Interview

Katja Meier

State Minister of Justice and for Democracy, Europe, and Gender Equality, Saxony, Germany

In this interview we delve into the challenges facing Saxony’s Justice, with a particular focus on combating right-wing extremism. It also explores various aspects of the justice system, including rehabilitation, re-entry, probation, and dealing with juvenile offenders. Moreover, it highlights the crucial need to support families and children of prisoners.

JT: The Ministry you lead encompasses a multitude of responsibilities, extending beyond the field of Justice.

How do you effectively manage such a diverse range of portfolios? Could you outline your primary areas of focus?

KM: It is, indeed, a diverse range – but I frequently observe that there is something very productive about the thematic overlap and the intersections between all these different fields.

We have established a sort of ‘division of labour’ that works very well for us, with two State Secretaries, which is a bit unusual.

One of them focuses mainly on projects relating to democracy and equality, while the other one is in charge of justice and European affairs. This allows us to honour our primary responsibility: to maintain a strong and vivid democratic society and the rule of law.

They are integral to our major projects and policies, like the new Equality Act and the first major Transparency Act of the Free State of Saxony, both of which we have introduced in this election period. I am happy to see them come to fruition now, at last, having fought for them and negotiated hard for the past three years.

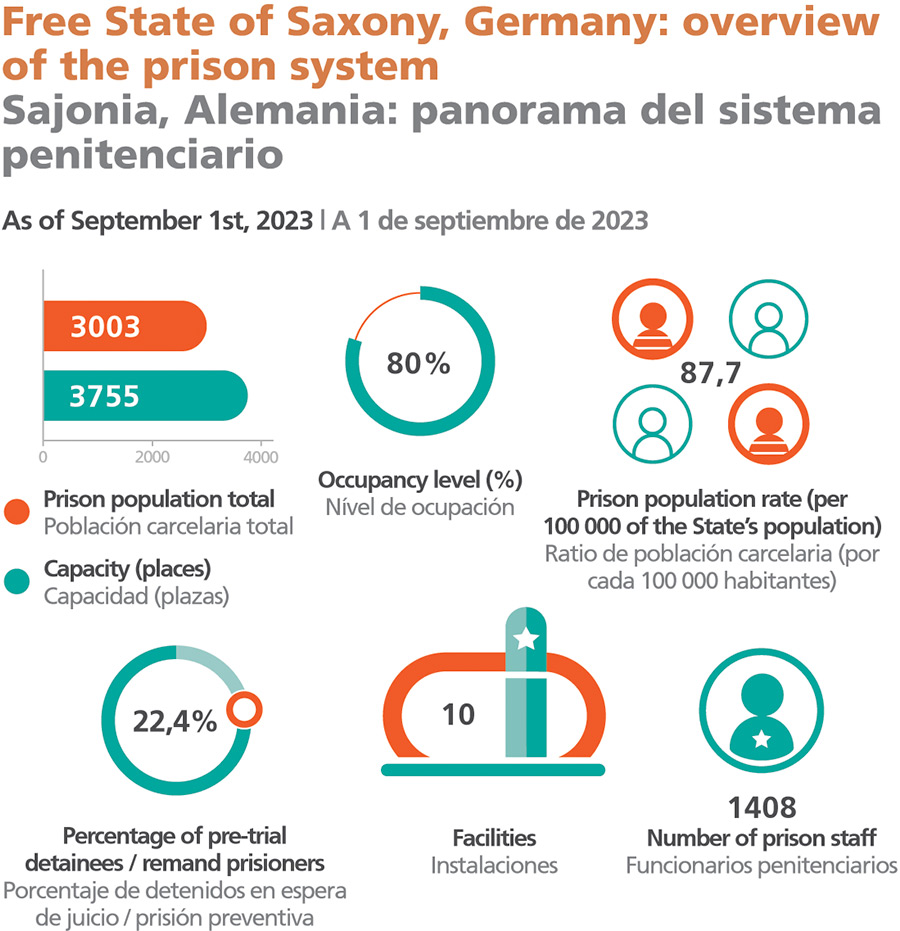

In the Free State of Saxony, the Ministry of Justice, Democracy, European Affairs and Gender Equality is in charge of all matters relating to the correctional system. Within the Ministry, Department IV (Penitentiary System, Social Services, Accommodation and Construction Matters of the Judiciary) runs five separate divisions, all of which deal with penitentiary matters, including security issues, prisoner education, petitions, and medical issues.

