Interview

Vincent Van Quickenborne

Minister of Justice, Belgium

Belgium’s Justice System faces complex challenges such as prison overcrowding, high recidivism rates, and the pressing issue of organised crime.

In this exclusive interview with the Belgian Minister of Justice we explore his valuable insights into the country’s approach to criminal justice, particularly focusing on the penitentiary system.

What are the main challenges facing the State in the field of justice?

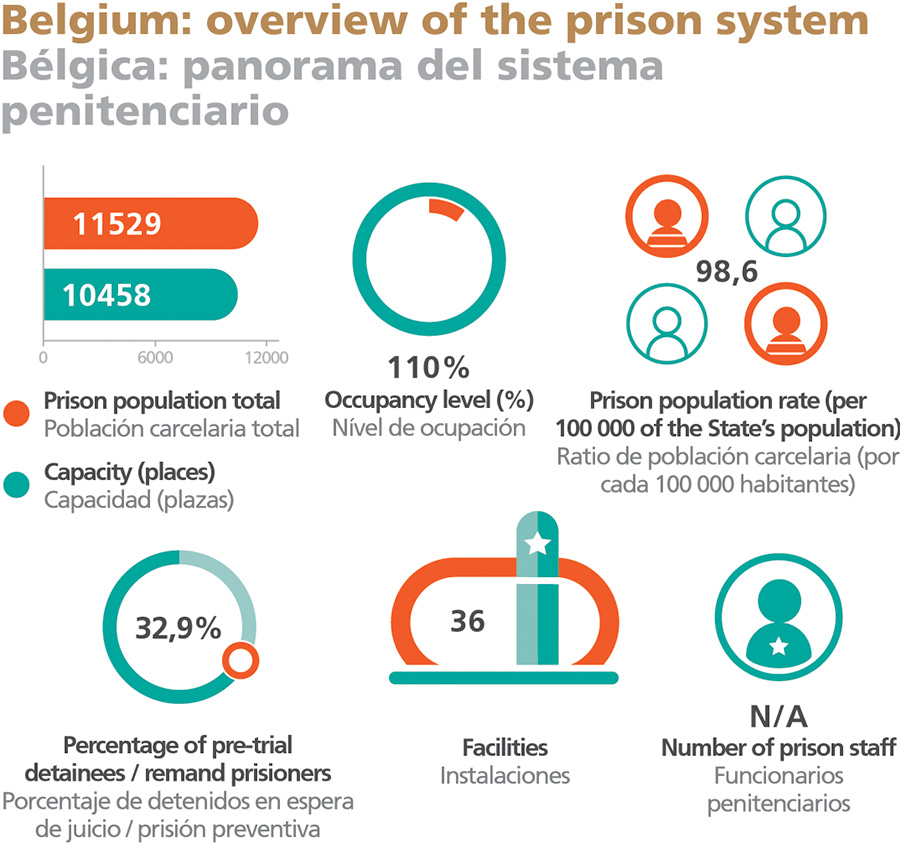

VVQ: In Belgium, detention is administered across 36 prisons and a small yet growing number of small-scale “detention houses” and “halfway houses.” On this day, the Belgian Prison Service facilities house a total of 11,529 inmates yet the real capacity is 10.458. The problem of overcrowded prisons has persisted for decades in our country.

Upon assuming office three years ago, I wanted to address this pressing challenge head-on. However, it’s important to recognize that our system faces not only prison overcrowding but also a daunting 70% recidivism rate among released prisoners. Furthermore, we must urgently improve the care provided to those with mental health needs while in our custody.

To tackle these critical issues, we have implemented a three-pronged approach. A significant step in our reform effort has been the revision of our sentence execution laws for terms shorter than three years. This overhaul has led to the establishment of new small-scale detention centres specifically designed to provide personalised guidance to individuals serving shorter sentences. Moreover, we have transitioned the role of traditional prison officers towards that of detention counsellors, with an increased focus on rehabilitation. Over the past year, we’ve successfully recruited 460 such detention counselors, who work tirelessly to assist inmates in preparing for their reintegration into society. This strategic shift is expected to have a substantial and positive impact on reducing recidivism rates.

At the same time, our commitment extends to improving healthcare services for those inmates with mental health or psychiatric care needs. These comprehensive measures underscore our determination to provide the necessary support and care to reduce reoffending rates and foster rehabilitation, and these measures should structurally alleviate prison overcrowding at the same time. We are dedicated to ensuring a more human, safer and more effective criminal justice system for all.

To what extent was Belgium able to mitigate overcrowding with the opening of new facilities, and what other measures are being taken to address the lack of prison places?

