// Interview: Danijela Mrhar Prelić

MSc., Director of the National Probation Service, Slovenia

JT: What was the procedure for setting up a National Probation Service in Slovenia and how did you become involved in it?

DP: The establishment of the National Probation Service in Slovenia arose mainly from the recognition of a need. Although this recognition had already taken place in 2006, there were no major developments in this regard due to a lack of political will. But in 2015, the Ministry of Justice urged the Government to review the reorganisation of community criminal sentences and to establish the service. On the one hand, we had to follow EU directives, and on the other hand, there was a strong awareness that short prison sentences have negative consequences for the offenders.

So, in July 2015, the Government decided that the Ministry of Justice should prepare an action plan for that purpose. Thus, the Minister of Justice established an inter-ministerial working group (WG) composed of members of various Ministries (Justice, Internal Affairs, Labour, Family and Social Affairs), the Supreme Court, the Office of the State Prosecutor General, the Faculty of Law, the Institute of Criminology and the Prison Service. Given my expertise and my experience in the correctional field, and because of my PhD research (I am currently researching the topic of recidivism), the Minister invited me to take the lead.

Initially, the WG had over twenty members, but I organised a group of five people to lead the drafting of the action plan. We conducted research which showed that we were not using community sentences as much as we could: although prisons were overcrowded, 55% of prisoners were serving a prison sentence up to two years. Research also pointed out problems in communication between the authorities who oversaw the enforcement of alternative sanctions; there were issues at the decisional level and overall the number of alternatives was scarce.

In the face of such reality, in only five months’ time, we developed the action plan, which was presented to the Minister right away. Then we prepared all the documentation for the Government who accepted it without changes in July 2016.

In September 2016, we began to prepare the Law on Probation that was then sent to the other ministries involved. After governmental approval of the Probation bill, it then required the Parliament’s approval. The Law on Probation was accepted by the Parliament in May and entered into force in June 2017.

After an extensive legal process – which ended at the end of 2017 – the Slovenian Probation Service was officially established on the 1st of January 2018 and on the 1st of April 2018 our probation units started with work and had received 488 cases social welfare centres. The National Probation Service is really the result of hard work from a group of people who really believed in it.

JT: What role has international cooperation played?

DP: We have received great support from various partners, and I take this opportunity to thank them very much for all the advice and help they have provided in preparing the action plan and in establishing the Slovenian Probation Service.

We collaborated with Norway, Ireland, Northern Ireland, the Netherlands and very strongly with Croatia. The latter is also a country that was part of the former Yugoslavia, so we have a very similar criminal justice reality.

We visited the probation services of all those countries, we had many meetings with their staff and Croatia was involved in the training of our officers. We are also very much connected with the CEP – Confederation of European Probation. Cooperation made our work easier and all our partners have advised us very constructively.

JT: The National Probation Service became responsible for the enforcement of house arrest and community service, sentences that were formerly overseen by the court/police and social welfare centres, respectively.

What exactly are the duties and responsibilities of the National Probation Service, and to what extent has the change from the former framework to the new one been peaceful?

