Interview

Rómulo Mateus

Director-General of Reintegration and Prison Services, Portugal

What have been the central priorities since you took office at the Directorate-General for Reintegration and Prison Services (DGRSP)?

RM: I took office in February 2019 with a well-defined mission and some innovative ideas to be accomplished within a short period. However, nearly all our energies had to be directed towards protecting the people we were responsible for in response to the pandemic threat.

We manage a very sensitive system overseeing so many different people, including prisoners, the criminally insane, young people, and citizens serving community sentences; for this reason, we were inevitably going to suffer the impact of the pandemic crisis. Nonetheless, we managed to start some projects, with the main priorities being the reform of prison facilities, digital modernisation, juvenile justice, and prisoners’ mental health. We are also dealing with the scarcity and ageing of human resources, common in other public entities.

In addition to these myriad challenges, several incidents made the news linked to prisoners’ illicit use of mobile phones when I took office. Therefore, we had to undergo a critical examination of the communications we allowed inmates, and we concluded that the model of one telephone call per day for five minutes was obsolete and did not satisfy prisoners’ needs to maintain socio-affective ties.

We looked at models that had been adopted abroad, where telephone communications – maintaining the necessary precautions – are liberalised, with telephones installed inside the cells. So, we began a pilot experiment, installing telephones in the cells of certain prison facilities.

An initial concern was the instinctive objection from the community, so this issue required considerable time investment and debate with responsible authorities, the community and any interested stakeholders.

At the same time, we are very concerned with the not too rational distribution of prison facilities in the national territory, inheriting a legacy of disparate realities that are not always mutually compatible. We have several small prisons – the so-called district jails – that do not provide the system with much efficiency, and therefore we tried to look at a new model for managing these establishments. We had the idea of creating, as a pilot experience, a jail where there were only prisoners under an open regime, and we began to take steps to launch this reform as well.

We also had to take a leap of modernity in juvenile justice because it has inherited a model that was inadequate, very repressive, and restrictive of rights and the idea of approximating community life, which must govern life in educational centres.

At the same time, we had received strong reprimands from international organisations regarding mental health treatment for the criminally insane in our custody. At this level, we had to reinvent ourselves to achieve significant improvements in the living conditions that we provide these citizens. So, we had to work on several fronts, address various priorities, and change paradigms. Those were times of hope and commitment until suddenly COVID-19 reared its head in our country.

We relied on international scientific evidence indicating a decrease in the suicide rate of prisoners who have a phone inside their cell, a decrease in tension between guards and prisoners, and a reduction in mobile phone trafficking. Our experience indicates great satisfaction among the prisoners involved in little more than a year; there are now more than five hundred phones installed and an apparent decrease in mobile phone smuggling.”

Could you please give us more details about these transformation processes within the scope of mental health and open regime establishments?

RM: Mental health is an increasing problem, and the country cannot provide an adequate solution.

The DGRSP is responsible for approximately 500 criminally insane persons, and I became aware that many of them were concentrated in spaces offering little dignity in the only clinic that we have in a prison environment exclusively dedicated to psychiatry and mental health.

Our solution was to transfer these prisoners to a ward with excellent living conditions – an infrastructure created for the Drug-Free Unit of that prison unit but was not fully in use.

At the same time, because of the concerted policies that the Ministries of Justice and Health pursued, forty beds were made available at the Magalhães Lemos (psychiatric) Hospital in Porto.

The general principle is that these people should be in non-prison mental health units – only those with dangerous daily habits should be kept within the prison system. We also have wards in psychiatric hospitals in Lisbon and Coimbra and agreements with some specialised institutions.

In addition, we expanded the psychiatric clinic to a new wing. That allowed us to admit criminally insane persons waiting for an opening and prisoners with mental illness who were in regular prisons without the benefit of a therapeutic and recovery plan. At the same time, it was necessary to invest in more doctors, nurses, and operational assistants.

I am pleased that a recent visit by the National Prevention Mechanism resulted in praise for the new conditions that we can offer these patients.

That signals that, although faced with such a challenging pandemic – perhaps the most difficult time that the prison system has ever gone through – we have nonetheless managed to look after a very needy population. It should be noted that the criminally insane were among the first incarcerated persons to be vaccinated against COVID-19.

The system would need to invest in building a psychiatric clinic from scratch in Lisbon and reform the existing psychiatric clinic, which was modelled on an idea of a prison system that no longer measures up. However, we can hardly spare those resources at this time.

In addition, we have a renovation plan that envisages investment in halfway houses for the criminally insane, considering that when their mental health stabilises, they are no longer dangerous and should be returned to society.