VVQ: For over four decades, Belgian prisons have been grappling with chronic overcrowding, and the historical approach of simply adding more prison capacity has proven ineffective. It is estimated that only around 20% of the prison population truly necessitates complex and costly high-security infrastructure. Prolonged incarceration without specific guidance tends to worsen recidivism, as individuals treated inhumanely in prison often return to society with the same mindset.

Belgium is shifting away from expanding traditional prison capacity and moving towards smaller-scale detention houses where inmates can receive the support and guidance needed to facilitate re-entry.

This includes finding suitable employment, acquiring new skills for the job market, and learning essential life skills such as personal finance management and securing appropriate housing. Successful examples from other countries demonstrate a positive impact on reducing recidivism rates, where rates have come as low as 30%.

The first small-scale detention house of this kind opened more than a year ago in my own home city, with 75 residents who have served short sentences passing through it so far. Daily coaching in small living groups focuses on their social integration. Some inmates attend external training programmes, such as forklift driver certification with almost guaranteed employment, while others take a bicycle to work in the kitchen of a popular restaurant each morning, with their employer committed to keeping them employed after their release.

The capacity of these planned detention houses varies but always remains below 60 residents per location, divided into living groups of 12 to 15 individuals. Currently, two detention houses have opened, and seven more are in progress. The short-term goal is to establish 15 such houses across the country, as their effectiveness is most pronounced when working with inmates from their own region. In the long term, the aim is for 80% of the kind of detainees currently housed in prisons to be accommodated in these facilities, though this transformation will take several years.

To further alleviate prison overcrowding, the new penal code, currently being debated in parliament, emphasizes alternative forms of punishment over traditional imprisonment. This legal reform represents a shift away from the nineteenth century idea of prison sentences and/or fines as the default outcome for all criminal offences. Instead, it allows for tailor-made sentences like mandatory psychological treatment, road offense prevention lessons, courses in aggression management, and community service as viable alternatives, ultimately reducing incarceration. In combination with the construction of new prisons set to open soon and the opening of additional detention houses, it is expected that the total number of inmates will decrease in the long run.

Until recently, sentences lasting less than three years were not executed. This policy was implemented many years ago to combat prison overcrowding. However, starting in September 2023, these sentences are once again being carried out in prisons. While this decision might temporarily strain prison facilities, it is anticipated to have a positive impact in the long run. The use of detention houses for shorter sentences and providing active support for reintegration within smaller living groups helps reduce the likelihood of repeat offences among this cohort.

JT: You have described the new Haren Prison as a prison village capable of promoting a new perspective on detention, more humane and focused on the empowerment and reintegration of detainees.

Can you tell us more about the rehabilitation and reintegration approaches enabled by the new prison facilities? What is the role of these advances within the broader reintegration strategy for the penitentiary system?

VVQ: The Haren prison, opened just last year, represents a significant step forward in modernising and strengthening the Belgian prison system. Unlike traditional prisons that focus solely on security and control, Haren takes a more progressive approach, emphasizing personal detention guidance for both short and long-term inmates.

This forward-thinking facility, accommodating 1,190 inmates, diverges from the conventional star-shaped prison design. Instead, it adopts a “prison village” concept, where residents are housed in separate living units of approximately 30 individuals each. Within these units, inmates enjoy greater freedom of movement throughout most of the day. They can coexist, dine, and engage in activities within their unit’s communal area, even cooking for themselves in the shared kitchen.

A noteworthy innovation at Haren is the introduction of inmate key-badges, programmed to open cell and circulation doors. This means that inmates can move within the premises without constant physical supervision, enabling participation in workshops or visitation.

While security remains a top priority within and outside the prison, Haren recognises that an overemphasis on restrictions and control can undermine the autonomy and sense of responsibility of inmates, which is crucial for successful reintegration into society.

The detention counsellors and security assistants work in tandem to provide a balanced and dynamic security environment. They perform security procedures, handle crisis situations, and serve as points of contact for inmates, colleagues, and visitors. Although the operation within these units differs from that of a detention house, it allows for a more tailored and collaborative approach with each inmate, focusing on their individual needs and working toward a better personal future after release.

Additionally, in Haren, a Secure Clinical Observation Center will be established, capable of accommodating up to 30 inmates for extended observation conducted by a psychiatrist, resembling the Dutch Pieter Baan Centre1.

This programme spans six weeks, during which the forensic psychiatry teams can gather more comprehensive information about individuals involved in cases with psychiatric context. This enhanced assessment facilitates a more accurate evaluation of the potential risks posed by the inmates.

JT: A worryingly growing issue in Belgium is organised crime, a threat which you have identified as “the new terrorism”. Among the measures to fight the phenomenon, Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, France, Italy and Spain have agreed to strengthen cross-border cooperation efforts.