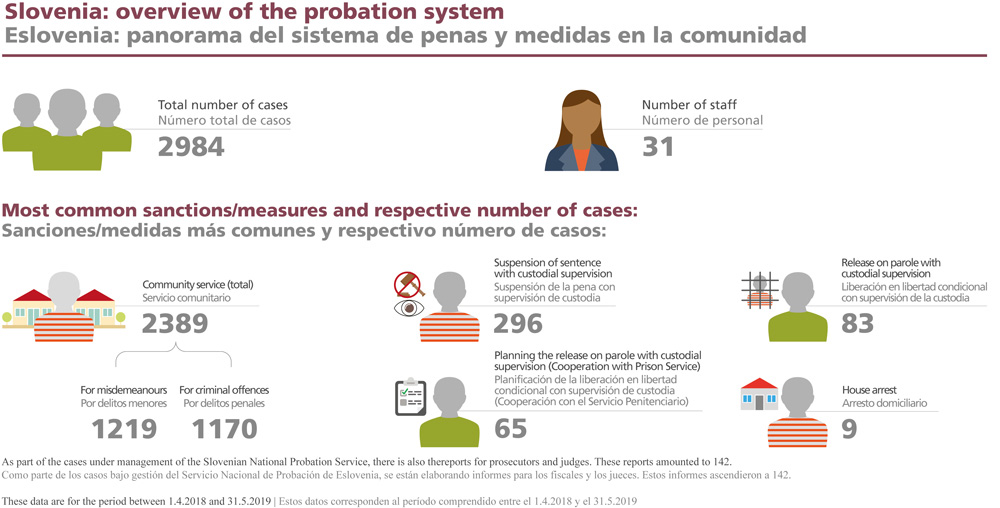

DP: The transition was very smooth because all relevant Ministries were involved in the development of the action plan and in close cooperation. The National Probation Service is responsible for preparing reports for prosecutors in the process of resettlement; we prepare the reports for prosecutors in the process of suspended prosecution; we are entitled to compensate and settle the damage within the process of suspended prosecution; we prepare the reports for supporting the courts in the decisions about the kind of sentence that should be implemented; we also oversee the suspended sentence with custodial supervision, the release on parole with custodial supervision, the house arrest and community service. Moreover, the Probation Service cooperates with the Prison Service regarding the planning for release on parole under custodial supervision.

Our Service enhances the resort to alternative sentences as a replacement of short prison sentences; we provide assistance to persons under probation, in accordance with the criminal code, in identifying and eliminating the causes that influence the act of committing criminal offences, we support them by addressing personal distress and problems, arranging living conditions and establishing acceptable forms of behaviour.

We started with 488 cases and by mid-May 2019 we were overseeing 2,869 cases! We didn't expect such a caseload in the first year (…)

JT: What are the main challenges facing the Slovenian Probation Service?

DP: We started with 488 cases and by mid-May 2019 we were overseeing 2,869 cases! We didn’t expect such a caseload in the first year, as people usually need time to adjust.

We followed the advice of other probation services in Europe so we went to all courts and prosecutors to explain our mission, our responsibilities and tell them that we would collaborate in a positive way. I think we’ve done a good job of presenting the service and we believe that’s why the community’s sentences are increasing, and we expect numbers to continue to increase in the future.

In the first year, we thought we would have about 1,500 to 2,000 cases, so we figured we would need 33 officers, but we were only assigned seventeen. That caused an overload. So, mid last year, I asked for more staff and received strong support from the Ministry of Justice. In April 2019, the Government finally gave the green light to the recruitment of 30 officers. It will take a few months to train and integrate them, but in the end, our mission will be much easier.

I recognise that the quality of service has not been at its maximum due to staff shortages. The most challenging units were Ljubljana and Maribor – the largest cities in Slovenia. The other three units were in general able to work according to the agency’s vision. We had to accept that we could do a better job if we had more employees. Quality is one of our most important goals.

If we compare the current data with past data, we see a very large change in alternative sentences. The use of alternative sanctions and measures in cases of criminal offences is increasing.

In 2017, misdemeanours accounted for 57% of all alternative sanctions and 43% were for criminal offences, whereas, in 2018, 63% of alternative sanctions concerned criminal offences – that’s a 20% increase from one year to the other. We still do not know for sure whether this improvement and increase are a consequence of the creation of the National Probation Service, but, in a few years, I think we’ll know.

April 2018

JT: According to the Resolution on the National Programme for the Prevention and Suppression of Crime for the period 2012-2016, cited in a book chapter that you wrote, “alternative sanctions in Slovenia are rarely applied, there is a high percentage of recidivism, and there is a lack of scientific research on criminal matters.” (Source: Mrhar PRELIĆ, D. (2019). Prisoner Resettlement in Slovenia. In: F. Dünkel, I. Pruin, A. Storgaard and J. Weber, ed., Prisoner Resettlement in Europe. Oxon: Routledge). How is the Probation Service supporting solving those challenges?

DP: The problem is that Slovenia has no research in the field of recidivism, that’s why I’m trying to finish my PhD. The current numbers of recidivism are based on a definition that considers any crime recommission regardless of the time that has elapsed since the end of the sentence.

By this definition, about 45 to 50% of all prisoners are re-offenders. My research is not yet complete, but I already have data to conclude that, in the case of female offenders, according to the broader definition, recidivism is around 24%.

However, if we narrow the definition to consider that recidivism is the commission of a crime within two years after release from prison – which is the most commonly used definition in the EU – this rate drops by 13%.

