a release decision based on that information.

New York City has become a national leader in recent years in reducing pretrial detention.

Historically, judges in the City have released most people charged with crimes without setting bail or imposing other conditions – a status known as release on your own recognizance, or “ROR.” The overwhelming majority of people who are ROR-ed successfully return for their court appearances.

Building on this success, New York City in 2009 began piloting a new program to allow people who would otherwise have had bail set or been detained pretrial to be released under specific supervisory conditions. Known as Supervised Release, the program requires people to report in the community for regular check-ins with case managers who provide support services and voluntary connections to resources that address barriers to attending court.

During this period, eligibility for Supervised Release was limited to people charged with lower-level crimes, known as misdemeanors, and only non-violent more serious felony offenses (3). After initial findings showed encouraging results in Queens (4), Manhattan (5), and Brooklyn (6) – including reductions in pretrial detention without an increased risk of people missing court appearances—the Supervised Release program was expanded to all five boroughs of New York City.

This citywide expansion happened as local efforts to reduce pretrial detention took on mounting urgency and as Supervised Release became an essential pillar in the government’s plan to close Rikers Island, New York City’s notoriously unsafe jail complex.

Then in 2020, a sweeping new reform law took effect in New York State designed to significantly reduce pretrial detention across the entire state by dramatically restricting the use of bail except in certain cases (the main exceptions being for serious violent charges). Where a judge does find a risk that the individual might not appear for court, the law requires that the court impose the “least restrictive” condition necessary to ensure court attendance, such as court date reminders or pretrial supervision.

Unlike some other jurisdictions, New York State prohibits considering “dangerousness” or likelihood of re-arrest in deciding pretrial release; this decision was based in part on concern that such a standard would reinforce historic racial inequities on who is granted pretrial release.

As the state legislative reforms took effect in 2020, New York City eliminated all eligibility restrictions for Supervised Release. This led to a dramatic expansion of the program, which is centrally funded by the City and currently operated by four different nonprofit providers (7). In 2021, the Supervised Release program served over 12,000 people citywide, up from a few hundred participants per year when the pilot program first began a decade earlier.

In practice, a judge will order Supervised Release if they believe an individual poses a risk of flight from their jurisdiction; every judge has at their disposal the results of a “Failure to Appear” assessment (8) – a validated tool that measures a person’s likelihood of appearing in court.

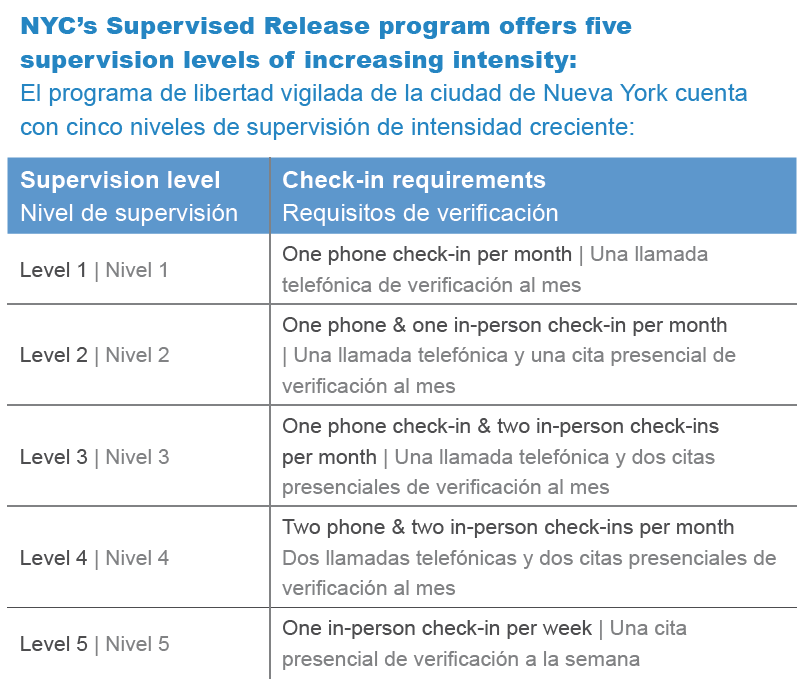

This assessment is combined with the seriousness of the charge (which determines whether under the law, bail could be set or pretrial detention ordered) to assign an individual to one of five possible supervision levels.

Upon enrollment in Supervised Release, supervision begins immediately, and participants are assigned to a case manager.The program’s use of social workers and case managers from local nonprofit agencies to provide supervision distinguishes New York City from other jurisdictions that utilize law enforcement officers in this role. Supervised Release case managers are trained to recognize needs and connect participants to voluntary services in their communities that can address those needs.

And the Supervised Release providers are themselves couched within extensive networks of partner providers specializing in assistance with housing, mental health, substance use, and employment needs; these robust networks enable program staff to provide individualized responses to each program participant over the course of their case.

At check-ins, case managers remind program participants of upcoming court dates, provide encouragement to follow court orders, and discuss any barriers for attending court and program check-ins. If needed, participants will receive resources to pay for transportation and a phone to ensure stable communication. For many, these regular touch points are critical.

Another key program element is regular communication between program staff and the court. Using a standard compliance form, staff inform the judge, prosecutor, and defense attorney prior to each court date whether the participant has been attending all check-ins and complying with other program requirements. Non-compliance, as well as any re-arrests, are reported to the court; the judge then decides on the appropriate response. The program also employs a “graduated response” policy whereby supervision requirements can be increased or decreased to incentivize a participant’s compliance and reward their progress.

