// Interview: Priit Kama

Deputy Secretary-General for Prisons, Estonia

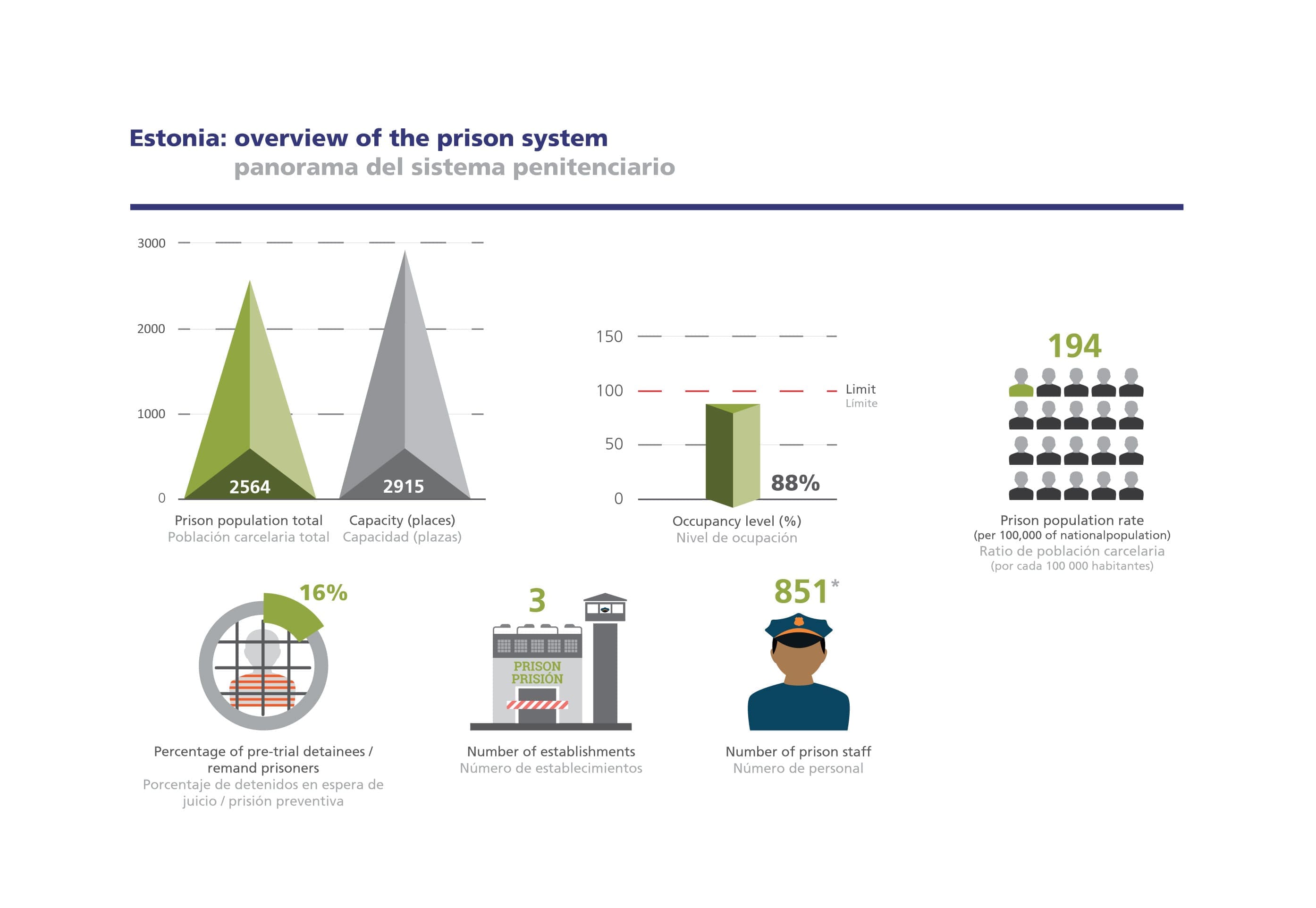

JT: Although Estonia has a high prison population rate per 100 000 inhabitants, the system works well in terms of physical capacity, and it has been witnessing a decrease of the prison population over the years, since the 1990s (Source: PrisonStudies.org), plus, there has been a process of modernisation.

