Interview

Rafael Velasco Brandani

National Secretary for Penal Policies, Ministry of Justice and Public Security, Brazil

In this interview, Rafael Velasco Brandani, heading the National Secretariat for Penal Policies (SENAPPEN), shares the challenges of Brazil’s penitentiary landscape, and the progress made in the fight against organised crime and the reintegration of inmates.

SENAPPEN is a body linked to Brazil’s Ministry of Justice and Public Security, created in January 2023 through the transformation of the former National Penitentiary Department (DEPEN). With its new structure, including a new Directorate focused on Citizenship and Penal Alternatives, SENAPPEN has a number of duties, such as providing technical and financial support to the Federative Units, collaborating in the construction and renovation of prison units, and overseeing penal establishments and policies.

What are the primary challenges facing the Brazilian prison system in its battle against organised crime?

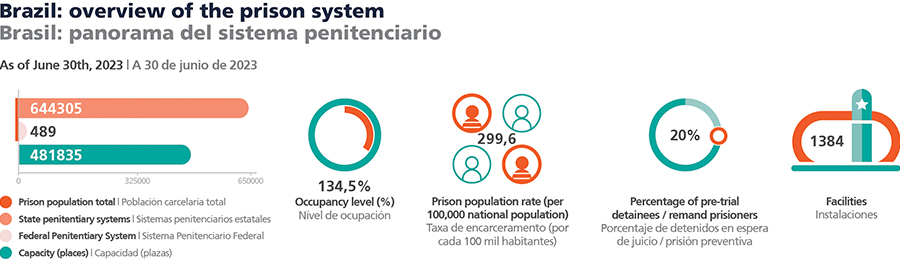

RVB: The challenges facing the Brazilian prison system in relation to organised crime are multifaceted and intricate. Firstly, it is imperative to acknowledge the persistent issue of overcrowding in Brazil’s prisons. This problem has played a pivotal role in the emergence and empowerment of criminal factions like Primeiro Comando da Capital and Comando Vermelho, entities that wield significant influence both within and beyond prison walls.

