Interview

Jaime Tapia

Advisor on penitentiary issues to the Basque Government

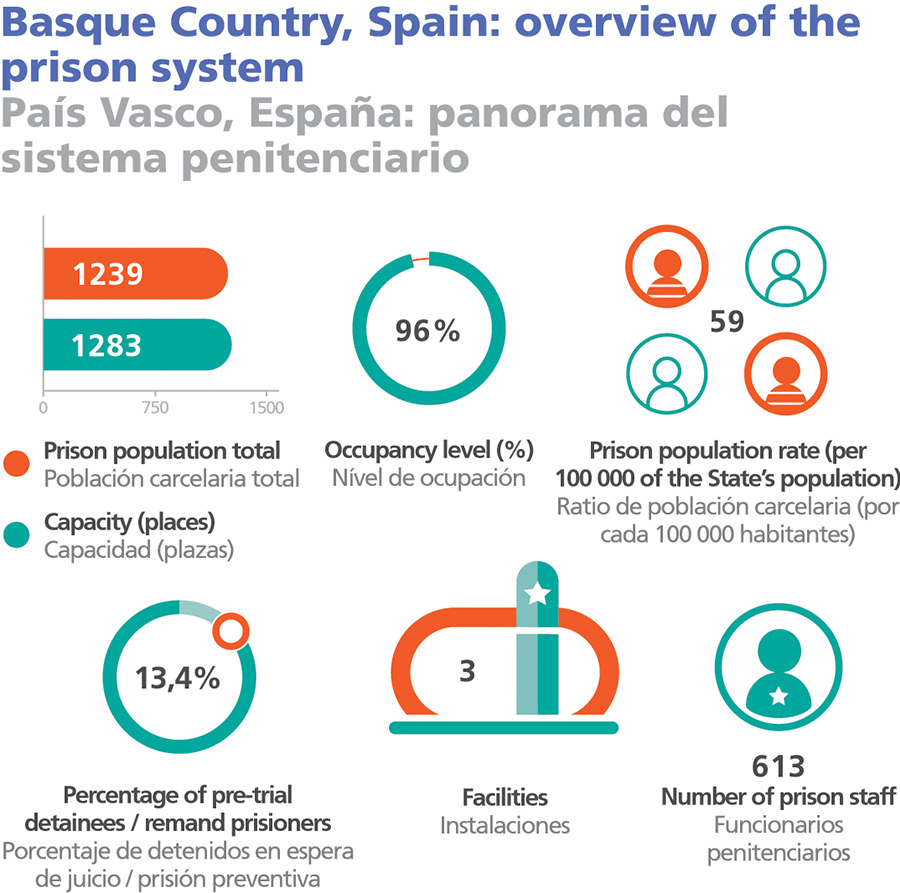

In October 2021, the Basque Country (Spanish autonomous community also known as Euskadi) took over the management of the prisons on its territory, becoming the second autonomous community after Catalonia to assume this responsibility.

The Department of Justice of the Basque Government has expressed its firm commitment to the social reintegration of inmates. Under the leadership of Magistrate Jaime Tapia, a comprehensive strategy for the new prison model has been drawn up. The aim of this strategy is to provide penitentiary institutions with a humanised approach that respects the rights and dignity of persons deprived of their liberty. The system aims to provide inmates with the necessary tools to successfully reintegrate into society after serving their sentence.

This vision, which is often difficult to reconcile with public opinion’s punitive mindset, is even more complex in this context, given that the prison population in the Basque Country includes convicted members of ETA, a Basque nationalist terrorist organisation.

What have been the priorities of the Basque Government’s Justice Department since it took over the management of its prisons? What achievements would you highlight in these two years?

JP: Since we took over the management of prisons in the Basque Country, we have established several priority lines, which are reflected in the document Bases for the Implementation of the Penitentiary Model. The first priority is equality and gender mainstreaming. We have worked to remove obstacles to equality between men and women in our institutions. In addition, we have set up a mothers’ unit to enable mothers to be with their children, and we have promoted women’s access to semi-liberty (third degree). Today, our system is gender-sensitive.

