Interview

Nivaldo Restivo

Colonel, Secretary of State for Penitentiary Administration , São Paulo, Brazil

How big is the overcrowding issue in the State of São Paulo prison system, and what measures are being taken to address it?

NR: Brazil has the third-largest prison population in the world, after the United States and China.

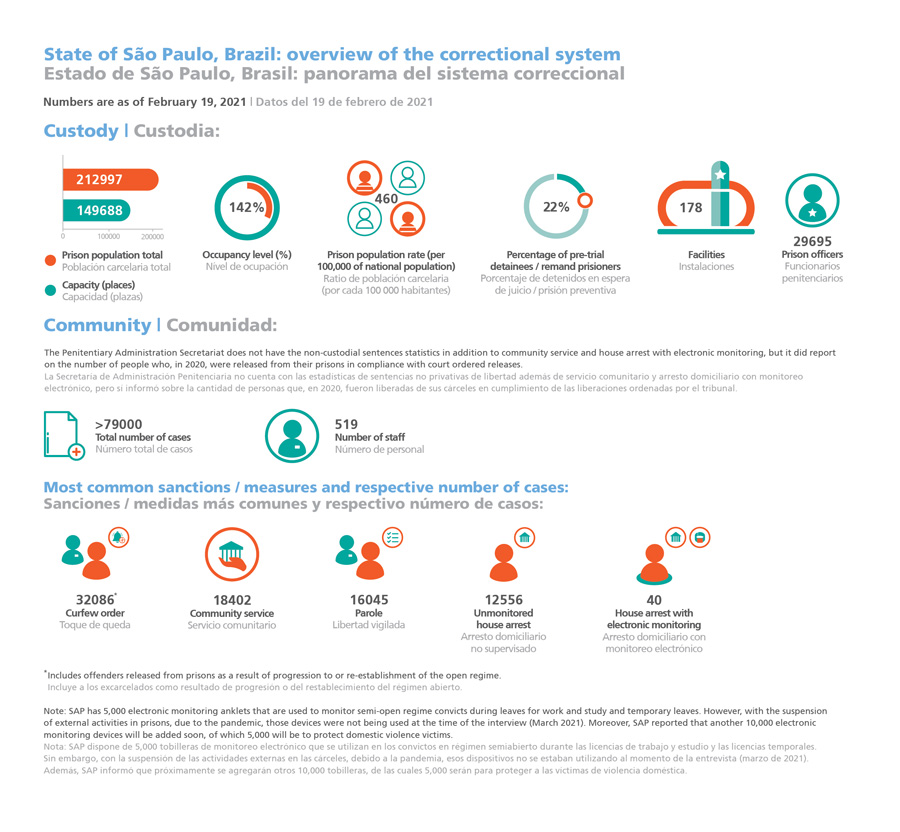

We have approximately 700,000 prisoners, and about a third of them are in the State of São Paulo, where currently we have around 213,000 people incarcerated for approximately 150,000 beds.

Thus, we have an overcrowding rate of around 42%, despite the efforts of the last decade, in which the Penitentiary Administration Secretariat (SAP, by its acronym in Portuguese) announced and completed thirty-three prisons with more than 30,000 spaces. In addition, in two years under my administration, we have already completed seven prisons, and we have another six under construction, which will add a total of 10,000 more beds.

However, adding infrastructure is not the only option for solving overcrowding. We should enact public policies that prevent people from being incarcerated and, if people are incarcerated, we need to work to make sure that they do not return to prison after having been released.

We achieve this by working on social reintegration. Here, in São Paulo, we have about forty thousand prisoners who work and approximately twenty-six thousand who study.

To what extent does São Paulo State non-custodial sanctions and measures system relieve the pressure on the prisons?

NR: In São Paulo, we have 86 Alternative Penalties and Measures Centres. The Judiciary Branch can sentence an offender to community service, among other penalties and measures, without resorting to deprivation of liberty. We have almost twenty thousand people serving non-custodial sentences, so our prison population would be much larger if we didn’t have these centres.

Above all, it is important that the person does not become a regular in the correctional system; that’s why we want to offer these offenders conditions to work, study or improve professionally. Since the beginning of the programme, more than 205,000 offenders have served community sentences. Our Secretariat oversees the completion of alternative sentences through our Department for Social Reintegration and Citizenship.

Community sanctions and measures can only be handed down to those offenders who have been sentenced to less than four years in prison term and if their crime has not been committed through violence or threats.

This Department is also responsible for rehabilitating and reintegrating prison inmates, so that they return to society as law-abiding citizens, without re-offending. São Paulo is the only Brazilian State that has an entire coordinating body exclusively dedicated to this purpose.

