// Interview: Annie Devos

Director General of the Houses of Justice, Wallonia-Brussels Federation, Belgium

JT: A document published by the Confederation of European Probation, in 2015, reported that the European Probation Rules were not mentioned in any Belgian policy nor practice document and that the field staff might not be aware of the existence of such rules.

What are your comments on this?

AD: In fact, I wrote that. However, it is no longer completely correct. At the moment we have another structure where we work with the recommendations of the Council of Europe.

Being a member of the working group of the Council for Penological Cooperation (PC-CP) of the Council of Europe makes the recommendations more and more tangible. However, in practice, many countries use the recommendations but aren’t really explicit about them.

So, I think there’s quite a lot to do when it comes to increasing the knowledge of those rules, to popularise them as a framework for all practitioners in Europe. We are working on that and trying to improve.

JT: How does the Belgian probation system work?

AD: We work with people who are in conflict with the penal law, applying court orders. Thus, we work primarily with people living in Belgium. In addition, for the framework decisions, we sometimes work with colleagues from foreign countries on a more structural level.

A way to enrich the exchange of practice and the discovery of how peer services work is through the meetings of the Confederation of European Probation (CEP). For instance, we can share our experiences about the work that we do with the victims, which is completely different compared to other countries.

In Belgium, the “victim support services” are an integral part of our probation services. I consider this as very enriching for an organisation because you see things differently, we have access to an overall picture of the reality, which, in turn, makes the work with the victims more efficient. On the other hand, if we have a better view of the victim’s personal experience and their possible difficulties, there’s a beneficial effect on the offender.

JT: So, in this sense, are you talking about any restorative justice efforts – bringing the victim and the offender together and working that aspect – or just keeping the victim informed of the measures that the offender is undergoing?

AD: In fact, regarding that aspect of our work, we have three services: firstly, we provide information and keep the victims aware of the sanctions and/or measures imposed to the offenders; secondly, we organise the process of mediation whose responsibility falls under both the magistrate and the probation officer – this is a process which necessarily yields effects on the penal process.

Thirdly and finally, we collaborate with non-for-profit organisations: the probation services give them grants to proceed with real restorative justice work. In this case, the penal procedure may or may not be impacted.

JT: Are there any singularities that you’d like to highlight between the Belgian probation system and other systems in Europe?

AD: In practice, we have existed for almost 20 years. The decision to create this service was taken in the late ’90s, after a horrible murder case; as it often happens in the justice area, a big change is triggered by a very difficult situation!

As an organisation, we have evolved tremendously but we have always tried to put the human being – the offender or the victim – at the centre of our intervention. We use the methodology of social work, meaning that we really praise the respect for human rights and also act according to the recommendations of the Council of Europe.

Plus, we also manage electronic monitoring. In this field, it is particularly important to put the person at the centre of the intervention. The attention can be completely riveted and overwhelmed by the abundance of technology, but in fact, you always have to bear in mind what the end and the means are. Electronic monitoring is a means rather an end in itself and we really try to reflect it.

Belgium has many alternatives to detention, but it also has a high number of inmates in comparison to most of the western European countries. If we look at the figures for Scandinavian countries, for example, their imprisonment rates are much lower.

Probation, October 2016

JT: The advent of crucial reforms in the Belgian justice system since the mid-1990s has resulted in the categorisation of various types of professionals as “justice assistants”.

Who are these justice assistants, and what role do they play in the Belgian correctional system?

AD: They are probation officers. It is very important for them to have a very clear professional position. They work in collaboration with both magistrates or prison governors because orders may be sent by both authorities.

Our justice assistants are bound by five driving principles that are really crucial when carrying out their work with offenders and victims.

One is “Empowerment”: making offenders and victims more emancipated, more citizen-like, accountable for their own decisions.

Another word is “Responsibilisation” – people we work with are urged to take part in the decision-making and to move forward with that decision. The third orientating principle is the “Non-Standardisation” meaning that both probationers and victims have their own values, so, the justice assistants have to act like a co-operative part that assists them in moving ahead within a given framework of values.

This is a big deal in our work! We often serve as change managers, and it is always difficult to change. What we are asking offenders is particularly difficult because it has to do with their way of life. This is really demanding and challenging.

Another principle is “Non-Substitution”: it means that we are not doing anything in place of the people; we try to get them moving and make them aware of the situation and to encompass their evolution step by step… In this regard, our method is to make proposals and requests to the probationers we are working with; we always try to start our questions with “Is it possible for you to…?” These little things can really have a big impact!

And, the last but not the least principle is “Damage Control”. This means that when we think that a given situation or condition is no longer efficient, or does not make sense to the offender or victim anymore, we try to work upon it by giving this feedback to the judge or prison governor.