Another fundamental line concerns the children of prisoners. We consider it crucial to take into account the best interests of children in the field of penal execution. For this reason, we have implemented a project of psycho-social and socio-educational care for minors, with the aim of minimising suffering and maintaining family relationships, which are usually severed and destroyed as a result of imprisonment.

Improving the situation of people with serious and incurable illnesses, including those over the age of 70, was another area of action we envisaged. We have also addressed mental health and addiction issues to minimise the negative impact and provide the necessary support.

Another important area is to improve relations and coordination with the judiciary, the bar associations and all those involved in prison management.

Issues related to staff working in penitentiary institutions, which requires a quantitative and qualitative increase, was another key line of action. We are now in the final stages of publishing new vacancy notices, and this will probably have some effect as early as next year. Our approach is to involve more professionals in treatment, such as psychologists, social workers and educators.

Finally, I would like to emphasise the objective of promoting both work in the prison environment and labour integration through vocational training. We have increased the number of working inmates and improved their wages.

To achieve this, we have set up a special unit to increase the number of productive workshops and cooperation with companies.

JT: The plan for the implementation of the penitentiary model in the Basque Country proposes strategies such as allowing short sentences to be served in semi-liberty and promoting alternative measures to pre-trial detention or for people with illnesses.

What challenges and results have you had in implementing these strategies?

