Interview

Mauro Albuquerque

Secretary of Penitentiary Administration and Resocialization, State of Ceará, Brazil

The Brazilian state of Ceará is facing a worrying scenario, where crime and organised violence are exerting heavy influence within and beyond its prisons. This scenario, in addition to fuelling crime, violence and riots inside prisons, also has direct and significant influences on the security of Ceará’s civil society.

In January 2019, Secretary Mauro Albuquerque transitioned from his successful tenure overseeing the penitentiary system in Rio Grande do Norte, where he effectively addressed a comparable crisis, to assume the role of Secretary of Penitentiary Administration in Ceará.

In our conversation with the Secretary, we explored the strategies and results of his approach to maintaining order and security in the fight against organised crime, as well as the advancements made by the State Penitentiary Administration in the field of reintegration through education and work.

What was the panorama in Ceará’s prison system when you assumed leadership?

MA: When I took over the leadership of the prison system in Ceará, we found a scenario dominated by criminal factions that held overwhelming control over the prisons. The factions were divided into specific prison units, and only with this concession was the state able to offer some security for the prisoners.

There was a segmentation between the existing factions, namely the Comando Vermelho, the G.D.E (Guardiões do Estado), and the PCC (Primeiro Comando da Capital). Those who were not involved in any faction made up the fourth segment of the prison system.

This division ostensibly favoured the factions, allowing them to exercise their control under the guise of ensuring inmates’ safety. But the reality was different. Between 2013 and 2018, more than 200 prisoners lost their lives, an average of 50 deaths a year.

Furthermore, there was a proliferation of prison facilities, many of which were small and lacked the necessary infrastructure for healthcare, security, and inmate support. These units, in reality, functioned as criminal hubs, as there was virtually no effective oversight. A single prison officer was tasked with supervising hundreds of prisoners, an utterly untenable situation.

It is crucial to emphasise that the factions capitalised on these conditions within the prison system, which is a grave concern. Organised crime controlled everything inside the prisons. Inmates had to pay the factions for their own accommodations, and even for the food provided by the state. A black market for food and goods, such as fans brought in by inmates’ families, thrived within the prisons. The scale of the money involved was alarming, not to mention drug trafficking, which inside the prison system is worth 15 to 20 times more than on the streets. The factions also controlled crime on the outside, mainly through the use of cell phones, which I consider to be one of the most dangerous weapons in the prison system. This allowed video calls to be made and even executions ordered via mobile devices. In short, the prison system was completely infiltrated by the factions, to the point of preventing penal officers from entering certain areas and requiring the Public Prosecutor’s Office to enter with an armed escort from the riot police.

In the field of prison security, what were your priorities compared to the previous situation?

MA: The foremost priority was to dismantle the absolute control that criminal factions exerted within the prison units. We put an end to the practice of assigning exclusive units to each faction and instead implemented a wing-based separation approach. This measure signalled that the state was no longer subservient to any particular faction. Additionally, we began to close smaller prison units without adequate security.

The factions, knowing my work in Rio Grande do Norte, realised that I was committed to eradicating the privileges organised crime had garnered within the prison system. In response to our intensified efforts against the factions, the state faced a wave of attacks shortly after I took office.

We have raised the level of prison security and intelligence. We introduced a close surveillance approach, where penal officers are able to maintain constant contact with inmates while ensuring the officer’s safety through physical barriers. This marked a departure from the previous scenario where prisoners had complete control of the interior of the facility while penal officers remained outside. This proximity enables us to prevent aggression and promptly intervene in high-risk situations. It also facilitates other security activities, such as cell and inmate searches. Consequently, we have enhanced control over issues like contraband smuggling and the detection of escape tunnels, which were a significant problem in the past.

This transformation in security is pivotal in diminishing the influence of factions and curtailing their recruitment efforts.

When the state provides adequate security for those under its custody, individuals begin to realize that there is an alternative to submitting to criminal factions.

Furthermore, we bolstered our workforce by increasing the number of criminal police officers in prison units. In the past, some units were staffed with only nine officers responsible for managing 1,500 prisoners. Today, those same units have 35 officers on duty, with an additional 16 during the day, enabling a more robust and effective presence.

Security is the foundational pillar that allows us to play a crucial role in prison management and inmate rehabilitation. Only when security is assured can we effectively carry out reintegration initiatives and programmes.

What results have you obtained from these and other prison control and intelligence measures over the years?

MA: In recent years, the prison control and intelligence measures we’ve implemented have yielded significant and measurable results. One striking example is the drastic reduction in escape incidents. Previously, we had nearly 1,000 escapes a year, but over the course of these five years, we’ve successfully slashed that number to just 113. Most of these escape attempts took place during work or study activities, and out of the 113 escapees, we were able to recover 88 individuals through intelligence work.

Another pivotal area of progress was our battle against the proliferation of cell phones within prisons. In 2018, around 5,400 cell phones were seized. However, in the first quarter of 2019 alone, we had already intercepted 4,700 cell phones. This number dropped to 900 in the second quarter and further decreased to around 300 in the third quarter. By 2020, we had virtually prevented cell phones from entering prisons, a critical achievement in the Brazilian prison system.