The exclusively open regime prison in Torres Novas is a very motivating experiment that I would like to replicate. This prison had about 40 inmates – because it is a small district jail – and as many prison officers, which is not rational from the point of view of resource management, taking into account we have more than twenty other prisons of the same size.

This particular prison established very good relations with the community, particularly with local authorities, to the point of having about 30 prisoners outside, under an open regime. That is a wake-up call for social responsibility in the execution of prison sentences.

The open regime allows the prisoner to leave the prison facility for daily work without custody and return at the end of the day. With inmates who had already proven their trustworthiness in approaching normal community life, it was possible to transform this prison into an establishment directed to life outside the walls.

So, with far fewer security demands, we could transfer about half of the corrections officers to other facilities where they were needed. Moreover, we also reduced administrative staff. This is the possible model for the highly inefficient prison infrastructure we have inherited.

To what extent is digital modernisation a priority for the Portuguese correctional system?

RM: This Directorate-General performs an essential mission of the democratic state based on the rule of law, but I believe it has lagged behind the digital revolution. For example, prisoners’ processes are not digitised; we had an obsolete and insufficient computer system; we have a prisoner information system that does not meet the needs for rapid consultation, ideally shared with the courts to facilitate the swift exchange of information.

We have inherited a very backward model concerning innovations, for which the pandemic intensifies a pressing need. A fundamental government policy option in this context is to maintain people teleworking. However, this relies on adequate equipment, fast and stable computer networks and process digitalisation. We have much to improve in this area.

In 2019 and 2020, we invested €1,800,000 in purchasing computer equipment; this year, we are counting on investment of €800,000 in laptops, webcams, and network improvement. In educational centres, we have created conditions for remote communication between juvenile offenders and their families, and this proved crucial when visits were suspended because of the pandemic.

We have also developed these conditions in prisons, which are now equipped with devices that allow remote contact with the courts and inmates’ communication with family members.

We are trying to revive the pace towards digital reorganisation, which is underway although not progressing as quickly as we would like.

In the last five years, investment in electronic monitoring has grown by 124%, and we have a very robust and secure system. Interestingly, electronic monitoring risks falling prey to its success, as human and technical resources are already insufficient to meet the demand by the courts.

You have struggled for the installation of fixed telephone equipment in prison cells. What is the status of this measure, and what are the objectives of its implementation?

RM: This is a fascinating issue related to the search for a different and more humanised paradigm.

Initially, we implemented a pilot system for placing telephones in cells at the Linhó prison (male prison in the metropolitan area of Lisbon, which mainly houses inmates between 21 and 30 years old) and at the Odemira prison (small women’s prison).

Meanwhile, I received instructions to extend the project, and telephones are being installed in the cells of three other prison facilities.

For this project, we relied on international scientific evidence indicating a decrease in the suicide rate of prisoners who have a phone inside their cell, a decrease in tension between guards and prisoners, and a reduction in mobile phone trafficking.

Our experience indicates great satisfaction among the prisoners involved in little more than a year; there are now more than five hundred phones installed and an apparent decrease in mobile phone smuggling.

At the end of 2021, we will make a final assessment and, if the solution proves to be reliable, safe and an asset to the prison system, our goal will be to implement it in all prisons. It should be mentioned that installing telephones in prison cells will not add a financial burden to the state.

A concession holder selected through a public tender will bear installation costs, and inmates will pay for the calls. Inmates will only be authorised to call numbers that the prison administration agrees to meet scrutiny and security requirements.

What is your assessment of sentence management using electronic monitoring, and, in your view, is there growth potential for alternatives to imprisonment?

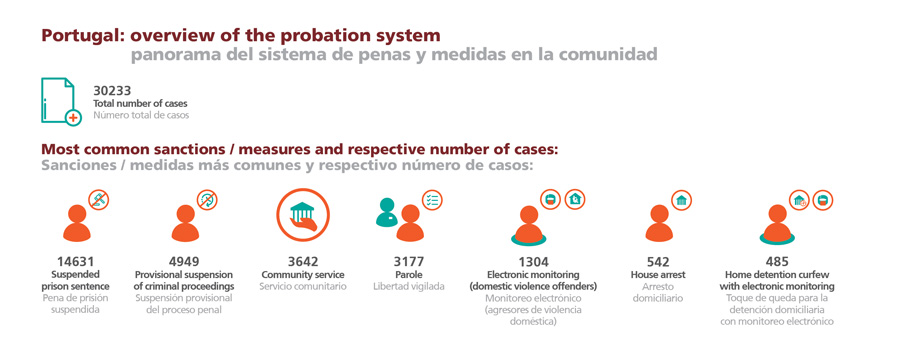

RM: We currently have about 2,500 people under electronic monitoring. Quite possibly, if we did not have this alternative model, those people would be inside the prison system.

