Interview

Anne Kelly

Commissioner of the Correctional Service of Canada

JT: In November 2019 you stated: “The Correctional Service of Canada has begun a transformative era in Canadian federal corrections with the implementation of Structured Intervention Units (SIUs) as the new correctional model guiding our work with inmates who cannot be safely managed within a mainstream inmate population”. (1)

What does the new correctional model consist of, and how successful has it been so far?

AK: Our correctional system’s core mandate is to rehabilitate and safely reintegrate offenders back into the community. We focus on making our correctional facilities safe environments that support inmates in working on their needs and risk factors so they can become law-abiding citizens.

Some inmates cannot be safely accommodated in the general inmate population in our correctional facilities because of the risk they pose to themselves or to others. Correctional Service Canada (CSC) implemented an effective alternative that is really part of a historic transformation of the Canadian federal correctional system. It is important to me and a key obligation of the CSC, that all prisoners are treated with respect and dignity.

In November 2019, CSC implemented Structured Intervention Units (SIUs) and abolished administrative segregation. The SIU system was designed as a temporary measure to provide target interventions to support offenders in dealing with the underlying causes preventing them from living safely in the mainstream population. It helps us minimize situations in which inmates spend too much time in their cells, encourages meaningful human contact, and provides strong safeguards such as enhanced health services and external decision-making.

While in an SIU, inmates have access to the same types of programs, services, and activities as the mainstream inmate population. They are visited daily by staff, including their parole officer, correctional officers, primary workers, Elders and chaplains, as well as other inmates and visitors. The model also empowers our healthcare practitioners, who visit them daily, to monitor and make recommendations on an inmate’s conditions of confinement.

By law, inmates in an SIU are allowed to spend a minimum of four hours a day outside their cell, including two hours a day for meaningful human contact.

The legislation also recognizes that there are situations when an inmate may be held in their cell for longer. This includes those circumstances when they refuse to leave, which is their right. If an inmate does not meet the four hours out of cell or engaged in meaningful human contact with others for a minimum of two hours for five consecutive days, or 15 out of 30 calendar days, their situation is reviewed by an Independent External Decision Maker (IEDM).

IEDMs are an important safeguard built into the law. This cannot be understated. They provide oversight of an inmate’s conditions and duration of confinement in an SIU. They monitor and review inmate cases on an ongoing basis and provide recommendations and binding decisions to the CSC. The Correctional Investigator also provides oversight of federal corrections.

Moreover, some SIU sites are benefiting from significant involvement by volunteers and community organizations. They have introduced therapy dogs, workshops, art, social activities, and increased access to video visitation and telephones to connect with their supports.

We are always looking to improve and conduct an ongoing evaluation of the new model, including an audit of our SIU policy and operations that will help identify changes needed.

Overall, I am confident that we are moving in the right direction.

JT: While accounting for 5% of the general Canadian population, the number of federally sentenced Indigenous people has been steadily increasing for decades. More recently, custody rates for Indigenous people have accelerated, despite declines in the overall inmate population, reaching a new historic high in 2020, surpassing the 30% mark. “Consistently poorer correctional outcomes for Indigenous offenders (e.g. more likely to be placed or classified as maximum security, more likely to be involved in the use of force and self-injury incidents, less likely to be granted conditional release) suggests that federal corrections make its own contribution to the problem(…)”. (2)

To what extent does the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC) dedicate programmes and specific services to the Indigenous population in its care? How can the CSC contribute to reverse the issue of overrepresentation that this population has in the federal correctional system?

AK: Our commitment to making a positive impact on Indigenous peoples serving a federal sentence is extremely important to me.

The overrepresentation of Indigenous peoples in our criminal justice system is unarguably a systemic issue that requires interventions at multiple levels, including in federal corrections. I am dedicated to making a change in any way that we can, and we are exploring innovative approaches to addressing this issue.

We are working closely with other federal, provincial, and territorial government departments, and we continue to increase collaboration with Indigenous communities and organizations. We recognise that a whole-of-government effort and partnerships with Indigenous peoples are essential to addressing underlying causes and help reverse the issue of overrepresentation.

I firmly believe that by increasing this horizontal collaboration, we will gain insight into best practices and opportunities to address social determinants of health, including employment, housing, and physical and mental health, which are significant contributing factors to conditional release.

We recognize that Indigenous offenders have specific cultural and spiritual needs, and other considerations that have contributed to bringing them in contact with the justice system.

