Interview

Dan Halchin

PhD., Director-general of the Romanian Penitentiary Administration

Overcrowding remains a problem in Romanian prisons. The most recent report from the Council of Europe’s Committee for the Prevention of Torture identified a few areas where there is room for reform. These include improving living conditions, offering purposeful activities to help prisoners prepare for social reintegration, increasing numbers of prison staff and ensuring adequate healthcare services.

In this interview, Director-general Halchin reveals the strategy to face the challenges and talks about the progress made. There is a solid commitment to reform and modernisation of the prison system, which would be a difficult path without external cooperation, especially from Norway.

What have been your priorities when tackling the challenges facing the prison system? And what progress and developments would you highlight so far?

DH: I’m keenly aware of existing challenges in our prison system. Although many concerns can, and should, be tackled, our priority has been improving and extending the physical infrastructure. It’s hard to positively influence and rehabilitate inmates when you have poor, old or inadequate penitentiary facilities.

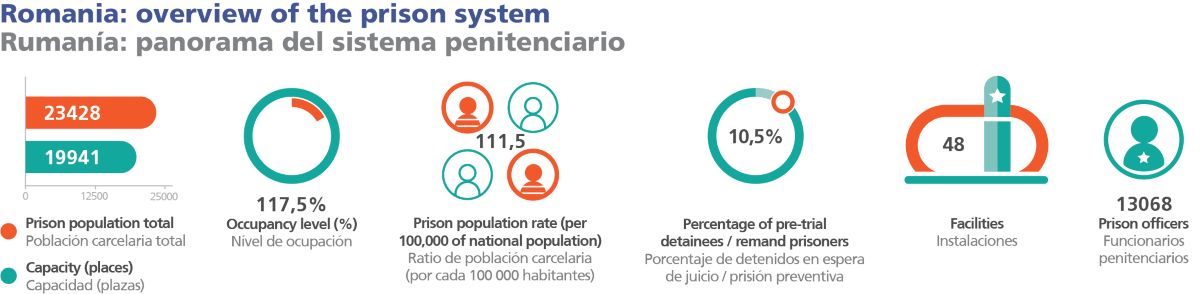

In 2020, the Romanian Government issued a National Memorandum to address this issue. In summary, by the end of 2025, many of the current prisons will have extended their capacity and two new prisons will have been built. We’re adding nearly 8,000 new detention places to the existing capacity, which is currently adequate for close to twenty thousand inmates.

So far, the five-year roadmap for these extensions is progressing as planned. For 2021, we had projected increasing the capacity by 210 new places and we managed to surpass this. This year (2022), we’re on track to add 445 new beds. With the extensions and new prison facilities, we’ll increase capacity by 1,275 places in 2023, another 5,419 beds in 2024 and 500 in 2025.

We have made significant progress in creating a rehabilitative architecture and our recidivism rates strongly reflect this.

We have witnessed a steady decline in recidivism with the rate decreasing from 43% in 2010, to 37% in 2021. We offer educational, psychological and social assistance programmes based on the inmates’ individual needs. We rely on a multidisciplinary evaluation process to design each inmate’s Individualised Intervention Plan.

Prison programmes in education, training and citizenship span schooling, vocational training, information and culture, religious and moral workshops, hobbies and occupational activities, sports and recreational competitions and meetings, as well as cultural/art events.

We also offer psychological counselling, psychotherapy, suicide risk prevention and programmes targeted at inmates with mental disorders, drug addictions, aggressive behaviour, etc., as well as a programme for inmates with convictions for sexual offences.

Social assistance programmes are a key focus, particularly in terms of family education and strengthening of relationships between inmates and their support networks, domestic violence prevention, social mediation and individualised social work, amongst others.

Romania introduced a legal provision with specific amendments addressing pretrial detention. After this bill, there was a drop in pretrial detainees from 3,753 to 3,037. (…) New preventive measures resulted in a decrease in the number of remanded inmates by nearly 50%.

JT: Excessive pretrial detention is widespread across Europe and elsewhere. However, Romania has a very low percentage of untried detainees compared to the European average.

Which measures have been/are being considered to support alternatives to incarceration and reduce pretrial detention? What role does the prison administration play in the design of such policies?

DH: On the prison side, we’ve constantly highlighted that excessive pretrial detention has a negative impact, mainly by causing overcrowding. Furthermore, given the uncertainty related to this category of detainees, rehabilitation and sentence execution planning are put on hold.

In 2003, when our total prison population exceeded 48,000 inmates, Romania introduced a legal provision with specific amendments addressing pretrial detention. After this bill, there was a drop in pretrial detainees from 3,753 to 3,037.

Following entry into force of the New Criminal Code and New Code of Criminal Procedure on 1st February 2014, the new preventive measures that were adopted resulted in a decrease in the number of remanded inmates by nearly 50%.

This feat has been achieved through the courts progressively applying more alternative non-custodial measures, such as judicial control and house arrest. Currently, we have around 2,400 individuals remanded in custody. In 2020, the Romanian Parliament adopted a new bill that provides a legal basis and guidelines to implement the electronic monitoring of offenders as an alternative measure to imprisonment.