Can you please explain the process of modernisation of the Estonian correctional system and what have been the main changes?

PK: Although the present figures of prison population in Estonia are quite high, they used to be much higher, twelve years ago.

When I took office, in December 2005, the number of inmates was approximately 4500 altogether, whilst nowadays there’s just over 2600 inmates.

Such decrease is due to legislation reform, especially concerning conditional release; it means that if half or two-thirds of a prison sentence is served, the case will automatically go to court, which can be decided for a conditional release.

Besides that, we have built new prisons and actually, today, we have three institutions, each one housing 800 to 900 inmates. Our infrastructure is quite recent: one was built in 2002, another one in 2008, and a new prison will be completed in the country’s capital, Tallinn.

At the moment Tallinn’s prison is the only old prison, but that is going to change as a new one is going to be inaugurated, in December 2018. So, by then, all of our establishments will be very recent.

Another reform that the prison system has undergone concerns the personnel. We have introduced new educational requirements and physical assessments, which has been very important for Estonia.

Presently, all prison officers are proficient Estonian speakers; the new minimum requirements are set to a language level of C1.

In the beginnings of the 90s, there was a transition period – let’s not forget that Estonia was under Soviet Union’s occupation.

By then, the prison service was quite underfinanced, it employed many Russian speakers who were not even able to read the Estonian legislation, and, of course, it was a real problem, having staff that was not able to work in compliance with the requirements of the Rule of Law, nor of delivering the service that they were supposed to. At that time there were seven prisons, which ran in old buildings.

During the Soviet occupation, in the prison service, there was only a very theoretical idea of social rehabilitation. It was mostly understood as a repressive institution. This mentality has changed a lot, of course.

And there have been efforts to restore the Estonian prison service tradition that dates back to the 20s and 30s, when Estonia was independent. Part of that tradition is sports. Before the Soviet occupation, sports used to be very popular in the prison service and several Estonian prison officers were Olympic medalists, for example Kristjan Palusalu (Olympic gold in both Greco-Roman and freestyle heavy weight wrestling).

The Estonian prison service has been re-establishing this positive identity that it held 90-100 years ago. We don’t consider ourselves to be the successors of the Soviet prison system.

In the beginnings of the 90s the system was quite underfinanced and it employed many Russian speakers who were not even able to read the Estonian legislation.

