Prison, terrorism and emergency are causing a vicious circle and a dangerous situation in Europe, which is no longer justified by the effective data emerging from risk analyses. Indeed, analysing the trends in a comprehensive view, maintaining an emergency situation could have serious negative consequences on the continent’s security in the coming years.

Emergency legislation on terrorism

Legislation on terrorism was born and developed in the context of emergency measures. The review process towards a “war on terror paradigm” began in 2001 with the attacks against the Twin Towers, in New York, USA, on 11 September 2001. It continued in 2004-2005 after the attacks in Spain on 11 March 2004 and in England on 7 July 2005. It further developed also in 2015 on the aftermath of the attacks in France on 7 and 9 January 2015 and 13 November 2015.

Finally, for now, that process has recently been consolidated with the European Union Directive 2017/541, which was formally adopted on 15 March 2017. As a result, several Member States have begun to update national legislation in line with Security Council Resolution 2178.

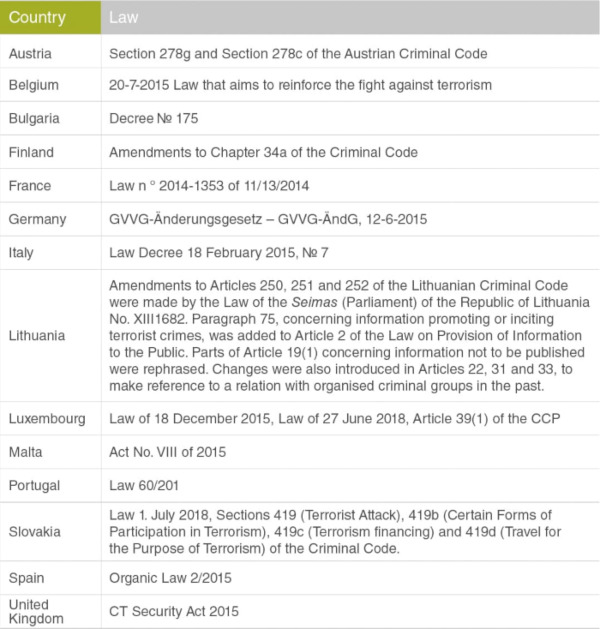

Table 1. Examples of counter-terrorism legislative changes taken by a few European countries

All of these emergency legislative reforms have one common element: they anticipate the threshold of criminal punishment in relation to the past, establishing new terrorism-related crimes (travelling for terrorist purposes, both abroad and in an EU country to commit terrorist crimes, joining a terrorist group or terrorist training groups, recruitment, receiving terrorist training, public incitement to commit terrorist offences or advocating terrorism – even online -, providing funds to commit terrorist acts or to contribute to terrorism, etc.).

Furthermore, these new laws criminalise preparatory terrorist acts as well as the intention to commit specific acts qualified as terrorism in the absence of “attempts and/or actions”. Finally, they extend jurisdiction beyond traditional national boundaries.

The abnormal trend

The legislative activism of emergency nature that is present in all European countries has caused a new phenomenon in the dynamics of European terrorism, with important repercussions in prisons.

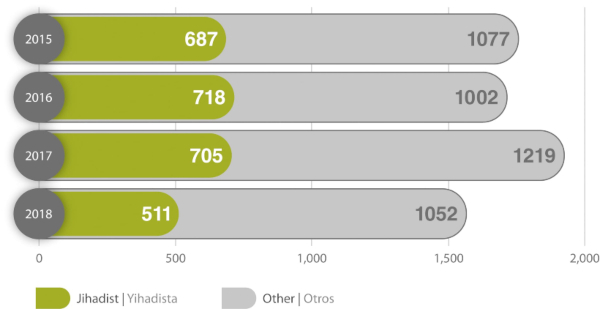

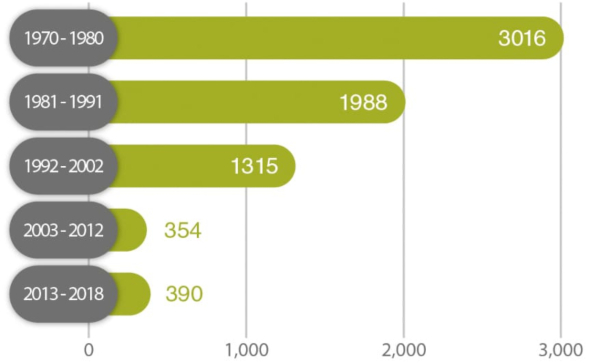

While, in reality, both the attacks and the number of their victims are decreasing, the figures for arrests, investigations and criminal convictions are increasing.

Graphic 1. Arrests in the EU for terrorism-related offences 2015-2018

Graphic 2. Number of deaths resulting from terrorist attacks, per clusters of years between 1970 and 2018

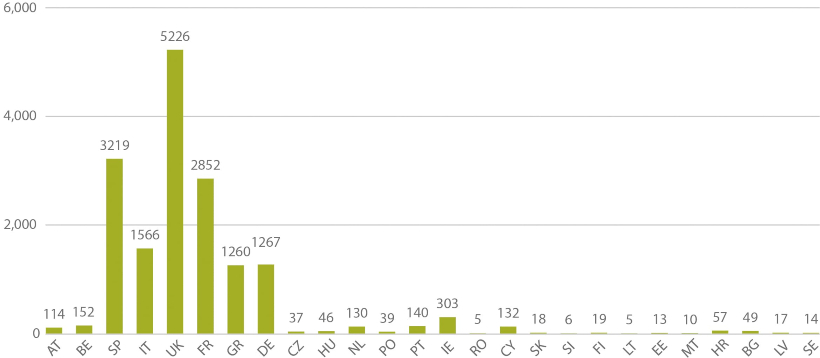

The result of this anomalous trend is especially noticeable within European prison systems, where several thousand prisoners are detained for crimes related to terrorism.