Furthermore, we’ve adopted technologies like X-rays and body scanners to reinforce security and deter the entry of illicit objects into the cells. Simple measures, such as the removal of razors from cells, have helped prevent the use of these objects as weapons and escape tools.

The most significant result of these actions was the eradication of violent deaths within the prison system. After two incidents in 2019, we managed to maintain a period of three years without any fatalities within our prisons. This is an unprecedented achievement and demonstrates the success of the strategies adopted in the fulfilment of Mandela’s number one rule, which is the protection of everyone in the prison system.

When the state provides adequate security for those under its custody, individuals begin to realize that there is an alternative to submitting to criminal factions.

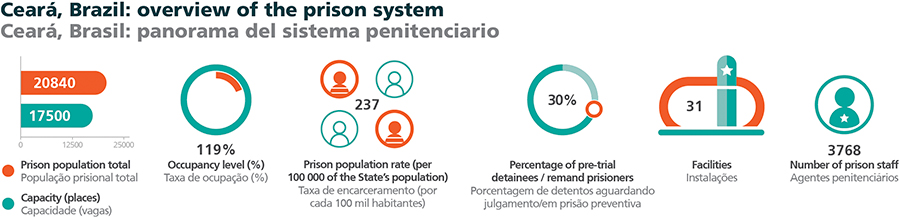

JT: Overcrowding in prisons poses a challenge for the state, mirroring the broader situation in the country. However, Ceará has made significant strides in addressing the shortage of available prison spaces. In 2019, there were nearly 20,000 missing prison places, but by 2022, this deficit had shrunk to approximately 5,000 places.

What measures have contributed to this development, both in terms of increasing the number of places available and reducing the prison population?

MA: In terms of the prison population itself, which previously numbered around 30,000 inmates, we undertook a substantial effort to review ongoing criminal proceedings. Many detainees were held for procedural reasons, lacking legal representation from the state and relying on lawyers connected to criminal factions, effectively keeping them under the factions’ control.

As we transferred prisoners from rural areas to the capital, we established an in-house legal team within the prison facilities, carrying out procedural reviews and referring cases to the Public Defender’s Office. Additionally, we expanded the use of videoconferencing to expedite the legal process. Since 2019, we have conducted over 125,000 procedural reviews.

As a result, before the onset of the pandemic, we successfully reduced the prison population from 30,000 to 22,000, marking a substantial reduction of over one-third.

Upon my arrival, there were 16,000 pre-trial detainees, accounting for more than 50% of the prison population. Some individuals had been incarcerated for more than five years with no progress on their cases. A considerable part of these reductions was achieved thanks to joint work with the judiciary. Joint prison inspections were conducted to assess the status of provisional detainees, leading to the release or transfer to semi-open regimes for many of them upon receiving their sentences.

Additionally, we expanded the prison system by approximately 6,000 places, maximising existing cell space while adhering to all prison construction regulations, rather than expanding the physical infrastructure.

Another focus of your leadership has been on education, training, and employment opportunities for incarcerated individuals. Could you elaborate on some of the advancements in this area?

MA: From the outset, we set out to improve access to education within prison units. We substantially increased the number of prisoners enrolled in classrooms, from 1,000 to 6,000. In addition, many of the prisoners had no professional training, which left them at a disadvantage when they returned to society. We chose to train inmates in areas such as construction, metalworking, and mechanics, among others, following the quality standards of SENAI, a respected educational institution in Brazil.

So we took the next step. If we’re already investing in the necessary resources, we’re going to build something with this person. And the money that I was going to spend just on inmate training, we invested in building and renovating prison infrastructure, which will be used by the inmates themselves. To put this into context, when we took office, we found units in a precarious state, some without an adequate structure for education or professional training. In some facilities, there weren’t even any classrooms. We faced the need to create new spaces to promote education and vocational training. To date, we have certified more than 23,000 prisoners in various skills, including metalworking, painting, plumbing, plastering, and much more.

The recidivism rate in Ceará has dropped to 23%, showcasing the success of these initiatives. Nonetheless, we face the challenge of combatting recidivism in the first 90 days after release, when many former inmates resort to crime in search of resources.

In summary, our action plan extends beyond the Penal Execution Law; it is a comprehensive public security strategy. Our aim is to educate, train, and transform, providing opportunities for inmates to build better lives and make positive contributions to society.

Mauro Albuquerque

Secretary of Penitentiary Administration and Resocialization, State of Ceará, Brazil

Mauro Albuquerque is a specialist in public security and prison management. He has held the position of Secretary of Penitentiary Administration and Resocialization of the State of Ceará since 2019. Having started his career in the Military Police in 1987, he joined the Civil Police of the Federal District (DF) a few years later. He founded the Federal District’s Special Operations Penitentiary Directorate, of which he was director between 2000 and 2015. He was also the founder and coordinator of the Integrated Penitentiary Intervention Force, which intervened in prisons in Ceará in 2016. In 2017-2018 he was Secretary of Justice and Citizenship for the state of Rio Grande do Norte.