Our five driving principles: Empowerment,” Responsibilisation, Non-Standardisation, Non-Substitution and Damage Control.

JT: To what extent do you think that the probation system in Belgium is well understood within the criminal justice system, compared to other bodies, such as the police, the prison service and the courts?

AD: Frankly, when I was a prison governor, everybody knew what my role was… When you are working in the probation sector, you may get questions like: “What do you actually do? What does it mean?”

When a probation officer works with offenders on things such as getting up every morning, or how to settle the victims’ compensation, it is not visible! Instead, we get seen only when failures arise or when people really need us.

I see that the profile of police officers, judges or prison governors is crystal-clear, whereas ours is not that obvious due to the wide variety of interventions we carry out. I recognise the need for promoting our sector, that’s why we’re working on a communication plan at the moment.

We have been making a lot of effort to get awareness from the judicial authorities. But, really, my question is about the collaboration in the penal system. If you look at the overall picture, we are at the end of the “penal chain”.

We may regret that the means are mainly and massively directed to the prosecution: outside sentence enforcement courts, the probation and the sentence execution sector are underinvested. I think that we need not only to make big efforts in terms of communication, but also to emphasize that we work for a mutual broader goal which is mainly the public safety.

Nowadays, the probation area is increasingly known due to the phenomenon of radicalisation. Terrorist attacks have been terrible events that led to an increase of the collaboration with the judicial system, however, such collaboration is still under construction and is being done step by step.

JT: Your Directorate-General (DG) was created in October 2005, rooted in traditional social work method. However, with the de-federalisation, a competences’ transfer took place from the federal level to the three different language communities.

How does the system survive successive reforms and modifications, and to what extent does it remain true to the original purpose of social work?

AD: At first, we were a part of the judicial organisation, then, for three years, we were under the prison administration, and afterwards, we have become a self-managed directorate-general within the federal Ministry of Justice. Again, in 2015, the sixth state reform split the DG into three organisations on the basis of the linguistic communities.

These changes have resulted from political decisions. For the organisation, it takes a lot of energy to make it work. On paper, everything seems to be fine, but once you are immersed in the reality, it is not that seamless.

To me, reforms and changes have reinforced our purpose of judicial social work because we really had to be more than aware of our professional position. We constantly have to remember who we are, what we are doing, what is our scope, how we work, and legitimate why and for whom we are here.

At my level of responsibility, the organisational aspect is very heavy, but I think that the message is clearer than ever for my staff: it is social work and the five principles I mentioned.

Reforms and changes have reinforced our purpose of judicial social work.

JT: What are your main concerns and objectives at this point?

AD: I would like to be in a more stable situation at the political level because, at this moment, more than 40% of my time is spent on operations, given our complex structure.

Regarding our job itself, I think that we need to do more in relation to the Framework Decisions so that we can contribute even more to a better society for the European citizens.

Additionally, in my opinion, if we go ahead with alternatives to detention, they should be real alternatives. Presently, I would like to see the concept of desistance implemented in a more practical way; for such, we’ll be giving grants to NGOs so they work on that field with the aim of giving more chances to the offenders we follow.

Often, judges refer probationers to psychological treatment but people have problems with basic and concrete things like subsistence, housing, etc. More needs to be done in this regard, and it is possible to do so. Our partners and collaboration are very important.

I hope that terrorism and radicalism will be limited, with our help. The people we are following for being linked to radicalism or terrorism represent a small number amongst all the probationers, but they require an incredible amount of work and time.

Our role is not always easy because intelligence and security services tend to be increasingly interested in our practices, however, probation practitioners have to work in a certain frame, with plenty of transparency both with the magistrates and with the offenders.

More needs to be done in relation to the Framework Decisions.

JT: What are your expectations with regard to the area of probation in Belgium?

AD: I am always optimistic, we are in a growing and diverse reality.

Since 2014, in Belgium, there is a new possibility: the pre-trial detention executed through electronic monitoring.

