// Interview: Sebastian Schulenberg

Director General of Prison and Probation, Senator for Justice and Constitutional Affairs, Bremen, Germany

JT: Could you please give us a picture of Bremen’s correctional landscape and talk about the main axes in which the Senator of Justice and Constitutional Affairs intervenes?

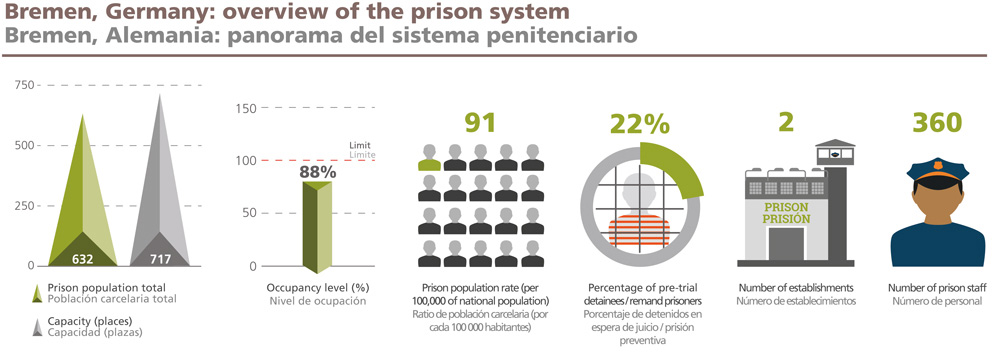

SS: The Bremen correctional system is organised to work towards two central goals, the first one is enabling offenders to lead a crime-free and socially responsible life, and the second is to protect society from further criminal acts. To achieve this, we rely heavily on fines and community-based sentences instead of prison sentences. Bremen has a prison population rate of 91, which is relatively lower than other European Union members. However, there is still room for improvement, when comparing it to other German federal States.

We believe that our prison policy is progressive; for decades, we have been pursuing a prison policy that is focused on an open prison regime, following the ideas of resocialisation, and taking responsibility and care for the needs of each individual prisoner.

We consider prisoners to be our fellow citizens and our future neighbours, so it’s really all about respectful treatment. At the same time, we’re challenging the prisoners to develop as individuals. Having challenging therapeutic programmes for offenders and working with them is essential to our prison regime – and not just locking them away. In Bremen, we have a slogan: “The first day in prison is the first day to prepare for the time after prison”.

Even though Bremen is the smallest German federal State, we manage two prisons (one in the city of Bremen, and the other in Bremerhaven), and we oversee all kinds of prison regimes and custodial sentences. In addition, the Senator of Justice and Constitutional Affairs is responsible for the financial decisions concerning disciplinary measures, the overall prison system strategy, and non-custodial sentences.

JT: To what extent do you think that the small size of the prison population makes the work easier and whether it poses fewer challenges in terms of correctional management and innovation?

SS: While we have a relatively small prison population, we must make fast bureaucratic decisions. We are familiar with the problems on site, so the information gets passed on to the enforcement practice quickly, which makes us very flexible.

On the other hand, having a prison population of 650 people (with a maximum of 717 places) stretches our capacities. Just to give you an example: we have to run a regime for female prisoners although we only house about 20 of them.

As Director-General I’m also responsible for the wellbeing of my staff, so I would very much favour a scenario with only 500 inmates. We need highly specialised staff for relatively small units of inmates, which is a challenge by itself, but this also means job enrichment and satisfaction because our staff have the opportunity to work in different prison regimes.

In terms of innovation and management of change: only recently, during a conference in Berlin, there was a statement by a colleague from Ireland. He said he could really tell that Bremen is a Hanseatic city, which I found nice because we really are.

To think outside of the box, to seek partnerships with our neighbours, to share our best practices, to trade ideas and to learn from each other is in our DNA. In Bremen, we allow trial and error, we involve our staff in change management, and I think we are built on firm ground if we trust institutional and individual expertise.

For example, lately, we finished the “Prison 2020” project in which we involved our prison staff from all different hierarchical levels. In a larger institution, with many administrative units, such a thing would not have been possible.

JT: Can you mention some of the current main challenges in the correctional system?

SS: The rise of refugee-seekers in Germany, which brought many juvenile offenders from Northern African countries four years ago, was for us an unknown and challenging situation. In addition, radicalisation and extremist offenders are an issue these days.

Another challenge is the fact that we have 40% of prisoners from a foreign background. Our prison staff is faced with a prison population that speaks multiple languages, so the first challenge is communication and by this I don’t mean only words and vocabulary but also non-verbal communication, which is different from one culture to another.

So, our concept of resocialisation might not fully fit inmates from non-European cultures, due to different personal and social experiences and different cultural meanings. One example is that in our prison system every inmate has his/her own room – which I, as a European, would find comforting. But especially our juvenile offenders from North Africa tend to feel that being left alone in their room is a way of isolation and punishment.

However, being close to staff really helps to be aware of problems and facing all kinds of challenges. Being the Director-General and meeting with prison staff quite often – I’m not far away in a Ministry but rather it’s a ten-minute ride by train – allows me to know what the general mood is, how everyone feels about changes, their opinion about projects, as well as their health issues and level of satisfaction.

So, we’re not just doing theoretical work here at the Ministry; I know most of the staff, they know me, and regular contact with them makes things easier.

JT: Technology and technological modernisation tend to play a key role in modern justice systems/correctional services, and we imagine that reality is not different in your jurisdiction. What role does the Bremen Senator of Justice and Constitutional Affairs play in that matter?

SS: Our Prison Act sends a clear and strong message: life in prison should be as approximate as possible to life outside. So, if there’s technology outside the prison, generally it has to find its way into prison.

Twenty years ago, it was unthinkable that prisoners would have a TV in their rooms and in Bremen now every prisoner has got access to three basic channels, so they can watch sports and the news, and that partly allows them to remain part of society.

Then there are telephones; all prisoners can make phone calls through secured telephone lines, although inmates under pre-trial detention conditions are only allowed to call certain people after a security check, but it allows them to keep in touch with their families, which we believe is important. And the latest technological development we are thinking about implementing is tablets; we’re researching how we can make use of tablets in prisons for daily routines, to give prisoners a schedule, to give them access to certain websites, which would have been pre-checked, for example.

Technology also plays a key role in terms of security. Some of the technologies that we have in place include anti-drone systems and video-visiting systems, and we also use Skype. Having a significant percentage of our prison population from a foreign background, those communication technologies allow them to keep in touch with their families abroad. Then, we have electronic monitoring, of course.

We need to provide both the financial resources and the facilities so that prisoners can use technologies, and we are shaping the Law to match the current needs concerning this topic – Law must always follow the technological change.

Prison policies should enshrine the principle of normality; that life in custody should resemble life outside prison, and it is the Senator of Justice and Constitutional Affairs who is responsible for that. We really see prisoners as fellow citizens – not an object of State security. They have their individual rights and we need to help them find their way back into society.

//

Dr Schulenberg is Director General of Prisons, Social Services and Alternatives to Imprisonment at the Senator of Justice and Constitutional Affairs of the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen, Germany, since 2016. He has been a lecturer in European Law and State Liability Law at the University of Bremen for the last seven years. His resumé includes three years as a judge and three years of research in Law. He holds a Law degree, an LL.M from the University of Cambridge (UK) and a PhD from Bucerius Law School in Hamburg, Germany.