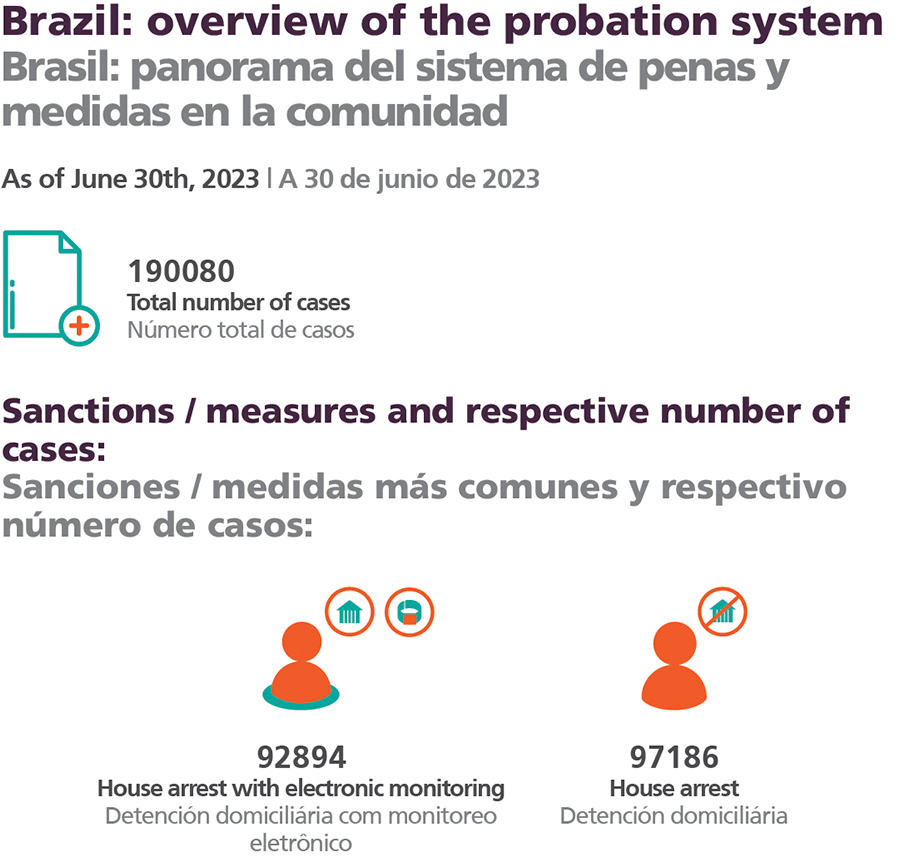

A comprehensive reform of the prison system is indispensable to address non-violent offences effectively, offering alternatives like electronic monitoring. The underutilisation of these alternatives further contributes to the expansion of factions within prisons through the recruitment of people whose incarceration could have been avoided.

A notable issue is the arrest and classification of many drug users as drug dealers, leading to their incarceration alongside regional drug dealers affiliated with specific criminal factions. Consequently, individuals who entered the system as users often emerge from their sentences as drug dealers and full-fledged members of a criminal faction.

Brazil is a country with high drug consumption and serves as a crucial distribution channel for other countries in the European bloc, North America and other regions of the world. This inadvertently bolsters the economic strength of these gangs, making them one of the biggest challenges in the country. Various actors in the system, including prison officers, staff members, suppliers and other workers in contact with the prison units, come under a lot of pressure from factions. Many succumb to bribery or coercion, aligning themselves with criminal factions and facilitating their activities.

The lack of investment in infrastructure, security, training and social reintegration programmes in prisons is another factor that strengthens criminal factions. In some states, the absence of adequate resources allows factions to fill this gap and gain economic influence over prisoners.

Could you tell us about the need for a Federal Penitentiary System focused on taking in high-risk individuals and organised crime leaders?

RVB: Around 2002, due to the absence of suitable facilities for housing extremely dangerous prisoners, it became common practice to transfer them between states based on availability and agreements between state secretaries. This constant movement of prisoners fostered a network of connections, exposing them to new inmates and criminal factions, consequently escalating opportunities for crime expansion.

In 2004, a series of attacks on the Brazilian state occurred as a result of this prisoner migration, prompting us to realize that this approach was inadequate. Consequently, the need arose to establish a federal prison system.

The system’s first two prison units were inaugurated in 2006, in Catanduvas and Campo Grande. These facilities were purposefully designed to effectively accommodate high-risk prisoners, and it was during this time that the role of federal prison officers, later referred to as federal penal police officers, was established. These professionals underwent specialized training to manage this particular demographic, and the units were structured to adapt to this unique reality.

The creation of the federal penitentiary system has proven to be a potent and efficient tool in combating organised crime. It allows us, in a way, to dismantle the leadership of criminal factions, severing their ties with these organisations.

In doing so, we prevent the influence of these leaders and their entourage, including their legal representatives, from exerting undue influence on prison units that typically had no contact with certain factions.

The Federal Penitentiary System is well-prepared to accommodate this specific public and administer appropriate response within a secure environment.

Only those directly involved with this system can truly grasp the immense challenge of managing a group of inmates whose hypothetical collective economic capacity would rival that of some countries. It is a monumental task. Nonetheless, we have dedicated officers leading this mission, and we are committed to continuing to reap the positive results that this system has already yielded to date.

What other challenges are among SENAPPEN’s national priorities? And how does SENAPPEN support the prison administrations of the federal units?

RVB: In some regions, there is a notable absence of investment in programmes aimed at improving the education and vocational skills of inmates. This deficiency hinders their rehabilitation and reintegration into society. In several federal units, a significant portion of inmates lacks proper civil identification, a critical requirement for enrolling them in social programs and services. We work with organisations such as the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the National Council of Justice to promote the acquisition of civil identification for prisoners. This is pivotal for the effective implementation and management of social initiatives.

It is essential to reform the prison system to provide non-violent or minor offenders with viable alternatives to incarceration. And this needs to go beyond placing them under of electronic monitoring, extending our efforts to collecting data on inmates’ families and their housing conditions to facilitate their rehabilitation and prevent them from reoffending. This strategic approach aims to break the cycle of recidivism, which most of the time occurs for financial reasons because they haven’t found a job.