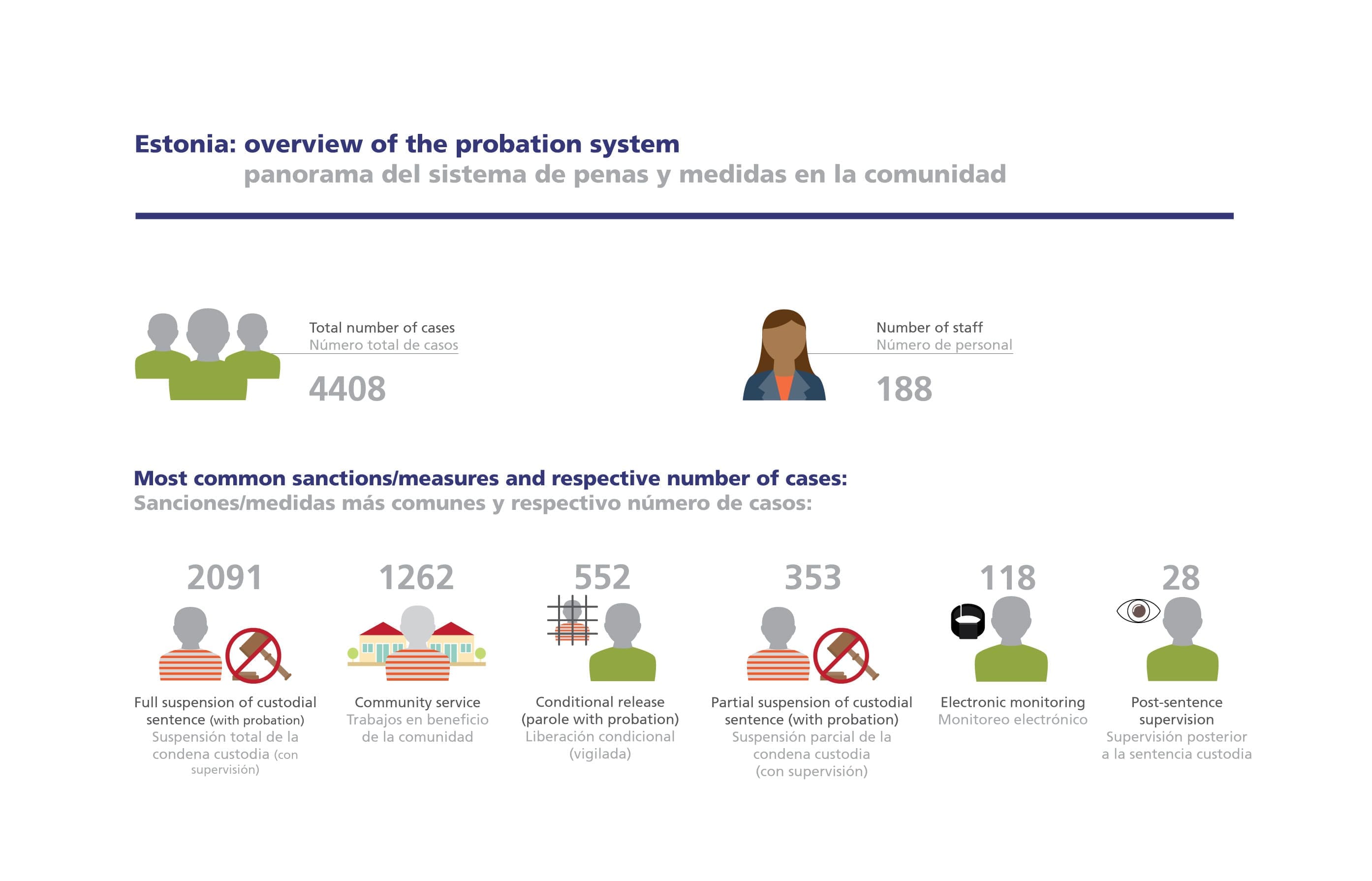

JT: And in the probation service, have there been many changes as well?

PK: Estonia used to have probation also in the 20s and 30s. At that time, it was mostly organised by NGOs, but the service hasn’t been re-established until the end of the 90’s and, when it was restored, it was set as a structure divided into departments which were dependent on the courts.

Then, ten years ago, there was a reform and the system was transferred from the courts’ system to the prison service and, in our case, to each one of the regional prisons. Hence, each prison governor also has responsibility for a probation office inside prison facilities.

Regarding the transfer of staff members from prison duties to probation ones, it is quite flexible, which, in practice, means that some prison officers stay responsible for the same offenders both when they’re detained serving their sentences in prison, and when they’re on probation, outside prison.

JT: To what extent the fact that you have almost 40% of foreign nationals in prison is a challenge to the system, and how do you address this problem?

PK: The large number of foreign nationals in Estonian prisons is also connected with our Soviet past: many are actually Russian speakers, with unspecified citizenship, which means that some might be entitled to Russian citizenship, but officially they haven’t applied for it or they don’t have documents.

The most common citizenship among foreign prisoners in our establishments is the Russian, followed by Latvian and Lithuanian.

A large number of the ones who have unspecified citizenship will probably remain in Estonia, so we try to integrate them; for that purpose, we have large programmes for teaching Estonian language in prison – that is one of our specific features, because it’s quite complicated to work on the integration of offenders who don’t know the national language, as they’ll have limited possibilities in the labour market and also a limited understanding of what takes place in our society.

Fortunately, we have several hundreds of inmates who are studying Estonian. I believe this is a positive difference compared to some other countries.