More than 35,000 participants were enrolled in the Supervised Release program in New York City from 2016 through 2021 – and this volume continues to grow. In Brooklyn alone, enrollment has increased nearly 300% in the past 5 years. Each of these program enrollments represents a person who might have otherwise been incarcerated pretrial.

New York’s recent legal reforms have also brought a shift toward more serious charges. In 2020, nearly one-quarter of all new Supervised Release participants were charged with a violent felony offense (9) – up from 3% in previous years when most of these cases were ineligible for enrollment. The increasing severity of charges, coupled with increasing program volume, strongly suggests the court system’s confidence in Supervised Release as a pretrial release option. Moreover, Supervised Release is serving, in practice, as a true alternative to pretrial detention.

This is likely because Supervised Release is succeeding at getting people to show up for their court appearances. Among other promising findings:

- 87% of participants discharged since 2016, never missed a single court date (10) while enrolled;

- A recent independent evaluation (11) found that Supervised Release reduced both bail and resulting pretrial detention, while having no effect on the rates of failure to appear in court or re-arrest;

- 87% of participants were not arrested (12) on a new serious (felony) charge while enrolled in Supervised Release from 2016 through 2020.(Controlling for time, another analysis (13) found that in any given month, only around 1% of Supervised Release participants were re-arrested for a violent felony, and on average, 93% were not re-arrested at all);

- Compliance data from 2020 and 2021 show that program participants attended around 98% of their required check-ins (14).

These results are key, especially given existing research (15) documenting that the alternative—pretrial detention—increases recidivism rates in the long term.

The COVID-19 pandemic brought widespread disruptions to the court system. Supervised Release adapted quickly, implementing practices such as remote check-ins with case managers and providing phones if needed. Even during this period, the program successfully maintained regular connections with program participants. As courts have moved back to more regular in-person operations, Supervised Release is emerging as a tested program that has effectively gone to scale.

The challenges ahead for Supervised Release providers and the program’s stakeholders are to further strengthen the program’s services and address any gaps. For example, there is increasing general concern about crime in New York City.

Supervised Release providers have been collectively working to identify how the program can respond to public safety concerns without disturbing the model’s purpose and integrity. These responses include efforts to provide enhanced voluntary support in response to more serious charges involving the use of a firearm, and more rapid reengagement of a participant when they are re-arrested.

Other initiatives include providing additional program spaces in underserved neighborhoods and expanding partnerships with community-based service providers to best serve the wide spectrum of individuals who have criminal cases in New York City’s courts.

As it grows, Supervised Release will keep providing opportunities to thousands of people each day to remain living with their families, working at their jobs, and tapping into support in their communities while they await the resolution of their criminal case.

More than ten years after its inception, Supervised Release has become a model for an effective way to reduce pretrial detention that aligns with public safety goals and helps ensure people come to court while, at the same time, giving everyone accused of a crime a fair chance to stay out of jail.

References

(1) Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice (2021). Jail Inmates in 2020 – Statistical Tables.

(2) Lowenkamp, C.; VanNostrand, M, & Holsinger, A, (2013). The Hidden Costs of Pretrial Detention.

(3) In 2018, the SR program launched a pilot for young adults charged with violent felony offenses or designated as high risk for felony re-arrest; high court attendance rates in this pilot laid the groundwork for expanding the program to a more charge-diverse population.

(4) Solomon, F. (2013). CJA’s Queens County Supervised Release Program: Impact on Court Processing and Outcomes.

(5) Solomon, F. (2018). Brief No. 42: Reducing Unnecessary Pretrial Detention: CJA’s Manhattan Supervised Release Program.

(6) Hahn, J. (2016). An Experiment in Bail Reform: Examining the Impact of the Brooklyn Supervised Release Program.

(7) The Center for Court Innovation currently runs Supervised Release in Brooklyn and Staten Island; The Fortune Society in the Bronx; the NYC Criminal Justice Agency in Queens; and the Center for Alternative Sentencing and Employment Services (CASES) in Manhattan.

(8) https://www.nycja.org/release-assessment

(9) Supervised Release Program Results, Five Years In (2021).

(10) NYC Criminal Justice (2020). Supervised Release Annual Scorecard 2020.

(11) Process and Impact Evaluation of New York City’s Pretrial Supervised Release Program.

(12) NYC Criminal Justice (2020). Supervised Release Annual Scorecard 2020.

(13) Supervised Release Program Results, Five Years In (2021).

(14) NYC Criminal Justice (2021). How many people with open criminal cases are re-arrested?

(15) Process and Impact Evaluation of New York City’s Pretrial Supervised Release Program.

David Hafetz

David Hafetz is the Deputy Director for Supervised Release, the Center for Court Innovation. At the Center, David helps lead the Supervised Release Program, and also served as the founding director of an initiative launched in Manhattan in 2020 to provide a continuum of community-based alternative to incarceration options for people charged with all levels of criminal offenses. Previously, David served as Executive Director of Crime Lab New York, a University of Chicago research center. David holds a B.A. from Princeton University, and a J.D. from Columbia University.

Tia Pooler

Tia Pooler is the Deputy Director of Data Analytics and Applied Research, the Center for Court Innovation. Tia conducts and oversees data management, data analysis, reporting and research at the Center’s operating projects and initiatives, including Supervised Release. Recent research projects include a mixed-methods evaluation of Brooklyn’s Young Adult Court, and an evaluation of the Harlem Parole Reentry Court, among others. She holds a B.A. in Economics from Boston University, an MSc in Criminal Justice Policy, and an MSc in Social Research Methods, both from the London School of Economics.