The ministry supervises ten authorities in charge of pre-trial detention, juvenile delinquents, and preventive custody, among other things. The Saxonian Penitentiary Law pursues two major objectives: to enable prisoners to eventually return to the social fabric without becoming reoffenders, and to protect the general population against crime.

The penitentiary is organised in such a way as to ensure we meet these goals. Like every other German state, the Free State of Saxony relies both on closed and open enforcement.

Moreover, we are developing a new regime – ‘Vollzug in freien Formen’ – where prisoners live in other facilities outside of the prison.

Within the realm of Justice, what are the most pressing challenges?

KM: The most pressing issue is how to deal with prisoners who are suffering from mental-health issues. About 70 to 80% of the prisoners could be diagnosed according to ICD-10 codes, with many issues linked to illegal drug consumption or alcohol abuse. Serious issues like psychoses are on the rise, which makes it far more challenging for correctional officers to guarantee everyone’s safety and to prevent prisoners from harming themselves or others. We are always looking for ways to improve the quality of psychiatric care in our ‘Justizvollzugskrankenhaus’ (a hospital exclusively for prisoners) in Leipzig. This hospital contains an extended psychiatric unit for up to 50 patients, and we are keen to hire additional doctors. To improve psychiatric care for the prisoners, it is crucial for us to compare notes with the other states in Germany and to make sure our doctors are on regional boards, because we need regular professional exchange. In May 2024, Saxony will be hosting a big, nation-wide conference on the role of psychiatry in prisons.

It is currently vitally important for us to attract new personnel. Not only do we need to fill vacancies when people go into retirement, we also have to be quick when it comes to filling vacant positions when people leave for different reasons. A few years ago, we launched a big campaign, “Job mit J”, involving radio and online advertising, and increased visibility at major career fairs. This campaign is a reaction to declining numbers of applicants, particularly where the prison workforce is concerned. We have set up a recruitment office for Saxony’s correctional system, which will start work on 1 January 2024.

JT: Saxony introduced a pioneering program to support the well-being of inmates’ families, especially their children, setting an example within the federal context.

Could you elaborate on the strategies employed to assist these families and children, and what concrete impacts and outcomes have resulted from this approach?

KM: Between 2010 and 2012, the COPING study was conducted in four European countries, including Germany. The results clearly indicate what a toll the situation takes on the families of inmates. This made it a priority for us in Saxony to make sure that these families would find help and support within the penitentiary system. In 2013, a working group came together, consisting of staff members from all ten correctional facilities in Saxony. This group provides advice and recommendations on how to make the situation bearable for the families, so that mothers and fathers can still take care of their children while they are imprisoned. We know that the children go through a lot in this situation, and we try to support them as much as possible.

The main benefit of having such a working group is that we never lose sight of how important the issue is. Sometimes there is a risk of focusing on one outstanding project, but once it is over, it simply disappears forever. We, on the other hand, are interested in developing long-term structures, and we are proud that other states in Germany have taken note of the example we are setting with our various initiatives.

We are mainly focusing on three pillars: ensuring that children and their imprisoned parents do not lose contact; providing support such as specific education offers for parents; and delivering counselling for family members.

In recent years, we have developed minimum standards to make visiting areas suitable for families, so that children will feel comfortable when they are visiting. Each penitentiary offers additional visiting hours for families, so that children get to spend more time with their parents outside of regular visiting hours. Regular personal contact like this can alleviate some of the strain.