In addition, we have tried to integrate those language programmes with Estonia’s general knowledge and culture – inmates simultaneously learn the language and are able to develop skills in topics such as labour market, how to find a job, how to go to the labour office or some other very important things that are good to understand and know if you live in Estonia.

To conclude, I can say that such a high percentage of foreign nationals is quite a big challenge. One thing that surely is helping us tackle this issue is the fact that our older generation of prison officers are able to communicate, in Russian, with the majority of our foreign inmates.

The correctional system has been re-establishing the positive identity it used to have. We don’t consider ourselves to be the successors of the Soviet system.

JT: What are the main international cooperation projects that the Estonian correctional system has been/is involved in, and what are the benefits?

PK: We have had different partners. We have a very practical cooperation with Latvia and Lithuania; I’ve just recently met my colleague from the Lithuanian prison system. We often “share the same prisoners” with these two countries, since we have a lot of transfers. Simply, because of our history, we can say we are good friends and we have a lot of practical cooperation.

Culturally, Finland is also an important partner of ours, regarding the correctional system – Scandinavians have prison services that we look up to – they’re a good example of what ours could be in the future.

From Scandinavia, we have learned many topics concerning social programmes, namely on how to find different activities for prisoners, on how to organise resources for prison work, as well as practical management questions.

Furthermore, specifically from Norway, we have tried to learn how to manage smaller units, since each one of our three large prisons includes six different units, which are managed by unit managers who take over a lot of the work that in other systems is usually performed by the governors.

Also, concerning legal matters – namely, our prison law has been elaborated according to the German example – we are historically connected with the German tradition, so, in that sense, we have cooperation links with some German states, like Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, for instance.

The UK has been a good partner especially because they have relatively large prisons, and that means that some of their challenges are similar to ours. Similarly, our cooperation with Northern Ireland has also been fruitful concerning emergency plans and management, given that the common characteristic is large prisons.

There are some very practical aspects that can be better addressed if we have partners that can help; for example, we have recently introduced (October 1st, 2017) a complete smoking ban, and right now the UK is doing it – they can draw from our example. The other way around: from England and Wales (UK) we “have brought” risk assessment systems and different ideas for emergency management.

JT: What are the main goals of Estonia’s prison and probation system at this point and what challenges do you see coming in the future?

PK: Presently, our main concern and task is the reduction of recidivism.

As far as practical matters are concerned, I truly believe that we have to give more responsibility both to middle management and to the lower management level.

Prison and probation management in Estonia is a rather complicated issue, and I hope that in the future we are able to let more decisions be taken by the lower levels of management, that is, to reform the hierarchical structure that we still have nowadays.

It’s also true that, in general terms, our system needs professionals who are more educated – although we have a relatively good situation if we compare it to ten years ago – we still have some needs regarding the educational level of both our prison officers and other employees in the system.

JT: The 23rd Council of Europe Conference of Directors of Prison and Probation Services will be hosted by Estonia, in June 2018. This event also marks the Annual General Meeting of EuroPris, the European Organisation of Prison and Correctional Services.

What is the significance of these events for Estonia’s correctional system?

PK: It’s a regular duty of each prison system in Europe and we have had prior good experiences with conferences.

This conference is very good for networking and exchanging ideas with colleagues from all over Europe and ultimately from all the member states of the Council of Europe, therefore I’m hoping to establish agreements and partnerships with several Directors General.

Hence, for me and for my colleagues, it’s very practical to see all of our homologous in an event that will be the stage for talking and sharing experiences.

I believe this upcoming conference is beneficial to the Estonian correctional system, and it will be an opportunity for us to reciprocate all the contacts, the useful knowledge, and study visits that the different member countries of the Council of Europe and EuroPris have given us during the last decade.

//

Priit Kama is carrying out his second term as Deputy Secretary-General for Prisons. He has been serving in the Estonian public service since 1993, and he has been in the corrections’ field since 2005. Prior to this date, he had been Deputy Secretary-General of the Ministry of Justice, between 2003 and 2005. He is a graduate from the Faculty of Law of the University of Tartu, and holds a master’s degree in Economics from the Tallinn University of Technology.

Advertisement