Interview

Ahmed Najmaddin Ahmed

Jurist and Director-General of Social Reform, Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, Kurdistan Region, Iraq

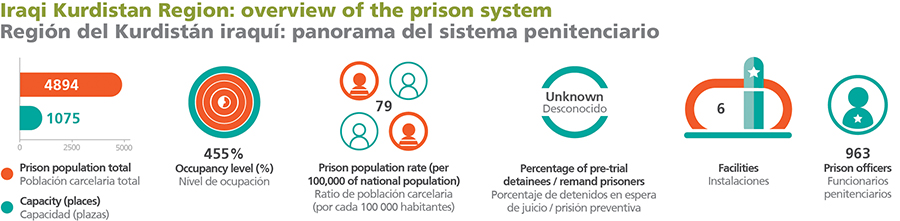

The prison system in the Iraqi Kurdistan region faces substantial challenges, primarily due to geopolitical and security fragilities. Radicalisation, violent extremism and prison overcrowding are concerns that the Director-General has to deal with daily. In this interview, he gives us an account of the prison system’s reality. The priorities are assessing risk and promoting a rehabilitative environment, a mission for which they need international support.

Could you please give us an overview of the Kurdistan Region’s criminal justice system, including a characterisation of the correctional system?

AA: Concerning criminal procedures in Iraq, there are generally two phases: the preliminary investigation, which is the judicial fact-finding stage, and the judicial litigation stage, meaning the main trial.

The criminal process is investigative; the investigating judges lead the judicial fact-finding phase. They have broad investigative powers, including responsibility for the evidence-gathering process and holding formal hearings for suspects and witnesses.

Based on the available evidence, investigating judges can dismiss a case, close it temporarily, or refer it to a court for the main trial. When the case moves from the investigative court to the main trial, the file created by the investigating judge is used as an official record.

The trial judge leads the trial process in each case and takes responsibility for the hearing and adjudication of the case, where the investigating judge collects primary evidence. Court sessions are usually relatively short.

The role of the Public Prosecutor in Iraq is primarily administrative. It includes monitoring judicial procedures and places of detention to ensure the legality of the procedures.

Judgments of the Court of First Instance can be appealed to the Court of Cassation, which includes reviewing the case file. The Court of Cassation automatically reviews death sentences or life imprisonment. The Juvenile Care Act applies to persons under the age of 18.

The Kurdistan Regional Government operates under the 2006 Anti-Terrorism Law (No. 3). The anti-terrorism law applied in the Kurdistan region criminalises terrorist acts including “the use of violence to spread terror” and “any act with terrorist motives that threaten the region’s security or damages public property”.

The sentence ranges from death to life imprisonment. There has been a de facto moratorium on the death penalty since 2008. Currently, there are 409 people under sentence of death in Kurdistan’s region correctional centres.

Our correctional system is legally framed by the 1981 Law nº 104, and the 2008 Social Reform System Act of the Kurdistan Regional Government.

Our Correctional Directorates are divided into three cities. We categorise prisoners by gender and age: women are separated from men, and adolescents are separated from adults.

Offenders under 18 tried by the Juvenile Court will serve their sentence in the juvenile correctional centre until 22. If they still have time remaining on their sentence after that age, they are transferred to an adult correctional facility.

In adult corrections, classification is based on crime type and risk level. For example, terrorist offenders have been separated from drug users and dealers, murderers from thieves, and so on.

Moreover, under the authority given to the Ministry by the Reform Law, the Minister of Labour and Social Affairs has issued several instructions covering different subjects. One of these directives allows temporary absences for convicted prisoners to visit their families, provided they meet a set of pre-established conditions.

Other directives have to do with using force to restore order among prisoners, instructions on the ranks and uniforms of front-line staff who have confrontations with the inmates, and special directives regarding prohibited goods in inmate cells.

The Director-General has the authority to issue administrative guidelines for correctional staff. In this context, the Director-General issued guidelines concerning officers’ duties and the mechanism for solitary confinement for disorderly prisoners, among other topics.

We are now drafting a solid bill that includes all instructions, guidelines, and texts from previous legislation formulated after being amended.

This bill provides for the creation of separate Directorates for Women and Youth and a Directorate for the Abolition of Drug Addiction and Mental Illness, considering Law No. 1 of 2021 on Drugs and Mental Health in the Kurdistan Region.

JT: Approximately one year ago, there would have been around 450 ISIS prisoners in the Kurdistan Region (Source: Rudaw, 11 Nov 2021).