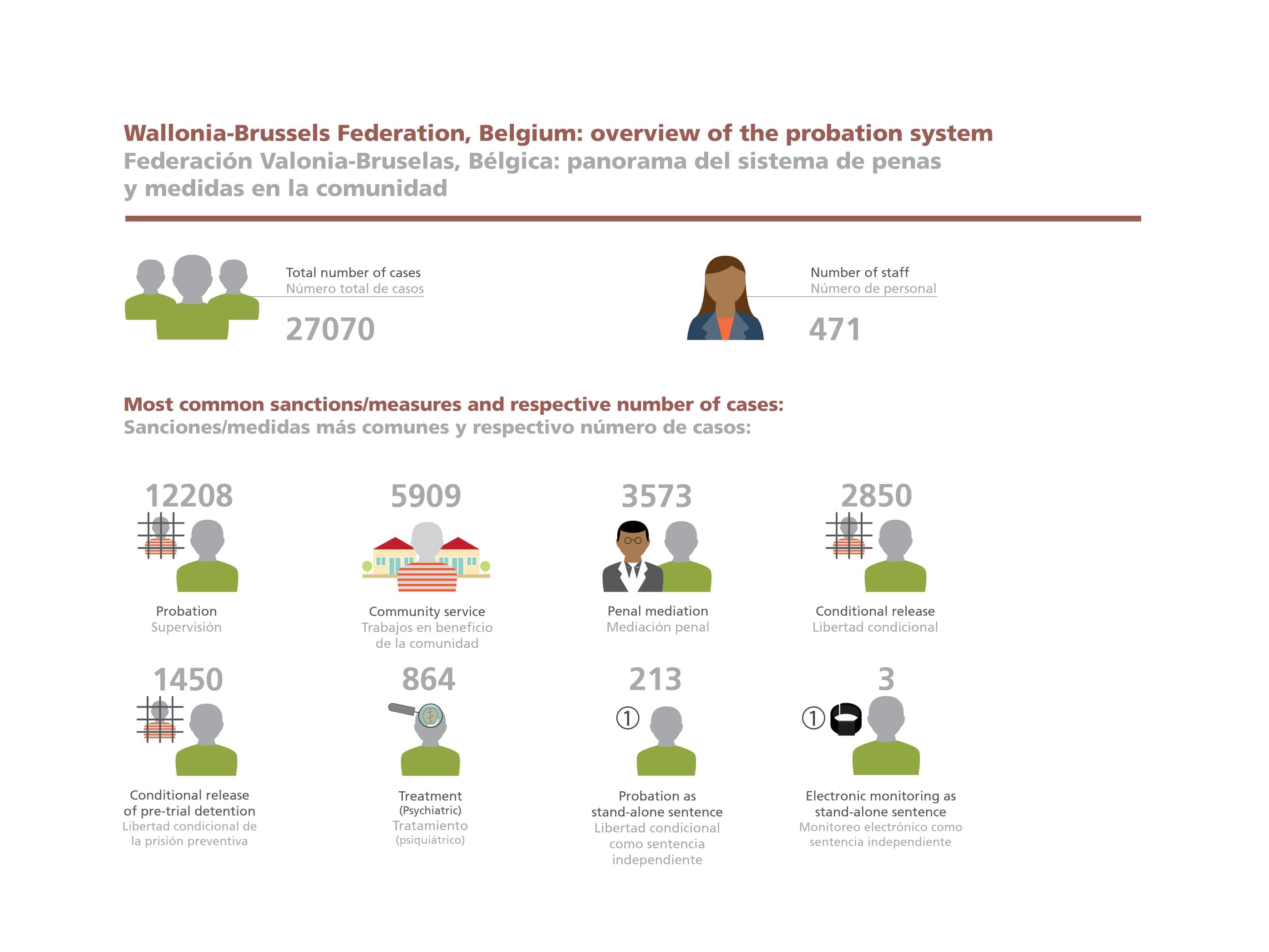

Since last year, we also have the electronic monitoring and probation as a stand-alone sentence, and also last year, we have witnessed a change in the law about mental health. And so, in the last three years, four new possibilities have arisen.

And, when I see the figures of SPACE II, it is incredible how Belgium is prolific not only in diversion measures but also in prison population figures. Although the statistics do not worry me, it is the meaning and the criminal approach that makes me wonder if we are on the right track.

JT: You mentioned electronic monitoring and it seems that it’s growing in different directions…

To what extent mobile and other modern technology tools are being used/will be part of the future of the probation officers?

AD: At the moment it is not the case, we don’t have any applications.

I would say that’s mainly because of the reorganisation and all the restructuring we’ve been undergoing.

Nevertheless, in the near future, it will be part of the reflection. I am sure it could only be beneficial if it makes the probation officers’ work easier and simpler and if it improves quality.

However, it will require some benchmarking, to have a clear picture of our needs and of the possibilities before implementing any additional technology.

//

Annie Devos is the Director General of the Houses of Justice of the Wallonia-Brussels Federation since 2006. She started her career at the Belgian Ministry of Justice in the late ’80s. She has experience in penitentiary advisory and as lead-manager of business process reengineering. Mrs Devos holds a degree in Social Science, a master’s in Criminology, and is frequently invited as a speaker in conferences at national and international level.