Can you share your perspective on the phenomenon and its significance within the priorities of the Ministry?

VVQ: Belgium, along with neighbouring countries has recognised the need for enhanced cross-border cooperation to combat organised crime, especially drug trafficking. This cooperation signifies the collective commitment to address the transnational nature of criminal networks.

The city of Antwerp's status as the world's second-largest container port and a primary entry point for cocaine into Europe adds a critical dimension to the problem. Criminal organisations exploit the port's strategic location, leading to violent conflicts and criminal activities within the region.

Organised crime groups involved in drug trafficking in our country are predominantly international in scope. They encompass South American drug cartels, the Albanian mafia, Moroccan criminal syndicates, and the ‘Ndrangheta, among others. The leaders of these groups often seek refuge in foreign countries, making their apprehension a complex challenge.

But the net is closing on these criminal gangs. The police and judiciary are taking strong measures and succeeding in shutting down an increasing portion of their activities. We have introduced a comprehensive package of strict control measures to safeguard port access, regulate the use of port equipment using biometrics, strictly limit the availability of sensitive data, and improve personnel screening, similar to security measures at airports. Additionally, there has been an increase in the deployment of police, investigators, and customs resources to combat organised crime at all levels. A newly appointed national drugs commissioner ties all these operations together.

In some countries, the violent nature of these criminal groups is evident through incidents like attacks on magistrates, police officers, and journalists. Such acts of violence have also been witnessed in other countries, including the Netherlands where a lawyer and a journalist were shot in the street in broad daylight. These actions underscore the seriousness of the threat posed by organised crime.

I, myself, narrowly escaped a kidnapping attempt last year. For weeks, me and my family were forced to seek refuge in a safe house, and, even to this day, we remain under continuous police protection. But this shows that we are making progress, that we are succeeding in hunting criminals down. And we can only do this through international cooperation. It takes a network to defeat a network.

There is increasingly better collaboration between Belgium, the Netherlands, France, Germany, Spain, and Italy. We urgently need to bring this collaboration to a full European level through the EU.

Our current collaboration extends to American law enforcement agencies, governments of Central and South American countries and even to nations still offering safe havens to suspected criminals.

Tackling organised crime is a long-term challenge. While progress is being made, the fight is ongoing, and we remain committed to addressing this threat with the goal of achieving success. I have no doubt we will win this in the end.

To what extent is organised crime inside prison facilities a concern in Belgium and how that issue being tackled?

VVQ: The influence of organised crime within prison facilities is a concern, as it is in many other countries. To combat this issue, several strategies are in place, and lessons are drawn from experiences abroad. Belgium looks to countries such as the US, Italy and the Netherlands to gain insights into effective measures for addressing this challenge.

One major concern is the smuggling of narcotics and mobile phones into prisons. Efforts are made to strengthen security measures to detect and prevent the introduction of these prohibited items.

A particular challenge in some older Belgian prison buildings is the practice of throwing prohibited items like weapons, drugs, and mobile phones over walls and fences. While the throwing of illegal items like weapons and drugs has always been punishable, there was no penalty for throwing phones for instance. The new penal code in Belgium will make the act of throwing objects over prison walls and fences a punishable offence in itself. This is a proactive measure to deter such activities.

Moreover, we are continuously working on improving security within prison facilities, including the installation of advanced surveillance systems, increased staff training, and better screening procedures for visitors.

Effective intelligence gathering and information sharing among law enforcement agencies, both inside and outside prisons, play a crucial role in combating organised crime within prison walls. Collaboration with external agencies and police forces is essential to disrupt criminal networks.

But, while security measures are critical, addressing the root causes of criminal behaviour and promoting rehabilitation and reintegration of inmates are also part of the strategy.

Providing inmates with opportunities for education, vocational training, and counselling can help reduce their susceptibility to organised crime.

1 A forensic psychiatric center located in the Netherlands. It is responsible for assessing and treating individuals who have been accused or convicted of serious crimes and are deemed to have a mental disorder that may have contributed to their criminal behavior. This centre conducts comprehensive psychiatric assessments to determine the mental state of the individuals, supporting the legal system make decisions about the appropriate legal measures.

Vincent Van Quickenborne

Minister of Justice, Belgium

Vincent Van Quickenborne has been the Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Justice and the North Sea in the Belgian government since 2020. He was the youngest Senator in Belgian history, from 1999 to 2003. He was later responsible for the enhancement of administrative efficiency, first as Secretary of State for Administrative Simplification, and then as Minister for Entrepreneurship and Simplification until 2011. Before taking on the role of Minister of Justice, he has previously served as Pensions Minister. Vincent Van Quickenborne remains actively involved in local governance as the mayor of the city of Kortrijk, where he currently resides.