The cliché – that a prisoner costs the state around €50 per day, while a person under surveillance costs a maximum of €10 – is accurate and has repercussions on the state’s resources to allocate to the DGRSP.

In the last five years, investment in electronic monitoring has grown by 124%, and we have a very robust and secure system.

Interestingly, electronic monitoring risks falling prey to its success, as human and technical resources are already insufficient to meet the demand by the courts. Whilst this is a sign of success and the confidence that the courts place in the system, there is an urgent need to reinforce the human support of this model.

We are vigilant on this matter, the authorities are aware of it, and I know they are concerned.

I only see advantages in electronic monitoring: it spares offenders from the penitentiary experience – with its harmful aspects – it is safe, saves the state money, and has immense growth potential.

At the moment, 53% of persons electronically monitored are so-called domestic violence offenders. Domestic violence is a scourge to which the country has recently awoken and has severe repercussions throughout the system: we have more than one thousand prisoners in the prison system due to domestic violence, i.e. almost 10% of all prisoners.

But the answer cannot just be custodial and judicial; it must also be cultural.

We managed to remove around 2,000 inmates from the prison system, 700 of them under the extraordinary administrative exit permit. This measure has been a great success, and its framework law is flexible, it allows such permits to be granted even today.

JT: The Covid-19 pandemic has brought great challenges to prison organisations.

Given the restrictions resulting from the pandemic crisis, what kind of measures have been implemented in Portugal?

RM: It is not easy to announce to prisoners that their level of seclusion will increase and that their contacts with the outside world will be restricted even more.

We already have a year of experience managing the prison system with COVID, and it is only fair to acknowledge the civic and committed way the prison population in Portugal accepted the many restrictions that we had to impose on them; those who stayed within the system and those who were able to leave and who are still under our responsibility.

We realised very early on that it would be necessary to remove prisoners from the prisons. Quarantine spaces were needed to treat those who fell ill; we feared that an outbreak of COVID-19 could lead to the disease multiplying with lightning speed, and this was confirmed by the outbreaks we faced.

The various social, political, and legislative players understood the urgency of this measure and we were thus able to relieve the pressure that would exist within the prisons, if and when COVID hit.

The President of the Republic pardoned cases of obvious human need, legislators authorised an amnesty for small sentences with two years remaining, and the most unusual measure was the so-called extraordinary administrative exit permit.

The latter allowed those prisoners who already had a routine of authorised regular exits to wait at home for the end of the pandemic. We managed to remove around 2,000 inmates from the prison system with these three measures, 700 of them under the extraordinary administrative exit permit.

Indeed, it involved risks because no one could guarantee that, once at home, the inmates would not go out into the street or re-offend with some criminal act, although the history of these people gave us some security.

In truth, the number of incidents involving these inmates is practically nil. They remained at home under the supervision of the social reintegration teams, which was spread over repeated home visits and was essential for us to pursue this measure.

Most of the prisoners who were released under the extraordinary exit permit have since moved on to parole, a sign that they meritoriously complied with the difficult rules imposed on them. This measure has been a great success, and its framework law is flexible, i.e., it allows such permits to be granted even today.

Once relief had been obtained, and space was created within the prison system, we had to adopt measures to bring back visits for prisoners as soon as possible. We spent around €300,000 on acrylic booths in the visitation rooms so that face-to-face visits could resume, albeit with pre-scheduling and some limitations.

At the same time, we increased phone calls: instead of one five-minute call per day, prisoners could make three calls. It’s less than I would like, but a legal framework limits us.

Additionally, the instructions were to liberalise and facilitate virtual contacts and virtual hearings as much as possible, and they have been used abundantly. Some inmates prefer virtual visitation because it spares relatives a trip to the visitation room, where a physical barrier restricts them.

Therefore, the focus of the adopted measures was essentially to protect prisoners; despite having to subject them to quarantine on return, we never cancelled authorised exits because we know how vital those exits are for the emotional balance of prisoners and their families.

Rómulo Mateus

Director-General of Reintegration and Prison Services, Portugal

Rómulo Mateus has been a public prosecutor since 1986, and during his career, he also held the office of Public Prosecutor in Kosovo under EULEX between 2013 and 2018. Previously, between 2002 and 2009, he served in the Directorate-General for Prison and Probation Services (DGRSP) as Chief Inspector in the Audit and Inspection Department. At that time, he was appointed to a Council of Europe working group as an expert on pre-trial detention and prison management. Currently, he is a public prosecutor at the Lisbon Central Criminal Courts, leading the DGRSP under appointment by secondment.