In addition, the inmates can talk to their families on the phone and they can make video calls, which is of particular importance if they have no relatives living nearby.

We have developed children’s books for each prison facility, exploring the topic of incarcerated parents. In many of our correctional facilities, the inmates can take parental-skills classes, which will also be helpful for them once they have been released. Family members can always turn to representatives of the facilities when they have questions or worries.

When it comes to managing the transition between prison and the outside world for the families, we obviously cannot do this all by ourselves. We work together with other Ministries and departments and are always on the lookout for personnel with the necessary skills and experience. Moreover, we want to make sure that people outside of the penitentiary system get an idea of the reality of this scenario affecting the families of prisoners.

JT: Given our thematic focus in this issue of the Magazine, we’d like your insights on how this relates to Saxony, especially in light of its recent partnership with the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office in New York, USA.

Could you provide your perspective on the management of violent extremist and radicalised offenders?

KM: When the current State Government was voted into office, we all agreed that there cannot be any room for radicalisation in our correctional facilities. It is therefore necessary to develop special programmes focusing on prevention and de-radicalisation, as the penitentiary system must be able to deal with extremism thoroughly and professionally. In cooperation with other authorities and researchers in the field of criminology, we have created KUrteG, a policy plan for dealing with radicalised, terrorist, and extremist inmates.

This plan addresses practical matters, such as how to deal with violent extremists within the penitentiary, as well as ways of de-radicalising prisoners or making sure that they do not become radicalised while in prison. The policy plan consists of several individual parts, including training courses for members of staff, matters of security, and how to accommodate terrorists or people who have been imprisoned for politically motivated crimes. KUrteG also suggests ways in which the different authorities can better cooperate, and it addresses the topic of prevention. To deal with extremism in an effective way, we must identify radicalisation early on.

Lastly, is there a specific subject you would like to address that holds particular significance for you, and that you believe deserves heightened attention from national, European, and international communities in the field of Criminal Justice?

KM: Restorative Justice immediately comes to mind here, and we are very committed to developing it further. To me, Restorative Justice is an umbrella term for various ways in which victims, offenders, and third parties try to work out the situation among themselves if they feel they want to try it. This provides everyone with a more active role and may involve mediation. We are committed to the idea of giving victims more attention within the penal system, to find alternative ways towards justice and reconciliation.

We set up a Restorative Justice project in the correctional facility in Dresden in 2023. It involves training courses where prisoners learn to empathise with the victims of crimes, followed by talks between victims and offenders, and meetings in which they work towards a resolution. We are in the process of extending this project to another facility.

At the moment, we are still in the early stages of what we hope will be a long-term development. As of now, Restorative Justice plays but a very small role within the penal system. However, I see a lot of potential. The more experience we gather, the more advantages and long-term benefits of this approach will become obvious.

Unlike traditional methods of justice, Restorative Justice is less about retribution and more about meeting the needs of the people who are most directly affected. From their perspective, it is not so much about how the law was broken, but about how the crime has harmed them and how it affects their interpersonal relations. So instead of simply watching the state dish out punishment, it becomes a matter of individuals taking responsibility for what has happened. This makes Restorative Justice a real alternative to traditional retributive and repressive criminal justice systems.

Katja Meier

State Minister of Justice and for Democracy, Europe, and Gender Equality, Saxony, Germany

Katja Meier has studied Political Science, Modern and Contemporary History, and Sociology in Germany and abroad. She worked as a board officer for the Alliance 90/The Greens in Hesse. Returning to Saxony in 2010, she served as a policy officer for the party’s parliamentary group. In 2015, she was elected to the state parliament, where she held roles as a spokesperson for democracy, legal and equality policy. She is also a former member of the Saxon State Women’s Council. Meier has been serving as a Minister since December 2019.