We are currently working on implementing this project in cooperation with the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the Probation Directorate and the Government Communication Service. We are confident that once this system is in place, the number of pretrial inmates will drop even further.

What else can you tell us about the electronic monitoring uptake in Romania?

DH: According to Romanian legislation, electronic monitoring systems can be used by the Police and the National Penitentiary Administration to enforce measures such as judicial control, judicial control on bail, house arrest or restraining orders. They can also be used to remotely monitor inmates with pretrial/community orders.

The prison system may resort to electronic monitoring to increase security, both within the scope of rehabilitation and reintegration-related activities and for surveilling inmates on permitted leave.

We consider that electronic monitoring can be useful for all categories of inmates when they are outside their place of detention, for instance, for work activities outside the prison premises.

From a system-wide average of 3,300 inmates in open prisons, it is estimated that 300 working inmates will be subject to electronic monitoring. I see electronic monitoring as a security enhancement in certain situations and places.

Other advantages include increased inmate involvement in work activities and the judicious use of staff, thus reducing costs and optimising human resources.

Electronic monitoring can have a significant impact on the remand population, too. Of the current 2,400 pretrial detainees, up to 480 could receive a community or restraining order with electronic monitoring.

In 2020, the Romanian Parliament adopted a new bill that provides a legal basis and guidelines to implement the electronic monitoring of offenders. Electronic monitoring can have a significant impact on the remand population, too.

What are the Romanian prison system’s priorities concerning digital modernisation? What innovations are most needed to improve the agency’s goals?

DH: The daily interaction between inmates and the prison administration is still done using pen and paper. This system has limited reliability and creates a heavy bureaucratic load.

We are currently exploring a robust Document Management Software that would allow sustained cooperation between the headquarters and prison units. We are confident that we will manage 99% of the documents in a centralised electronic environment by the end of 2024.

In addition, through a European Union-funded project, we are developing new software to manage the prisoners’ records. The cost of this investment is nearly €1.2 million.

Finally, we are studying the possibility of providing large-scale access to audiobooks across the prison system. This is expected to have considerable impact on the inmates’ rehabilitation, especially by tackling illiteracy (more than 6% of the prison population is illiterate) and other vulnerabilities.

JT: Different multilateral organisations and programmes support the modernisation of the Romanian prison system.

Can you explain the importance of such cooperation agreements, namely the one with Norway, through Norwegian Grants?

DH: We are seeking to reinforce our current relationships with various prison and probation systems in many countries. In this context, the bilateral relationship between Romania and Norway has particular relevance. Since 2014, we have built a strong relationship with the Norwegian Prison and Probation Service. This fruitful exchange of best practices came about through several projects funded by the Norwegian Financial Mechanism (NFM) 2009-2014, in close cooperation with partners from the country’s prison service.

We are currently implementing four projects funded through the NFM 2014- 2021, capitalising on the excellent relationship we had already established.

The overall funding of current projects through Norwegian grants amounts to nearly €43 million. Most of the funding (€31 million) is being used to finance the Correctional Project.

The Correctional Project aims to improve Romanian prison and probation capacity and provide reintegration services to offenders (prison inmates, ex-convicts or those serving sentences in the community). This initiative’s primary strategy consists of implementing the Norwegian “seamless” principle and investing in the development of human capital.

The “seamless” concept seeks structured and enhanced cooperation between prison and probation, which are two different systems in Romania. In addition, the project is working to enhance cooperation with local authorities to ensure an integrated approach to specific interventions for offenders and a smooth transition from prison to the community.

Besides creating new detention places, this project provides for several pilot correctional centres. This is a first for Romania, as the new facilities will set the stage for re-thinking the dynamics of the relationship between the prison system and the probation service.

Another critical improvement introduced by this initiative is the modernisation of the National Training School for Prison Officers. The project started at the end of August 2019 and is expected to be complete by April 2024.

I am pleased that several important project milestones have already been achieved. We have completed the first evaluation of the social reintegration instruments, the awareness of intercultural diversity of offenders and the evaluation of the organisation’s internal and external communications. We have also provided training for our prison officers on communication topics.

We have managed to complete the design phase (including the feasibility study and the technical design documentation) in most of the pilot correctional centres and we will soon launch the public tender for the construction phase.

We have worked hard to progress the project’s activities, but also to initiate new ones, such as the first organisational assessment of the prison system, developing the general work methodology so as to apply the “seamless” principle. Finally, we have provided training for many of our prison officers on various topics.

4NORM(-ality) is another project supported by the EEA and Norway Grants, budgeted at €5 million. The project aims to improve the social reintegration of convicts serving their sentences in three of our prisons. Project goals include staff training, a new research unit within the prison administration, and strengthening the existing research department at the Probation Directorate.

In addition, this project also seeks to improve detention and working conditions for inmates, set up an activity office at one prison, provide training for prisoners according to current job market demands and develop an accountability programme for inmates based on recommendations from the Council of Europe.