Social offices play a pivotal role in monitoring and reintegrating prisoners into society, providing support from social workers and pedagogues for education and professionalisation. This support is critical to ensuring inmates’ employability and preventing them from experiencing difficulties that could lead them to commit crimes or join criminal gangs.

With these appropriate and surgical investments, it is possible to reduce state spending on public security, by breaking the cycle of criminal recidivism. Even in economic terms, it's simply five times cheaper to invest in a convict than to wait for that person to become a repeat offender.

Investing in the development of public management policies, such as the Penitentiary Fund, and services for prisoners is crucial. This includes professionals like social workers, psychologists, nurses, and lawyers who generate reports to support the decisions of magistrates, the Public Prosecutor’s Office, and the defence. This approach aims to accurately assess prisoners, preventing situations like the current one, where over 30,000 individuals are incarcerated for non-violent theft offences.

We are in the final stages of a collaborative project involving all states, which is the National System of Penal Alternatives. This effort originated in the National Council of Justice (CNJ) and we are now completing it. The aim of this system is to share responsibilities and properly monitor the implementation of penal alternatives throughout the country.

Substantial investments in employment and education are fundamental for empowering individuals and breaking their ties with criminal factions. We have established over 400 concrete factories within Brazil’s prisons, with the goal of producing nearly half a million units daily, beginning with hexagonal blocks for street paving.

In the upcoming year, we also plan to foster the creation of social cooperatives. These public workshops will provide trained graduates in fields like metalworking or carpentry with the opportunity to start their professional careers upon release from the prison system, through the use of vouchers. This support aids in their reintegration into society and the job market, ultimately enabling them to establish their businesses over time.

Lastly, we have made substantial investments in evaluation and monitoring. We are taking a comprehensive approach to gather data from all 1408 prison units in Brazil, receiving weekly information on various aspects, including participation in educational programs, employment, and support services. This allows us to maintain a clear overview of activities in all units and make informed decisions.

JT: The introduction of body cameras for Penal Police has been a subject of discussion with various states across the country.

Could you please elaborate on the significance of this initiative, and the progress achieved thus far?

RVB: I’ve met with representatives from both federal and state unions, and we had open and constructive dialogues about implementing body cameras. While it’s true that some professionals and union representatives raised specific concerns, the majority recognise the necessity and importance of this undertaking.

When we consider public security, we should note that the prison system is different from other areas of police activity. Actions inside prisons are already recorded by cameras installed in the facilities. What body cameras bring to the table is an additional perspective. While existing cameras record police actions in common areas, body cameras offer a clear, firsthand account of events, reducing ambiguity in the face of differing claims.

In the short term, I believe the deployment of body cameras can play a pivotal role in curtailing unfounded accusations because individuals involved will be aware that their interactions are being meticulously documented. This, in turn, fosters a safer and more transparent environment.

However, it’s essential to understand that the effectiveness of body cameras is not based solely on the presence of the equipment itself. The protocol for using and managing the images is just as important. We need an active monitoring and inspection system, at least initially by sampling, to ensure that the equipment is being used correctly. In addition, we are considering the implementation of artificial intelligence systems that can help identify suspicious behaviour in the images, alleviating the workload of monitoring operators. Finally, it’s important to discuss specific issues related to prisoners’ privacy within their cells and the storage of images in the cloud, which has significant costs.

What’s crucial to emphasize is that there is no significant resistance on the part of the states regarding this initiative; on the contrary, there is a great deal of positive expectation surrounding it. This measure is expected to demonstrate that procedures are being carried out correctly, fostering increased accountability and trust within the prison system.

Rafael Velasco Brandani

National Secretary for Penal Policies, Ministry of Justice and Public Security, Brazil

Rafael Velasco Brandani has been a career penal police officer, specialising in Criminal Law, Public Administration and Penitentiary Management. He is committed to the cause of resocialization and the defence of human rights. He worked as a civil servant in the penitentiary administration at the Minas Gerais Social Defense Secretariat, from 2010 to 2015. Prior to assuming his current role, he was Undersecretary of the Maranhão Penitentiary Security Administration, where played a crucial part in revolutionising the Maranhão prison system.