An inspiring look at the projects and contributions of leaders in the Justice sector

Guest

Pedro das Neves

CEO, IPS_Innovative Prison Systems |ICJS Innovative Criminal Justice Solutions

Pedro is the CEO of IPS_Innovative Prison Systems – a research, advisory and technology development firm specialised in justice and correctional Services – and executive director of ICJS Innovative Criminal Justice Systems in North America.

He has worked on public administration reform for more than 20 years and on Criminal Justice Innovation Systems in different countries, spearheading groundbreaking projects that reimagine how correctional systems operate, making them smarter, more efficient, and above all, more humane.

In this interview—with a special episode host and experienced sector leader, Sam Erry—we’ll delve into Pedro’s insights, explore his vision for the future of corrections, and discuss the role of AI in shaping tomorrow’s justice systems

Special Host

Sam Erry

Sam Erry is a seasoned transformational leader with over 13 years senior executive experience in service delivery modernisation, public-private partnerships, and relationship management.

Sam held various top-level positions in the government of Ontario, Canada including as Deputy Solicitor General (former Deputy Minister of correctional services).

After his career in the public service, Sam was Executive Vice President at Connexall, where he developed a strong executive team and enhanced Connexall’s value-proposition in the global healthcare market.

Sam is currently Executive Advisor to the Executive Command Team of the York Regional Police Service as well as Executive Advisor to the School of Leadership Studies, Royal Roads University (Victoria, BC). He is also a Strategic Advisor to IPS Innovation Prison Systems and of ICJS Innovative Criminal Justice Solutions Inc in North America.

This is a multimedia interview

How did you first get into working with prisons and probation systems? What drew you to this field?

A personal commitment born from chance

Pedro das Neves: I had my first contact with prisons when I was 16. I was a volunteer working with other friends from a Catholic group that came to visit prisons and inmates. And I did that until I was 18 or 19.

And then, after that period when I entered university and until I started working, I never thought of coming back and being a volunteer or working in a prison. But when I began my professional career as a management consultant, just by chance, there was an opportunity to develop a project with the Portuguese Prison Service.

That was the first project that we ever did. It was focused on leadership development and operational standards, involving over 200 people, mainly in management roles within the correctional service. After that, an even larger, more transformative project followed. From there, the work expanded—first to Romania, then to other European countries, and to other parts of the world, including the Middle East, South America, and North America.

Could you share how your international work began and highlight some interventions that were meaningful in your life and the lives of others?

Partnerships for criminal justice reform

PN: I think most of the interventions have been really meaningful to me because they directly impact other people’s lives. I could talk about some of these projects we have developed in Portugal, but also in Romania, starting in 2008. That was a period of significant transformation in the Portugal, particularly within the correctional service.

It was a tough period due to major reforms—economic, financial, and fiscal—where at one point, for instance, the salaries of correctional officers were cut, and the International Monetary Fund intervened in the country. We were trying to change the way the correctional service was working, but at the same time, we were also experiencing the side effects of this transformation happening in the country.

Despite these challenges, it was amazing how the professionals that we were working with managed to introduce changes in the way that they worked, and ultimately, to improve the conditions of incarcerated people. That intervention was very special to me, having had the privilege of supporting those changes is something that really touches me even today when I think about it.

I can also mention interventions in South American countries, where detention conditions are very difficult, and professionals face serious challenges. When we think about prison conditions, we often focus on what inmates endure—and rightfully so. Ensuring dignity for detained individuals is essential. But we also have to consider the conditions for the professionals working in those environments.

For example, I’ve worked on projects in countries like Guyana, where the situation was really difficult for both inmates and professionals working in the prison service, and in Brazil, where similar challenges exist.

So I always feel that we are very privileged, especially in some European and North American jurisdictions, even though we have a lot of problems, of course, and still a long way to go. But it’s quite amazing what people in resource-strapped systems can achieve through their commitment. Those are some of the interventions that have had the greatest impact on me throughout my career.