What is the situation concerning prisoners linked to terrorist groups, and what are the main challenges of such a reality?

AA: With the rise of ISIS terrorist organisations, the Kurdistan region, like every other part of Iraq, has been threatened by extremist terrorists. Terrorists began to target security agencies and civilians through bomb attacks and riots.

The terrorists formed organised units in the Kurdistan region and throughout Iraq. Their intelligence sources are still active, and some have reorganised. Sadly, women, children and other civilians are among the victims of terrorism.

We currently have 2,300 terrorist prisoners in the Kurdistan region correctional centres. Most prisoners are from central and southern Iraq. For the most part, these prisoners are serving long sentences, including a proportion of women and youth. While rates are lower than for adult men, we have many juveniles who have been involved in ISIS’s extremist actions. This reality negatively impacts communities, families, and the correctional system.

As a correctional institution, we lack prior experience in dealing with offenders convicted for terrorism and classifying and treating them. Our priorities are to assess their extremism risk level, establish a segregation protocol, and provide a rehabilitation and reintegration process.

In addition, it is critical to identify appropriate training which may be an influential factor in changing their thinking and behaviour. Ultimately, all these factors will impact their own safety and the protection of the prison facilities where they’re serving their sentences.

The large influx of terrorism-related offenders to our centres has significantly contributed to prison overcrowding. The latter is especially true at adult male facilities in Erbil, Sulaymaniyah and Duhok, where most convicted terrorists are placed.

The total maximum capacity of these establishments is 900 inmates. Nevertheless, they now house between 1300 and 2200, which means that sadly we had to allocate more than twenty to thirty individuals in cells intended for eight inmates.

We lack prior experience in dealing with offenders convicted for terrorism and classifying and treating them.

Our priorities are to assess their extremism risk level, establish a segregation protocol, and provide a rehabilitation and reintegration process.

What are the prison system’s needs to better deal with and prevent terrorism, and to what extent is external support and cooperation, namely from international organisations such as the US Department of State and UNODC, important at this level?

AA: The Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) is committed to the rehabilitation and reformation of offenders.

However, unlike advanced countries, we still do not have adequate management experience in this process.

The international community is concerned about the sovereignty of human rights and their protection. We, too, want to work in line with the Nelson Mandela Rules.

We are aware that if our institutions’ work and management processes do not meet these standards, we will have an incomplete and humiliating rehabilitation philosophy. Furthermore, community safety will face threats.

Extremism intensified after the fall of the former Iraqi regime. Later, both Al-Qaeda and ISIS became threats on an international level. This led to more and more terrorist offenders coming to our prisons.

To successfully deal with these inmates, we need to assess their level of risk. Risk assessment is one of the shortcomings that threaten our correctional centres. We therefore need international support and cooperation, particularly from the US Department of State and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).

We must train our staff in legal, security, administration, leadership, crisis management, contingency plans and the prevention and reduction of threats in the prison context.

It is also imperative that we provide training and rehabilitation programmes to prisoners and that we deal with them according to international counter-extremism laws. We believe that this kind of threat will continue because of the geopolitical turmoil in our region and the influential causes of extremism and terrorism.

That’s why we need to continually prepare ourselves in the face of terrorism-related threats. We cannot face this alone. We will have weak and inadequate results if we do, as we have neither sufficient human capacity nor advanced technology.

Therefore, international cooperation supports us with the necessary provisions to be more confident and increase our morale.

Over time, we have had external support. After 2009, we benefited from capacity building activities through EUJUST LEX-Iraq (European Union Integrated Rule of Law Mission for Iraq). This crisis management mission improved our correctional institutions based on European practices.

It allowed us to deepen our knowledge on the protection of human rights in the custodial context, techniques for dealing with inmates, and other critical topics. This cooperation was insightful and helped us move forward.

Furthermore, I have participated in many conferences and dozens of training courses and workshops, both regionally and internationally.

The European Union, the Swedish Prison and Probation Service, UNICEF, and UNFPA have played an essential role in our support over the years.

Recently, the workshops that the UNODC conducted in Erbil in November-December 2021 increased our hope and aspirations. And those workshops certainly enhanced our staff’s skills. This initiative was a great start.

As we advance, we will do our best with UNODC to continually bring about positive change within the framework of International Law and the UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners.

Risk assessment is one of the shortcomings that threaten our correctional centres. We therefore need international support and cooperation.

What other challenges does the correctional system face? And what progress has your Directorate-General been able to achieve amidst the region’s particular geopolitical and security fragilities?