The 4NORM(-ality) project also explicitly addresses the issues of inclusion and empowerment for Roma offenders and the social inclusion of other vulnerable groups of inmates. The accountability programme, prison officer training and other post-release reintegration measures contribute to those goals. This project has a particular emphasis on gender equality, anti-discrimination, transparency and anti-corruption, as these are all cross-cutting issues.

The accountability programme has been developed with the support of Norwegian experts. Its main objective is to adequately prepare inmates for release from prison and to achieve smoother social reintegration. The end goal is to reduce recidivism. At the same time, we have trained prison officers on the normality principle. The programme is being tested with more than 100 inmates in three prisons.

The National Penitentiary Administration is also responsible for the SECURE project – “Safe and Educated Community Undertaking Responsible Engagement” (A safe, educated and responsibly involved community). This project will analyse the causes of reoffending and support public policies to reduce recidivism in Romania. In this endeavour, we are working with the Crime Prevention Directorate of the Ministry of Justice. The initiative involves a multidisciplinary programme for violent and drug-addicted offenders, aiming at developing their prosocial skills. The goal is to facilitate their progression through the system all the way to full social reintegration.

This project includes a new multifunctional pavilion at Mărgineni Prison, which will have spaces dedicated to increasing detainees’ responsibility and autonomy and delivering rehabilitation and reintegration initiatives.

Finally, we are also promoting the CHILD – Child Inclusion Learning and Development project in partnership with the Târgu Ocna Educational Centre and City Council.

With a budget of around €1.5 million, we are promoting the social reintegration of minors and adolescents through the improvement of educational activities and specific assistance provided by the Târgu Ocna Educational Centre. This initiative will also remodel and endow two accommodation wings, medical facilities, workshops and spaces for activities. In addition, we will put in place vocational training and a multisensory stimulation programme for children in our care who have ADHD and learning issues.

We are also investing in working standards for psychiatric care and procedures for managing violent and aggressive behaviour. The initiative includes staff training and building and equipping a visitors’ area for families, where they will be able to benefit from counselling.

We trust that the projects funded by the Norwegian Grants will contribute to transforming Romanian offenders from “socially assisted people” into responsible citizens who are diligent employees, attentive parents and good neighbours.

Starting your role as Director-General during the COVID-19 pandemic, what added challenges did the prisons have to manage?

DH: I faced the COVID-19 pandemic both as a Prison Governor and as Director-General. It was quite a challenging period for me in both positions, as nobody had a roadmap or checklist for dealing with such a terrible situation.

However, with careful planning, tremendous understanding and dedication from inmates and staff, we sailed through the challenges relatively calmly. Fortunately, we didn’t experience any riots, large numbers of infections or fatalities during the pandemic.

We developed a detailed master plan covering every aspect of prison activity and inmates’ rights. We sought to prevent the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus within prisons through social distancing, intensifying sanitisation and providing protective facial masks to inmates. Other measures included limiting and controlling external contacts, wherein we reduced the number of working stations and put up acrylic separation panels in the visiting rooms.

Participation in programme activities was in small groups, according to the imposed restrictions, and we limited inmate transfers between prison units. In order to ensure the maximum possible educational provision, we implemented remote training. It was only during the State of Emergency, that was in force for two months at the beginning of the pandemic, that we had to restrict visits and stop permissions. We resumed those as soon as the national authorities lifted the State of Emergency.

In general, we did not suspended visitation in our prisons. Visits were only delayed in the case of inmates who tested positive for COVID-19, so as to observe mandatory quarantines.

To maintain connections with support networks, we increased daily phone call limits to 45 minutes for convicts in maximum-security prisons. Prisoners in other centres were allowed daily calls of up to 75 minutes. We streamlined online calls relative to the number of visits to which each inmate was entitled. In addition, we took advantage of virtual communications for court hearings.

Subsequently, during the State of Alert, we continued granting online communications to inmates, according to the provisions adopted by Law No. 55/2020 on Measures to prevent and counter the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Online communications increased by around 22% in 2021 compared to 2020.

New national legislation included provisions that benefited the prison services and these are still in force. The outstanding efforts of prison staff in explaining the mandatory restrictions and the importance of vaccination is also worth mentioning. Thanks to their exemplary work, our prison vaccination rates exceeded 80%, twice the percentage reached outside the prison walls.

Dan Halchin

PhD., Director-general of the Romanian Penitentiary Administration

Commissioner Dan Halchin (PhD) is a senior career prison officer with more than 20 years of experience. He has served two terms as Prison Governor (2006-2010 and 2017-2021) and held the position of Deputy Director-General between 2015-2017.

His experience has been a valuable asset to two international missions in Kosovo and Libya, for six and nine months, respectively. He was sworn in as Director-General of the Romanian Penitentiary Administration in April 2021 for a second four-year term. He oversees 34 prisons, 6 prison hospitals, 4 educational centres and several support units, managing 23,000 inmates and more than 13,000 prison officers.