As highlighted by the EU-funded J-SAFE project led by the Triveneto Office of Prison Administration, Italy, such groups of prisoners include mostly young or very young offenders, including many minors, either already sentenced or awaiting trial. These individuals have a substantially different profile compared to the terrorists of the past.

The 3,016 people arrested for terrorism between 2014 and 2018, in Europe, are mostly young people whom in 96% of the cases did not commit bloody attacks or acts but were faced with the new rules for preparatory terrorist acts, internet activities or support to travels to Syria and Iraq.

However, entering a prison for having been sentenced for a terrorism-related crime – hence, having “a terrorist title” – has serious implications in the detention regime and security circuits to which the prisoner is subject. In fact, it means ‘hard’ prison regimes, according to the model of Article 4bis of the Italian prison regulation, or in high-security circuits, which seriously hinder or limit rehabilitation, including contact with the families, phone calls and all forms of resocialisation.

In short, for those people detained for crimes related to terrorism, treatment is suspended, or they are provided forms of compulsory re-education that somehow resemble the worst prison regimes of the past.

Finally, these are paths with a strong ethnical-religious characterisation that mainly concern non-European third-country citizens, to whom, at the end of their prison term, administrative security measures are applied, meaning forced deportations to countries where prison systems are not always in accordance with international standards.

Paradoxically, many thousands of youths with European passports who are currently imprisoned in these harsh conditions with very severe de-socialisation effects, will be released within the next two years, since convictions for new types of terror-related crimes without specific bloody acts are now milder than in the past, ranging from 4 to 6 years on average.

For those who are aware of what is happening, it is very clear that this situation does not favour the European security system by letting thousands of young people be completely abandoned by their families and their communities of origin, who fear the stigma of terrorism and police controls. In addition, these young prisoners feel they are victims of a system and are guilty of a crime they often do not understand.

Graphic 3. Number of terrorist attacks per country occurred between 1970 and 2018

Moreover, for those immigrants in detention and with the prospect of being deported to their home countries, the temptation to commit parasitic crimes while in prison to avoid deportation is very high. This may explain the many violent acts perpetrated by those kinds of prisoners in recent years, thereby both undermining prison safety and endangering the lives of prison staff.

Restorative justice as an alternative

The development of innovative strategies and solutions that aim to reduce recidivism and radical behaviours is at the core of several European Recommendations, Decisions and Directives, which focus on the positive effects of alternative penal measures compared to imprisonment sentences.

As referred to in the Antiterrorism Directive, the solution is framed from a restorative justice point of view that aims at resolving or bringing down the conflict and creating a safer society.

Some of the indications with European and transnational impact include:

– Recommendation concerning the Position of the victims in the field of criminal law and criminal procedure (Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe – Collection No. R (85) 11 of 28 / 06/1985);

– Resolution on the Development and Implementation of Mediation and Restorative Justice Interventions in the field of Criminal Justice (United Nations Economic and Social Council No. 1999/26 dated 28/07/1999);

– Recommendation concerning Mediation in Criminal Matters (Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe No. R (99) 19 adopted on 09/15/1999);

– Vienna Declaration on Crime and Justice (X Congress of the United Nations on the Prevention of Crime and the Treatment of Inmates – Vienna 10-17 April, 2000);

– Resolution on the Vienna Declaration on Crime and Justice: New Challenges in the 21st Century (United Nations General Assembly – No. 55/59 of 04/12/2000);

– Framework Decision of the Council of the European Union concerning the position of the victim in criminal proceedings (2001/220 / JHA of 15 March, 2001) replaced by the Directive2012/29/ EU of 25 October, 2012.

The possibility of resorting to restorative justice for inmates under terror-related legislations varies in relation to the crimes and conditions under which a case can be managed, according to the legislation of each Member State. Despite the diversity of existing forms of restorative justice, they all share two main characteristics: the voluntariness to participate in a reparative activity, and the need for the path and the activity to be guided by third parties, which are impartial and specifically trained for this type of intervention.

The main forms of restorative justice include: 1) extended mediation meetings that tend to create a dialogue with parental groups and/or all groups involved in the commission of a crime (Community / Family Group Conferencing); 2) the performance of work activities in favour of the victim (Personal Service to Victim) or in favour of the community (Community Service); 3) mediation between the offender and the victim (Victim-Offender Mediation) and 4) meetings between victims and the offenders who have committed similar acts to those they were victims of (Victim / Community Impact Panel).

So, in view of all this, the message to the political decision-makers is clear: the emergency phase has passed; prison shouldn’t be the collector of socio-political conflicts, and in fact, beyond a certain limit, it risks strengthening them. It is time to return to common policies also in the field of terrorism and the rule of law.

//

Sergio Bianchi has an academic background in Middle East studies, with 20 years of experience in intelligence and security. He works in cooperation with security, academic and media agencies and is a certified CEPOL trainer. Since 2015, he has been a consultant in the areas of security, counterterrorism and also an Inter-force trainer in the Triveneto regional branch of the Italian Ministry of Justice, where he established the prison forensic laboratory. He is also the Director of the International Department in the Swiss section of the Agenfor International Foundation.

Advertisement