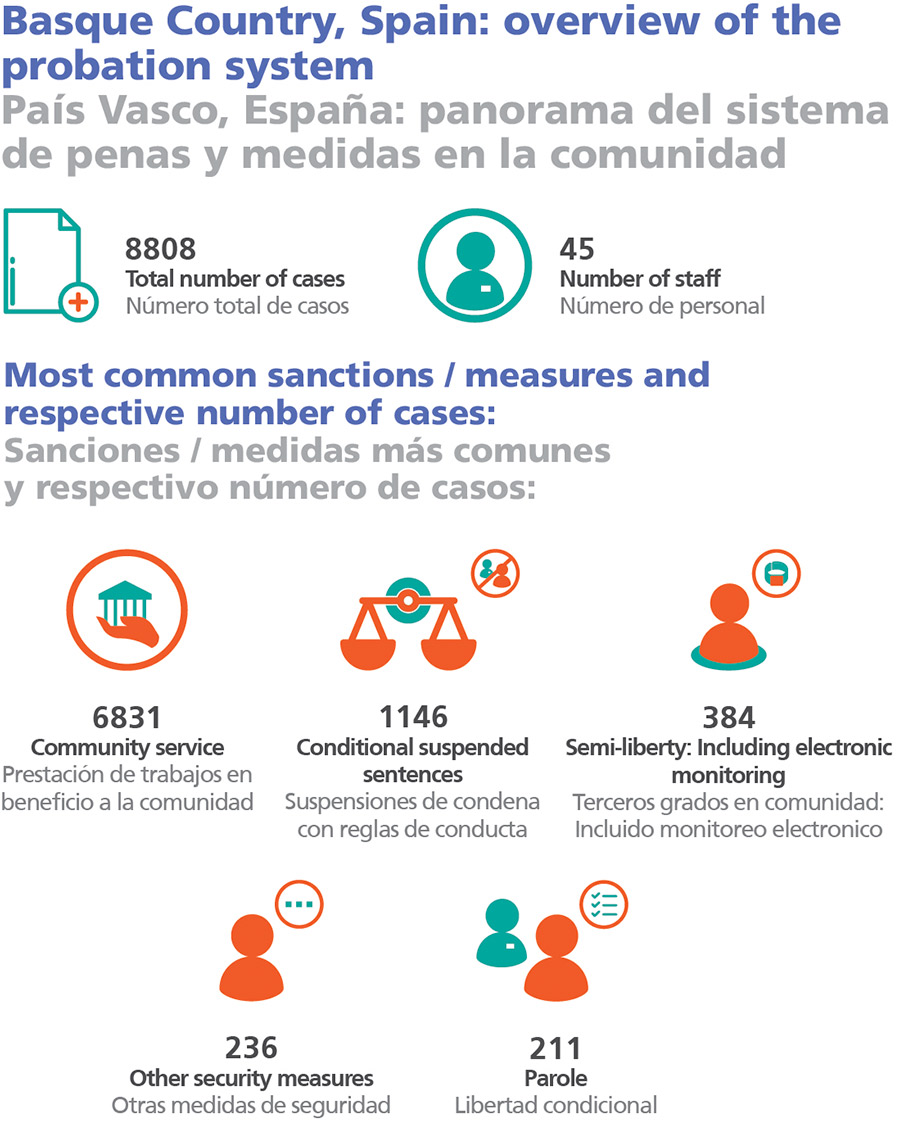

JP: Indeed, one of the fundamental objectives of the plan was to improve and increase the number of people serving their sentences in semi-liberty or through alternative measures. However, we are constrained by the penitentiary and penal legislation in force in Spain as a whole. Nevertheless, we have made significant progress.

We have the advantage over certain parts of the country in that judges and prosecutors trust and have a positive perception of alternative sentences and measures, and use them whenever possible. In this respect, the implementation of alternative measures has improved significantly, in particular by improving the ratios of people responsible for their implementation. Framework agreements have also been signed with public institutions to take in persons subject to these measures.

With regard to custodial sentences, which judges have no choice but to impose, there has been a significant increase in the number of people serving their sentences in semi-liberty, known in Spain as third-degree or conditional release. This includes rapid access to semi-liberty regimes through electronic monitoring systems, especially after the experience of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Currently, around 30% of men and almost 40% of women are serving sentences in semi-liberty using this control system. Evidence shows that people serving sentences semi-liberty have a lower reoffending rate than those serving full sentences in prison.

Our aim is for 40% of sentences to be served in semi-liberty. This would make it possible to achieve the purposes of the sentence without resorting to imprisonment.

To achieve this, we have developed a network of community residences in partnership with third-sector organisations, which are responsible for supporting this process from semi-liberty to final release. This solution is vital for people who do not have the economic or family resources to access semi-liberty regimes. We currently have 80 places for people in this situation.

What progress has been made in the implementation of mediation and restorative justice practices in the field of Restorative Justice within the aforementioned Plan?

JP: Restorative Justice is one of the fundamental ways of addressing the rights and interests of victims. In this respect, we have developed two programmes almost from scratch. One has a specific focus on the ETA terrorist phenomenon in the Basque Country. Although this type of crime accounts for around 10% of the prison population in the region, it is a phenomenon of collective victimisation, so it was considered crucial to address the wounds and scars that remain in society, despite the fact that the terrorist organisation ETA has not existed for twelve years.

This programme has been designed with specific characteristics, both in its structure and in the selection of facilitators or mediators. They must be recognised by both victims and perpetrators in order to create an atmosphere of trust and facilitate the process. These efforts began at the end of 2022 and are being carried out in prisons, as well as with those convicted of crimes committed by the now-defunct terrorist organisation ETA who are in semi-liberty. The programme also includes work with the victims of the ETA terrorist phenomenon. We coordinate with the Vice-Ministry of Human Rights of the Basque Government.

In addition to the project focused on the ETA phenomenon, other restorative justice programmes are being developed for the rest of the prison population and other victims. A restorative justice pilot project for people serving community sentences has been developed in collaboration with a criminal court in Bilbao. This project starts with the offenders and later includes the victims.

What is your perspective on the measures implemented across the board by you and the Basque Government, especially with regard to ETA members convicted of terrorist acts, such as relocating them to their regions of origin and the progressions to semi-liberty regimes? How do you think these actions have impacted public opinion and perceptions within the justice system?

JP: First of all, I would like to stress that we have achieved something historic: all the people from the autonomous community of the Basque Country who were serving sentences in other regions for crimes related to ETA are now in our prisons.

For many years, these people were in prisons far from the autonomous community of the Basque Country, but we have tried to ensure that they now serve their sentences close to their places of origin, because we believe that this will improve their reintegration process.