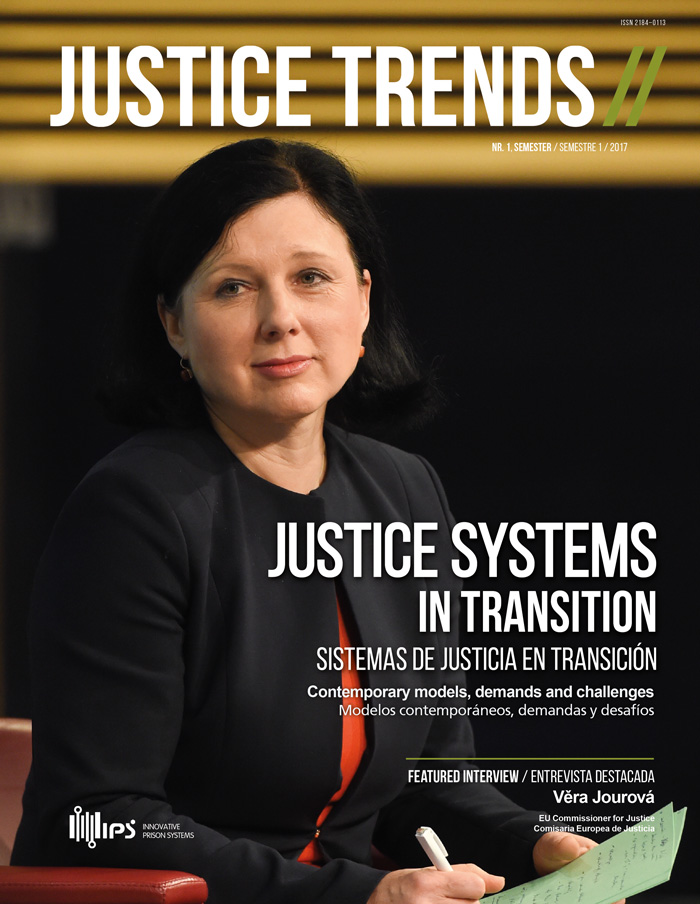

Can you share what inspired you to create the JUSTICE TRENDS Magazine, and how it contributes to the global dialogue on justice and corrections? What do you hope readers take away from it?

Connecting justice leaders across borders

PN: The initial idea behind the JUSTICE TRENDS Magazine was to foster dialogue and share best practices. As we moved from country to country in our professional activity, I realized that—especially at the time—many jurisdictions had no idea of what was being done elsewhere, sometimes even within the same country.

There were states or provinces unaware of each other’s initiatives, missing opportunities to adopt good practices, or countries in Europe that didn’t know what their neighbours were doing, even though they were struggling with the same issues.

So when we thought of creating the JUSTICE TRENDS Magazine, it was mainly an instrument to share knowledge and to share practices among the different jurisdictions. We do that by interviewing the key actors that were in fact producing change in the different jurisdictions.

There were states or provinces unaware of each other’s initiatives, missing opportunities to adopt good practices, or countries that didn't know what their neighbours were doing, even though they were struggling with the same issues.

PN: We invite heads of corrections to talk about what they’re doing, and Ministers of Justice to talk about the policy changes that they’re trying to introduce. We interview and bring articles from renowned experts in the sector to share their insights.

Unlike an academic journal, we try to keep our articles short so that decision-makers can quickly grasp the key points. The goal is to highlight what a certain practice entails, its benefits, and, if readers want more details, they can reach out directly to the author.

Ultimately, we would like to help jurisdictions learn from each other. We want readers to ask: What is happening elsewhere that we could adapt to our reality? How are other countries tackling similar challenges, and what can we learn from them? At the same time, what have we done that is interesting that we can share with others?

I think that to some extent we have accomplished that. We receive letters from heads of service from different countries whenever we launch an edition, expressing their gratitude for receiving the magazine.

We have to thank our partners and sponsors as well, who make it possible for us to share the print edition of the magazine for free in 120 countries.

You started your career focusing on training and organisational change, and now you’re deeply involved in corrections, digital transformation, and the use of artificial intelligence in criminal justice systems. How did this transition happen? What inspired you to expand your work into these areas?

Adapting, learning, and leading

PN: I think it’s been a natural path, at least for me. I’ve always been very curious about how technology affects our lives and can bring a positive impact. I started working in training and change management, working to change the organisational culture of public institutions.

As we start to introduce technology in our daily lives and to support our operations—including bringing technology to incarcerated persons—I was really curious to understand what would be its impact in these settings. So for me, it’s been quite a natural path to follow, exploring how we can use technology to improve the way we operate and the impact it can generate in the people that we work with.

Over time, my focus expanded to the technology field, not only to explore technology and its impacts, but also to understand my own team.

PN: My background is in a completely different area—I graduated in sociology.

When I started working in corrections, I was, of course, familiar with issues related with inequality, the victimisation of certain groups, with social exclusion, and other related concepts. But I didn’t have much knowledge in criminology, so I had to study, and that’s what I did.

As my interests shifted, I moved more into the public policy field. I completed a master’s degree in that area and started a PhD in public policy, that I never finished. Over time, my focus expanded to the technology field, not only to explore technology and its impacts, but also to understand my own team.

I work with a team of technology developers, including a Chief Technology and Information Officer, developers, and project managers in the technology field. At times, I couldn’t really understand some of the technical discussions, so I felt the need to go back to school. I took executive courses and even postgraduate studies in the technology field to bridge that gap.