It is unfortunate that, in Slovenia, no one has focused on the need to research recidivism, nor on the process of prison release and social reintegration. The findings of other researchers show that the most common reasons for recidivism are unemployment, homelessness, addictions, and unfavourable social environments.

Electronic monitoring will not only be the responsibility of the probation service, but also of the police and prisons, so it needs to be developed together.

JT: Historically, the rehabilitation and reintegration of offenders in Slovenia has always had the participation of many entities, not only governmental but also from civil society.

To what extent has this reality remained the same after the National Probation Service was created?

DP: We relate to over eight hundred non-governmental organisations (NGOs), all over Slovenia, that can help us enforce sentences of community service. Although we have such a wide network of NGOs, we are still facing challenges because, due to the lack of public transport and the state of development of some parts of the country, some regions end up becoming distant. So, we, in the central unit, are working to expand the network of partnerships.

Another challenge is finding organisations that can support offenders who have addiction problems; in fact, there are not enough entities in the country that can provide psychiatric support to our clients. We relate to psychiatric hospitals and health care institutions, however, in some regions, these institutions are scarce or even non-existent. We always try to find support organisations as close as possible to where the offender lives, and we are collaborating with local communities, on a daily basis.

the then Minister of Justice and State Secretary, April 2018 (From left to right: Emanuel Banutai,

PhD; Simona Svetin Jakopič, MA; Dragana Stojmenović; Barbara Starič Strajnar; Danijela Mrhar

Prelić, MA; Goran Klemenčič, MA (Minister of Justice); and Darko Stare (State Secretary).

JT: What technologies do you have in place at the National Probation Service (or that you are planning to use) to better fulfil the mission of the Service? And, how do you envisage the implementation of an electronic monitoring system in the country?

DP: Now we are using a case management system since all the governmental institutions in Slovenia have a programme for case management. And we also have self-developed forms and tools for the day-to-day work of probation officers.

Last year, prior to the start of our activity, we prepared extensive documentation for all units of the Service, including a 150-page book, on all the work procedures and tools available to officers. We also rely heavily on Excel and its functions.

Currently, we are developing an information system – which will be called ProbIs – for whose development we are using EU funds. It is expected to be concluded by the end of 2020, and at this stage, we are preparing all the documents, technical data, specifications and details to begin the development of this IT system, which will be very much based on our already existing self-developed tool.

By the end of 2019, we plan to begin the development of an RNR model also through EU funds; of course, that will be with the help and drawing from the experiences of other EU countries.

When we were preparing the action plan for setting up the National Probation Service, we didn’t focus on electronic monitoring because the first need was to reorganise the enforcement of community sentences and achieve efficiency in what we would do.

In any case, our understanding is that electronic monitoring will not only be the responsibility of the probation service but also of the police and prisons, so it needs to be developed together. In the future, I do think that there will be a need for the development of that type of system in Slovenia. Nevertheless, although I believe that electronic monitoring is a very useful tool, we should never forget that we are working with people and that nothing should replace human intervention or touch.

In the future, I think that we also need to focus on and be prepared for the prevention and countering of radicalisation and extremism.

JT: It is well known that violent extremism and radicalisation processes tend to be driving factors in terrorist threats.

To what extent and in what way is the Slovenian Probation Service involved in the prevention and countering of radicalisation and extremism?

DP: Thanks to international cooperation, we are aware of a number of threats to the level of violent extremism and radicalisation that can occur in correctional contexts including the probation service, but so far, fortunately, there have been no such cases in Slovenia. This does not mean that we are not aware that they can happen, which is why we are working with other international counterparts through participation in meetings, and we are also members of various working groups in preparing a suitable environment when working with extremist or radicalised offenders. In the future, here in Slovenia, I think that we also need to focus on and be prepared for this topic, in collaboration with the police and the prison service.

//

Danijela Mrhar Prelić began her career as a counsellor in juvenile correctional facilities and was then invited to lead the female prison in Slovenia. At the beginning of 2016, she took the lead of the inter-ministerial group in charge of preparing an action plan for establishing the National Probation Service, by invitation of the then Minister of Justice and later she became the director of the Slovenian Probation Service. She is a teaching assistant of Social Pedagogics in the field of Criminology and Penology, at the University of Primorska. Moreover, she is developing her PhD thesis in Criminology, with research into recidivism and reoffending in Slovenia.

Advertisement