Furthermore, we are convinced, based on expert opinion, that third-degree sentences (semi-liberty) are more conducive to reintegration, which is why we have also promoted the application of third-degree sentences for these people.

It is important to stress that we could not treat these people differently. Throughout this period, we have defended that the principle and the right to equality require that people from this organisation should be treated in the same way as other persons deprived of their liberty, with the nuances inherent in the penitentiary and penal legislation, which establishes specific rules.

Furthermore, we believe that restorative justice can be a more profound approach to this phenomenon, exploring the roots of the crime, taking responsibility and addressing the harm caused to the victims.

Throughout this period, I have made countless public appearances in the media and forums to explain our position.

We believe that all of these measures ultimately promote reconciliation between victims and perpetrators. These are ongoing processes that will require a lot of work and education over the coming years.

It is important to understand that a third-degree offender continues to serve a sentence and has restrictions and obligations imposed by the prison administration or the judge.

However, they also have the opportunity to achieve rehabilitation and reintegration in a more effective way. Moreover, this approach has a reparative effect for the victims, as third-degree offenders who work and earn an income have to use part of these funds to satisfy their civil liability towards the victims.

(...) we have achieved something historic: all the people from the autonomous community of the Basque Country who were serving sentences in other region.

Taking into account not only ETA prisoners, but also those convicted of terrorist crimes linked to other ideologies, how does the prison system deal with the challenges related to radicalism and violent extremism?

JP: Radicalism and violent extremism, especially Islamic terrorism, are indeed a challenge to the prison system.

Although we have not identified any excessive problem, we have internal measures in the prisons and we have established close coordination with other state security forces and bodies. We maintain cooperation with the Basque Autonomous Police, Guardia Civil and the National Police.

Vigilance and control are essential to prevent the spread of radicalisation and extremism in prisons. When we detect such signs, we work closely with the security forces to prevent and address the problem.

In addition, we monitor the selection of those providing religious support in prisons to ensure that there is no jihadist proselytising.

Vigilance and control are essential to prevent the spread of radicalisation and extremism in prisons. When we detect such signs, we work closely with the security forces to prevent and address the problem.

What is your vision for the future of the penitentiary system in the Basque Country?

JP: There are two fundamental challenges facing the penitentiary system. On the one hand, we have to deal with the issue of prison infrastructure. When we took over this responsibility, we inherited some very old prisons, built in 1948 and 1962, and the only more modern prison, built in 2011.

We also lack social rehabilitation centres and need to improve the existing infrastructure. To alleviate this situation, next year we will receive a new penitentiary centre, in Guipúzcoa, with a capacity for around five hundred people, and a social rehabilitation centre.

On the other hand, there is the question of staffing. We inherited a management system that was inadequate in terms of both the number and quality of staff. There has been an increase in the number of inmates who want to be transferred to our autonomous community, but we are faced with limitations in terms of staff and infrastructure.

It is crucial to reverse this situation and focus not only on security and control, but also on treatment and care. We need to bring in more professionals who are dedicated to providing treatment and support. We also need to encourage those who are dedicated to security to also strengthen their work in education and treatment.

In short, my vision for the future of the penitentiary system in the Basque Country is to deepen and improve the lines of action that have already been implemented and to face existing challenges. The aim is to improve the reintegration of prisoners and help them return to society, a challenge that requires the commitment of the whole of society and the institutions. Although the process will take time and we will face resistance, we are working in this direction.

Jaime Tapia

Advisor on penitentiary issues to the Basque Government

Jaime Tapia has been Advisor, with the rank of Deputy Minister, on penitentiary affairs for the Basque Government since March 2021. He has been a Magistrate for 33 years, specialising in juvenile and adult criminal justice. From 2012 to 2021, he was President of the Criminal Court of Appeal of Álava-Spain. In addition, since 2011, he has been Professor-Tutor of Criminal Law at the National Distance Learning University of Spain, where he teaches in the Law and Criminology degree courses. He has taught courses in Criminal Law at various institutions and organisations and has participated as a speaker in training activities related to victims of crime, especially minors and women.