I started in areas like digital transformation because I wanted to grasp the core concepts. I was already familiar with digital transformation from my experience in the consulting world, implementing large technology projects in telcoms, for instance, back in the 2000s. But I wanted to go deeper and really understand the processes and the technologies, so I did studies in digital transformation.

More recently, I’ve also focused on studying the use of AI in different sectors, so that I could also understand how can AI impact corrections. That has been my main area of interest lately.

The HORUS 360 iOMS is being recognised as a unique and innovative solution. Could you explain what makes HORUS stand out and how it addresses the needs of correctional systems today?

Evidence-based offender management

PN: We started looking into offender management quite a long time ago—it’s been more than 10 years now since we first began thinking of the development of such a solution.

The main reason for this is that, talking with different jurisdictions, they would consistently tell us that their existing solutions would not fit their real needs. Sometimes, the issue was the system itself, and other times there was resistance from the vendors to adapt the solutions that they had. Most of the systems that are out there are legacy systems designed to answer the questions we had 15 or 20 years ago.

PN: At the time, the focus was to know how many inmates were in custody and who they were. There was less concern about questions about how to reduce recidivism or promote desistance from crime. Put simply, the data these systems are collecting does not help us to respond to these questions that we have nowadays, nor the ones we will have in the future.

That means that new systems need to collect new types of data, and we need to reflect on questions that we will have in the future, and collect data that will help us respond to those questions. That is exactly what we have been doing with HORUS.

HORUS is not just a solution that covers the offender journey from intake to release—even beyond custody, when someone is serving a sentence in the community. It was also designed to capture a wide range of data, including information from other systems, like CCTV, inmate communication platforms, and self-service systems. HORUS integrates this data into the offender management system, applying AI and machine learning algorithms to make sense of that data and support decision-making for correctional professionals and administrators.

I believe that part of the positive response that we are having from jurisdictions results exactly from the fact that correctional administrators see that the data we collect, and the way we structure it for analysis and reporting to support decision-making, is aligned with their needs. And that is the difference from other solutions that are out there.

What do you think are the main challenges correctional services are facing today? And what strategies or innovations do you believe are essential to address these challenges effectively?

Rethinking corrections for a changing world

PN: The challenges are, of course, different depending on where we are and where we stand. It’s completely different if we are talking about Africa, the Middle East, or Asia, or if you are in North America or in Europe.

But we came from a pandemic not long ago, and we still see its impact on correctional services. Everybody is still facing some constraints as a result of the economic problems that different governments had after the pandemic. On the other hand, we haven’t really learned from, and normalised some of the innovations that were introduced during that period.

During the pandemic, because of isolation measures, many jurisdictions brought in tools to support the communication between inmates and their families. In several countries, after the pandemic, those instruments were removed—whether phone calls, video calls, or telemedicine solutions. We did not take advantage of that momentum that the pandemic generated in order to normalise the use of those technologies and those instruments.

Additionally, in many jurisdictions, we are dealing with overcrowding and overincarceration. Again, during the pandemic, what happened was that a lot of people were released. However, we didn’t see an increase in the crime rates because of that.

This suggests that we probably had people in prison who could have been the community serving their sentence. But, after the pandemic, many systems reverted to their previous sentencing practices, leading to a steady increase in prison populations once again. In many countries, systems are dealing with overcrowding and bad detention conditions.

I believe that some of the solutions that we may think of might have to do with reducing the prison population, using alternatives to incarceration, such as community-based measures.

PN: If you think about the pressure that overcrowding brings to very often old facilities, we see that many countries are dealing with serious challenges. I believe that some of the solutions that we may think of might have to do with reducing the prison population, using alternatives to incarceration, such as community-based measures. In many cases, these have proven to be more effective than an incarceration measure.

Of course, I’m not saying that people should not go to prison. What I defend is that we should only send to prison people that really need to be there, when that is justifiable. Which means that whoever has the conditions to serve a sentence in the community without putting public safety at risk, then we should decide for those measures.

For this to happen, we need to invest in risk and needs assessment that support decisions that ultimately affect peoples lives, not only in the inside but also in the community. Technology can help here too. If we have data collected by proper offender management systems, we can support our decisions based on that data. And that does not happen in all jurisdictions. This is an area where we need to evolve.

Another challenge that many jurisdictions often struggle with has to do with staff training and retention. First of all there is the issue of lack of staff, because it’s more and more difficult to attract people to work in corrections. Then, once we have people working in corrections there come the questions of how do we train them, how do we capacitate them, and then how do we retain them in that profession? This is a challenge and an area where we have been very much committed to working with different jurisdictions.

Read more about the topics of this interview