Noteworthy Practice

Ireland

Ireland has a comparatively low pretrial detention (PTD) rate by European standards, at around 14 pretrial detainees per 100,000 population.

While there has, rightly, been much attention placed on countries with high levels of pretrial detention, this piece argues that we need to examine why rates are lower in some countries than in others.

With a relatively low, though increasing, rate of PTD, Ireland offers some interesting potential lessons for other countries as well as policymakers at the regional and international level seeking to reduce PTD rates.

This article draws on a broader study of the use of PTD in Ireland, itself based on an examination of the use of this measure in seven European Union countries. It describes the use of PTD in Ireland and places it in a European context. It then reflects on some of the reasons which might explain the comparatively lower use of PTD in Ireland than that seen elsewhere. The article concludes with some reflections on what the experience of Ireland might offer to others.

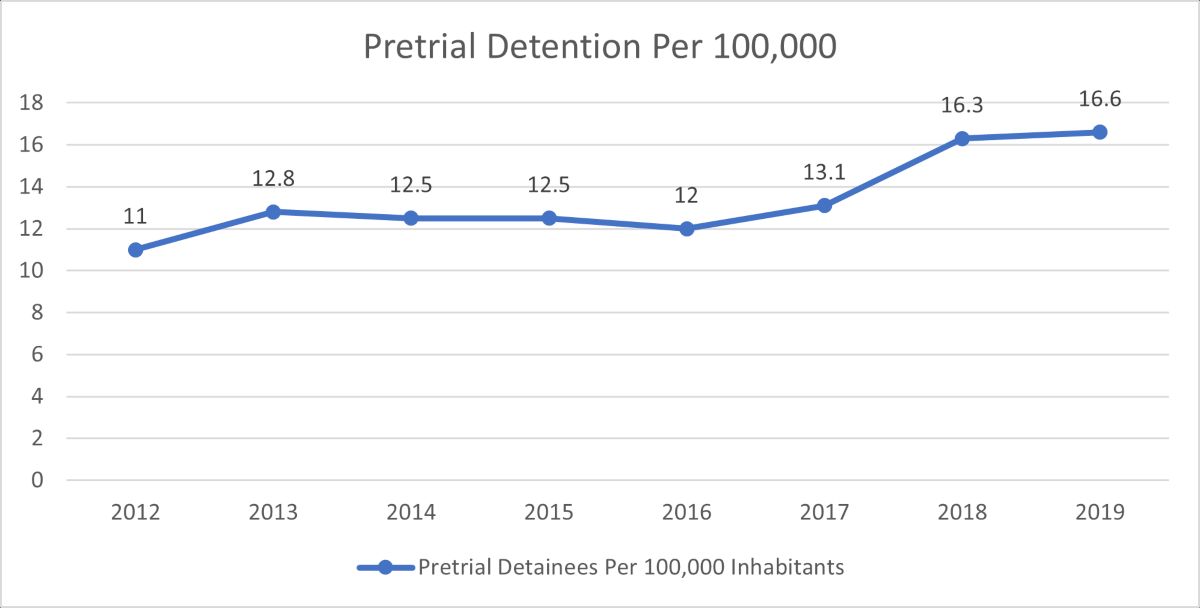

Ireland has maintained a relatively low PTD rate over recent years, though it has seen increases, as figure 1 indicates :

Ireland’s overall prison population rate sits around the Council of Europe average at 80 prisoners per 100,000 population (Council of Europe, 2019). PTD prisoners make up around 20% of the total prison population in Ireland. At the outset, it is important to note that Ireland does not presently use electronic monitoring as an alternative to PTD.

While provided for in law, electronic monitoring is not currently used at the pretrial stage. This position perhaps makes the comparatively low rate of PTD in Ireland all the more noteworthy.

Ireland is a common law jurisdiction, with its law on PTD being made up of statute, caselaw and constitutional principles and interpretation.

The term ‘bail’ is important to clarify. In many countries, ‘bail’ refers to the financial guarantee provided by a person or a guarantor to secure attendance at trial. In Ireland, the term ‘bail’ is used to describe the alternative to custody in its entirely.

Financial conditions may be attached, but a person will be described as being ‘on bail’ when not in PTD.

The legal framework in Ireland can be viewed as being one which favours liberty over detention, requiring specific reasons for the use of PTD. One might describe the position as obliging prosecutors to argue a person into detention rather than an accused person being required to argue themselves ‘out’. For example, a person charged with a criminal offence has a prima facie (on the face of it) entitlement to be released on bail pending the conclusion of the proceedings (Vickers v. DPP, 2009).

Bail is not an ‘automatic right’ of a person pending trial, it is still an important aspect of the individual’s constitutional right to liberty, a right which can only be restricted on limited grounds supported by cogent evidence’ (DPP v. Mulvey, 2014, para 40). The foundations of this approach are found in the highly consequential decision of People (Attorney General) v. O’Callaghan (1966). In that case, the Supreme Court of Ireland held that detaining a person in custody simply because he or she has been charged with a criminal offence is inconsistent with the presumption of innocence underlying the criminal law.