We will demand much better service provision from the private sector than the State can ofer today, including medical care, food, jobs and education for prisoners.”

JT: We are aware that São Paulo plans to award concessions for managing certain prisons to the private sector.

What is the current status of this process? And to what extent can partnership with the private sector help to overcome the overcrowding problem?

NR: We have two ways of establishing a partnership with the private sector. One of them involves the State building the prison and handing it over to private management – except for some specific functions, such as perimeter security and inmates’ transportation. At the moment, we have two new finished prisons, and we will launch the call for tenders to see which company will manage these units.

The other way is through a public-private partnership (PPP). Under this type of contract, the private partner will build the infrastructure and then operate it. This model is more beneficial because construction tends to be faster than when the State does it; moreover, the State does not invest in construction, and after thirty years – which is what our legislation provides – the prison is transferred to the State.

With both models, we will demand much better service provision from the private sector than the State can offer today, including medical care, food, jobs and education for prisoners.

We understand that meeting these requirements will increase rehabilitation and facilitate inmates’ social reintegration. The private sector can be vital in prison management because it has a solid legacy in terms of recidivism reduction.”

Those prisoners whose profile is more favourable to social reintegration will be held in the prison units under private concession.

In 2019 I visited American prisons twice, and I also went to London to learn about privatised prisons. Considering the possibility of public-private partnerships, and before developing and establishing our model for it, we tried to understand what works best worldwide. We concluded that it works very well in the United States and England, so we hope to succeed as well.

We are going to move forward with the two private prison management models. The one under which the prison is built by the State is already at an advanced stage; the call for tenders was launched in March 2021, and the plan is that in August 2021, it will already be in operation. Moreover, we have already structured the other PPP format and our expectation is that it will be implemented in the second half of 2022.

JT: Shortly after taking office as State Secretary, you have facilitated the transfer of First Capital Command – PCC leaders to federal prison units. Among those transfers is the alleged ringleader of this criminal gang himself.

How big is the problem of criminal gangs in the São Paulo prison system? How does your administration try to limit the power of these criminal gangs, and to what extent is it a concerted effort involving the federal administration?

NR: The prison system is divided by prisoner profile, so we have some units that harbour prisoners linked to organised crime. We do not have these types of prisoners spread throughout the system, so they do not co-opt other prisoners.

The São Paulo State Government is in charge of the São Paulo prison system. Any inmate in the São Paulo prison system must be subject to the State’s rules and administration. A prisoner may have power over another prisoner, but he will never have power over the State or negotiate with us.

We do not negotiate with inmates, and this is clearly shown by the fact that whoever declares himself to be the leader of a criminal organisation is sent to the federal prison system, where he will be in solitary confinement.

In addition, we have a very active intelligence system that enables early action in the units that house the inmates connected to criminal factions.

Intelligence detects an intention, and before it comes to fruition, we take action and transfer those involved. Even when we cannot anticipate the event, we know why it is happening and we have the appropriate solution.

This intelligence system is mainly based on human factor; much of the sensitive information we have access to is brought in by the inmates themselves. And we also use technologies in partnership with the São Paulo Public Security State Secretariat and the State Public Prosecutor’s Office.

We also have another alternative: a prison with a Differentiated Disciplinary Regime where we place prisoners who commit serious offences such as threatening an officer, demonstrating an escape plan or undermining the system’s security. Internment under this regime can last up to 360 days, and it is effected upon the authorisation of the judge.

This regime prescribes isolation from the mainstream prison population and grants only two hours of sunbathing per day without contact with any other inmate. If the criminal leadership is still very resilient, we request the transferring to the Federal Prison System, where we currently have sixty prisoners from São Paulo. Brazilian law allows the renewal of placement in Federal prison for up to three years to segregate those inmates who are highly harmful to the prison system of origin.

We have a very active intelligence system that enables early action in the units that house the inmates connected to criminal factions. Intelligence detects an intention, and before it comes to fruition, we take action and transfer those involved.”

Your management of the SAP has been committed to increasing the use web-based communication technologies, videoconferencing in particular. What does this investment in communication technologies involve, what are your objectives? And what are the results to date?

NR: Both remand and convicted prisoners who are answering for other crimes need to appear before the judge to participate in and keep track of their cases. Typically, these face-to-face court appearances have been conducted with police escorts. But we can accomplish them via videoconferencing.

When my team and I arrived at the SAP, there were thirty-nine teleconferencing devices in the prison system. The pandemic has favoured a technological expansion at that level because we did not want the judicial system to grind to a halt.