AA: Because offenders convicted of terrorism are dangerous, they require strict security and specific programmes. Security measures are especially critical during inmate activities due to the danger of escape.

We are talking about organised groups that try to take advantage of the moments when we provide health, sports, vocational training and even when we distribute meals, to generate chaos.

For example, when Mosul and Makhmur were captured, terrorist prisoners were able to threaten the prison governor and staff. Terrorist prisoners are generally psychologically unstable. Their families cannot visit them, and some do not have a telephone number or an address.

Most of them would need pocket money for daily expenses, but they don’t have anyone to meet those needs. And the Regional Government is already burdened with providing them with the facilities and related services. Nevertheless, despite tensions and complications, I can briefly mention some of the achievements of our correctional system.

First of all, education is one of the most significant achievements of our prisons. We have around 400 inmates continuing their education: 29 in college, 100 in high school and 265 in elementary school. In total, one hundred teachers teach in the prison system.

Protecting, caring for and treating our detainees as to their physical and mental health is another achievement that we are proud of. All six prisons in the Kurdistan region have a clinical centre, where we provide comprehensive health care and have doctors daily.

Our medical clinics include laboratories, x-ray equipment, pharmacies, and inpatient wards. And if an inmate needs further treatment, we will refer them to the city hospital to receive the necessary treatment.

Moreover, we have a social and psychological support unit managed by social workers. One of the most significant achievements of such a unit has been holding seminars, training, and cultural series for many ISIS affiliated juvenile prisoners, the so-called Ashbal al-Khalifa (the cubs of the Caliphate).

The activities consist of dissecting and extracting ideas of religious extremism and violence. With this initiative, we were able to get many young people to abandon their extremist views.

The achievements that we made in the legal field include the provision of lawyers, conditional releases, and temporary releases so that inmates can visit their families at home.

I would also like to highlight the topic of vocational training. In all our reformatory units, inmates can learn AC maintenance and repair, blacksmithing, carpentry, barbershop, decoration, painting, women’s handicrafts, electrical equipment repair, agriculture, and planting, etc.). Many prisoners work and earn a living.

Additionally, we do after-release monitoring. We help released juveniles to find a job and in some cases we even provide them some financial support to start a small project.

I am also pleased to say that we have outstanding achievements in sport and physical education, with prisoners taking part in various rounds, training and sports competitions such as football, volleyball, table tennis, chess.

Regarding staff training and development, we have opened several courses, seminars and training workshops for our employees. With such initiatives, we have managed to improve their work.

Furthermore, we were able to provide proper security for our correctional centres through cooperation with the Ministry of the Interior, which is also working hard to protect our facilities’ perimeters.

The special programmes we are implementing at our centres serve government policies to reduce crime and violent extremism. In this way, by helping to reduce the threat of terrorism, we are promoting and ensuring public safety in our country.

JT: According to their official website, the Kurdistan Regional Government is committed to an ambitious mission: good governance, digital transformation, relations with the Federal Government of Iraq, foreign relations, and the strengthening of security forces.

To what extent and in what ways does your Directorate-General

contribute to each of the government’s mission areas?

AA: Like any government, the Kurdistan Regional Government provides the budget to meet the needs of the correctional system.

The ISIS outbreaks of occupation and attacks in our region led to economic and security deterioration, negatively impacting government administration.

There were delays in the full payment of civil servants’ salaries, including prison governors and other correctional staff. Nevertheless, all have continued to work tirelessly, with a spirit of sacrifice and support for the government, given the circumstances.

The correctional system’s main contribution is preparing the inmates to return to the community and their families as law-abiding citizens.

We work to lessen the criminality mindset and rehabilitate all those in our custody, especially those convicted of terrorism and working with Al-Qaeda and ISIS, which pose direct threats to the government and society.

The special programmes we are implementing at our centres serve government policies to reduce crime and violent extremism.

In this way, by helping to reduce the threat of terrorism, we are promoting and ensuring public safety in our country.

Moreover, we are trying to rehabilitate and reintegrate all our inmates according to international law and the Nelson Mandela Rules, which support community safety in general.

Ahmed Najmaddin Ahmed

Jurist and Director-General of Social Reform, Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, Kurdistan Region, Iraq

Ahmed Najmaddin Ahmed is from Iraqi Kurdistan. He holds a master’s degree in Public Law and has worked for nearly three decades in different fields. In 2009 he began his duties as Director-General of Social Reform under the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs of the Regional Government of Kurdistan. His previous position was as a management consultant at the Ministry of Health.