There are three main grounds upon which a person may be refused bail in Ireland. The first is where it appears likely to a court that the accused person will, if given bail, abscond or evade justice by failing to turn up for trial. The prosecution must satisfy the court that there is a likelihood that the defendant will abscond, though this need not be proven beyond a reasonable doubt.

A person may also be placed in PTD if a court considers it is ‘reasonably probable’ that the person will interfere with witnesses, jurors or evidence. Bail may also be refused where the prosecution satisfies a court that there is a real risk that the accused will commit serious offences if granted bail. The insertion of this ground into Irish law required one of the rulings in People (Attorney General) v. O’Callaghan (1966) to be overturned. The Supreme Court there held that it was unconstitutional to refuse bail on the grounds that it is necessary to prevent the commission of a criminal offence. In 1996, a referendum was held to reverse this position. The new legal ground to refuse bail was enshrined in section 2 of the Bail Act 1997.

Such an objection may be raised where the accused is charged with a serious offence and it is also apprehended that a serious offence may be committed. The Schedule to the 1997 Act lists a finite but extensive number of offences which are considered to be ‘serious offences’ in this context. These offences include murder, manslaughter, serious assaults, kidnapping, false imprisonment, rape, robbery, dangerous driving causing death or serious bodily harm, drug trafficking, firearms offences, theft, and sexual offences including rape and sexual assault. Irish law has been amended in more recent times to make it more difficult for people charged with the offence of burglary of a dwelling where that person has prior convictions and/or charges for that offence to obtain bail.

A wide and flexible set of conditions may be imposed on a person who is granted bail, including conditions to reside in or stay away from particular places, restrictions on contact, surrender of travel documents, and signing on with local police (Garda) stations.

While the legal framework in Ireland can be viewed as one which protects liberty, perhaps more important is the accompanying legal culture which seems to favour bail over detention. As part of a study on PTD in EU countries, a total of 26 interviews were carried out with judges, lawyers (from both prosecution and defence) and probation staff. Across all interviews, the constitutional position of bail and the presumption of innocence were cited as critical factors explaining the comparatively lower levels of PTD.

Avoiding PTD was seen by participants as being the norm, with admission to bail being the expected position, requiring something ‘extra’ to overcome the barriers to the imposition of PTD. Participants reported that the most important ground over which arguments about the use of bail would be made was the ground relating to the likelihood of turning up for trial.

This ground remains highly dominant in Irish legal discourse, with the introduction of the risk of offending ground in 1997 still being more peripheral, though increasing in importance in more recent years. In addition, participants felt that there was a broadly similar understanding amongst all players: judges, prosecutors and defence lawyers about what the important factors are when deciding on PTD.

For all of them, the most influential was the person’s prior record of turning up for trial or other court appearances. This factor is more important, in their experience, than the seriousness of the current charge, or the prior criminal record. It was also felt that there was, largely, a good degree of equality between the various parties; the prosecution was not felt to be overly dominant.

A common legal training for those who work as prosecutors and defence lawyers was viewed as one of the reasons for this picture, but also the fact that barristers (advocates in court) may take both prosecution and defence work. A kind of prosecutorial self-restraint was noted by participants, whereby prosecution lawyers were considered to be reasonably open to discussions about agreeing to bail in suitable cases.

While recent increases in the use of PTD in Ireland suggest that its low rates of PTD may be facing some threat, the study presented here suggests that the strong position of bail in both the Irish legal framework and legal culture is an important factor explaining its comparatively low rates of use of PTD.

Perhaps most notably, the ground of risk of offending has not proven to be very dominant or overwhelming in most decisions on PTD. This suggests that the risk of offending ground merits further analysis in other jurisdictions to assess its role in driving high PTD rates. As well as the formal legal framework, however, the experience of Ireland indicates the importance of legal culture in mediating against excessive use of PTD. In Ireland, participants reported a good level of procedural equality between the parties, but, perhaps more importantly, a legal culture in which the prosecution is not more aligned to the judiciary, nor more likely to succeed by virtue of its status as prosecutor.

This study suggests that while legislation and legal standards need to be tackled in efforts to reduce PTD, judicial and legal training as well as the culture of prosecutors and defence lawyers must not be overlooked.

Funding acknowledgment: Justice Programme of the European Commission.

Grant number JUST/2014/JAC/AG/PROC/6606

Mary Rogan

Dr Mary Rogan is an Associate Professor at the School of Law, Trinity College Dublin, Ireland. She leads a European Research Council-funded project called ‘Prisons: the rule of law, accountability and rights’. This work examines inspection, oversight and accountability in prison systems.

Dr Rogan is the President of the International Penal and Penitentiary Foundation.