From a handful of devices and an old and expensive contract [each device costed R$11,300 per month (about €1,685 / $2,020)] we moved, in April 2020, to another much cheaper tool. Now all prisons have teleconferencing. We have 582 devices, and each one costs R$566 per month (€84 / $101). We have already saved R$3.5 million on the contract alone (more than €521,300 / $625,300).

In 2019, the cost of escorting prisoners to the courthouse had been around R$16 million (€2,382,580 / $2,857,433), but using teleconferencing we spent R$4.3 million (approximately €640,000 / $766,000) in 2020, i.e. we saved almost R$12 million (almost €1,783,000 / $2,137,000). And this not only reduces costs but also reduces risk because a prisoner moving around in the street presents the risk of escape or a car accident, among other things.

Our teleconferencing contract provides for 685 devices, all installed by the end of the first quarter of 2021. This technology has also resulted in a significant decrease in the number of people moving around inside the prison facilities. Now many lawyers and bailiffs use videoconferencing with prisoners. There are many advantages. This technology is something irreversible, it is here to stay, and we will expand it more and more.

Now many lawyers and bailiffs use videoconferencing with prisoners. This technology is something irreversible, it is here to stay (…)

What were the main challenges that the COVID-19 pandemic brought to the SAP? And to what extent have alternative measures to incarceration been implemented, amid the restrictions resulting from the pandemic?

NR: When the pandemic arrived in Brazil on February 26th, 2020, we already had a protocol applied in the São Paulo prison system. Our understanding was that we needed to avoid contact between inmates and people outside, so, first of all we suspended visits; families could no longer enter the prison to visit.

Moreover, we had prisoners who were allowed to leave, either to work or study, and could no longer leave the prison premises. Teachers and religious assistants were also unable to enter prisons. There was a total cutback to avoid contact that could spread the disease, and it worked very well. Still, it was and is challenging because prison officers enter and leave the prison daily.

At the same time, we invested a lot in cleaning, sanitisation and personal protective equipment; we have already distributed more than 3.7 million masks within the prison system.

These measures have been essential. Although we regret every death, of course, last year we had 213,000 prisoners, and out of 14,600 infected with COVID, 37 died, which is a case fatality rate of less than 0.3%. It should be noted that the case fatality rate is 2.9% in the State of São Paulo and 2.4% in Brazil as a whole. More staff died than prisoners: out of our 35,000 prison workers, 2,700 were infected with COVID, of which 42 lost their lives, which equals a case fatality rate of 1.5%.

Prisoners are well protected, and we have already tested almost 70% of the prison population. In addition, we conduct ongoing monitoring, isolating prisoners with symptoms that may prove to be COVID-19; we keep track, and if necessary, we perform the test. All of this has been done since the beginning of the pandemic.

During the limitations that we put in place because of the pandemic, prisoners could continue to communicate with their loved ones by letter.

Additionally, we set up the “Family Connection” programme because we understand the importance of the prisoner having contact with their loved ones. During the first phase of this programme, we allowed family members to communicate with prisoners by email, which prison staff printed out and delivered to the prisoner, who wrote out a reply on the back. The employee then scanned the reply and returned it to the family member. More than four million messages were exchanged.

We then progressed to the programme’s second phase, allowing prisoners to have virtual visits on weekends using our teleconferencing devices. And in November 2020, we began the gradual resumption of face-to-face visits, although these were limited to only two hours a day, with alternate days and according to the prisoner’s registration number. The Health Agencies approved this arrangement.

We are currently continuing with this system. However, the pandemic has returned to worrying levels, so when there are prison units with cases of COVID-19, face-to-face visits are suspended at those units. In these situations, the reestablishment of visits depends on the pandemic’s evolution over fourteen days. As soon as the pandemic is under control in these units, they will receive physical visits again.

There was a Supreme Court decision to release prisoners from the risk group in Brazil, which is why our prison population has decreased. With this judicial measure alone, we have released more than seven thousand inmates to unmonitored house arrest.

Nivaldo Restivo

Colonel, Secretary of State for the Penitentiary Administration, São Paulo, Brazil

Nivaldo Restivo has the rank of Colonel, graduated from the Barro Branco Military Police Academy and holds a master’s degree and Doctorate in Police Sciences for Security and Public Order from the Military Police Centre for Advanced Studies in Security. He was chief of staff to the former Secretary of Public Security. In addition to being Commander-in-Chief of the Military Police (2017-2018), he was Commander of the 1st Shock Police Battalion (ROTA) and the Special Operations Command of the Military Police (COE). He has held the position of Secretary of State since the beginning of 2019.