I have seen positive and incremental change within the organization since I started as a case management officer, now referred to as a parole officer, in 1983.

One of the shifts happened in 2003, when we introduced the Indigenous Continuum of Care model that focusses on culturally responsive programs and approaches to address the needs of Indigenous offenders. Integral to that are Elders and spiritual advisors who provide spiritual, ceremonial, and counselling support and teachings to First Nations, Métis, and Inuit offenders.

We have also facilitated restorative justice and supported the development of community-based and culturally relevant projects with a focus on alternatives to incarceration, including healing lodge methods.

We also work closely with Indigenous communities to facilitate and support the conditional release of Indigenous offenders and to strengthen those interventions, correctional policies, programs, and operations designed to support them. In addition, our Indigenous Correctional Program Officers are essential in the delivery of programs.

Overall, we are making progress across the spectrum of services and interventions designed and dedicated to supporting the Indigenous population in our care, but recognize there is more work to do.

What other challenges are there to face in the Correctional Service of Canada?

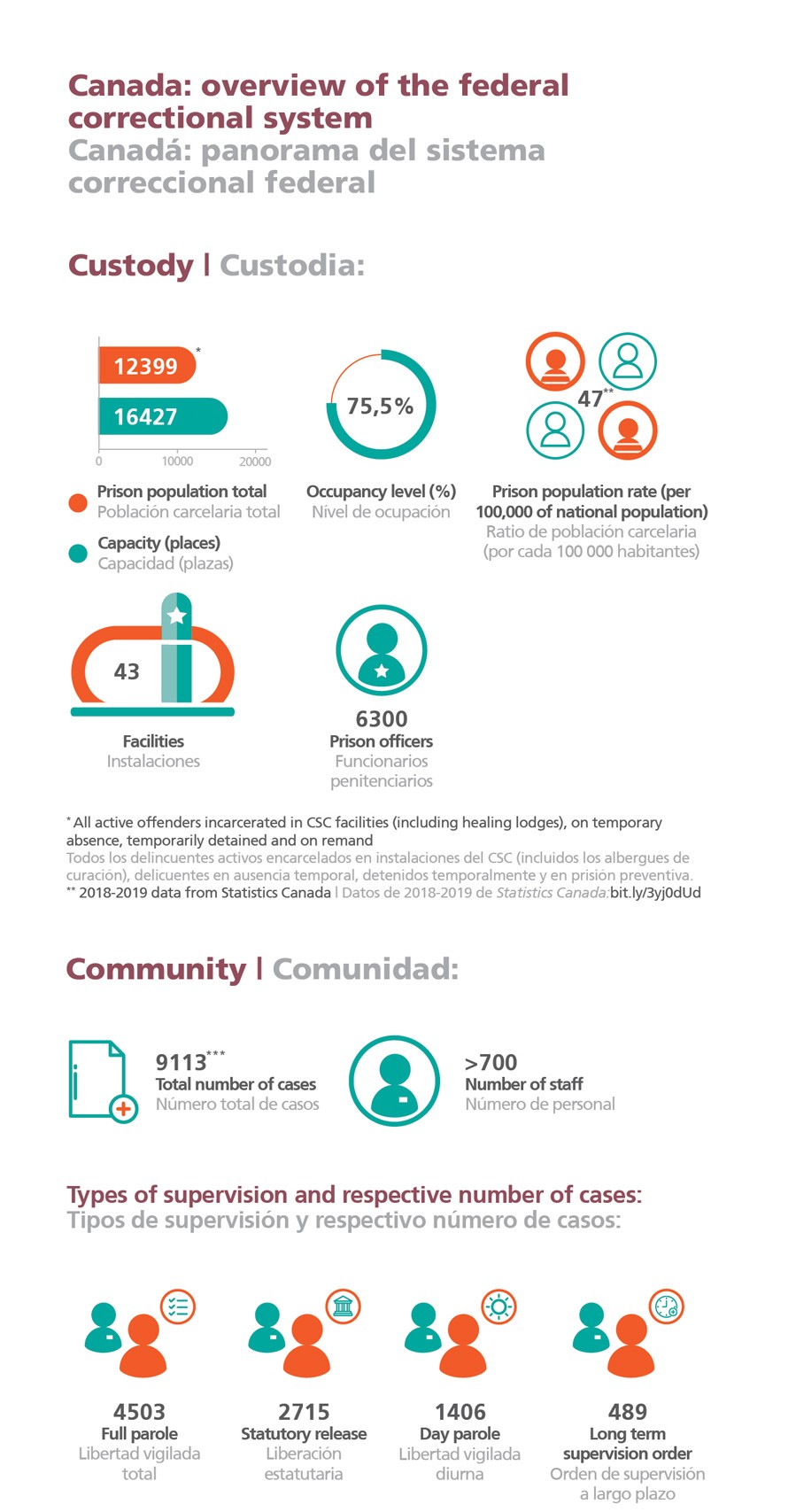

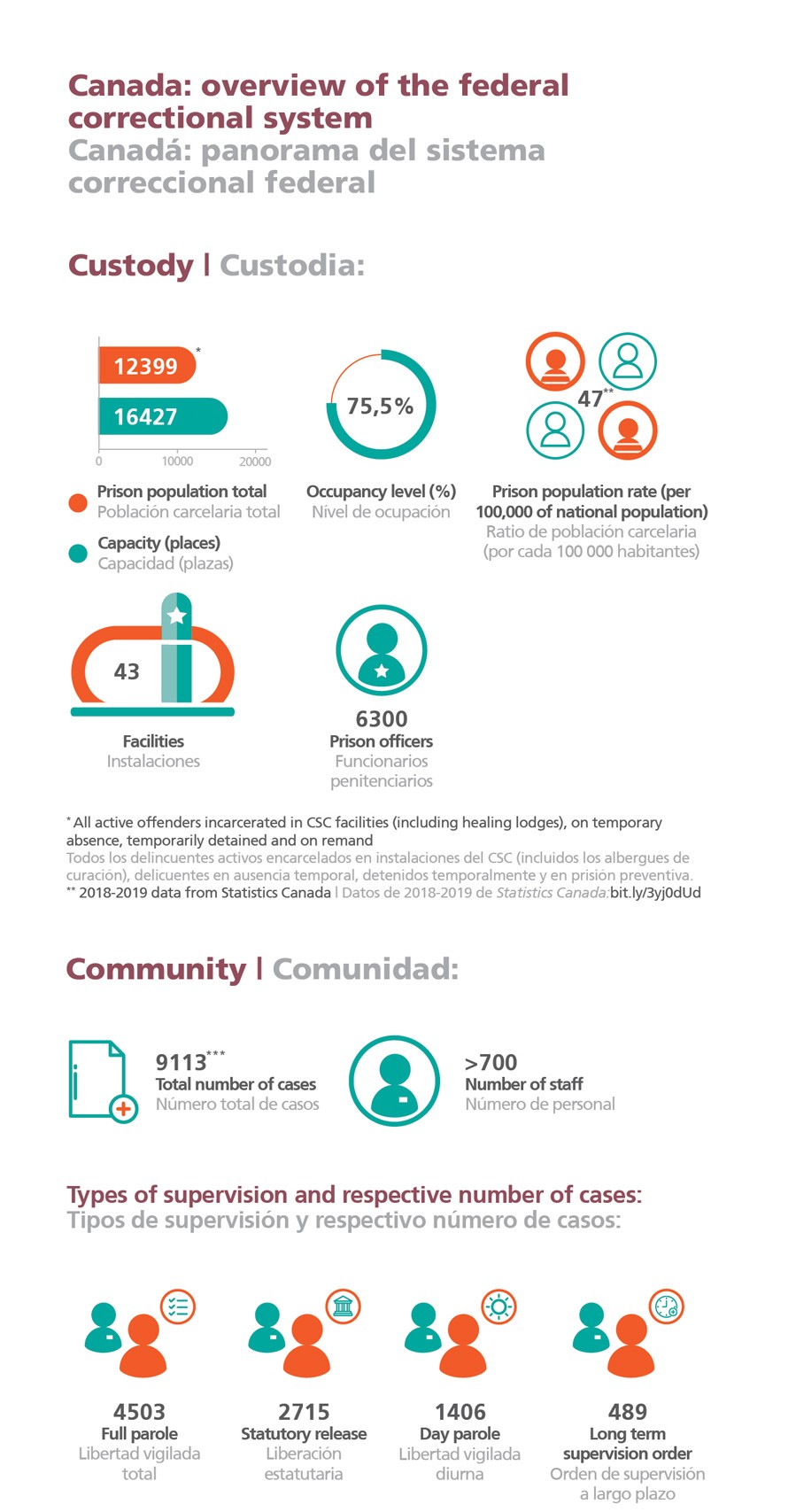

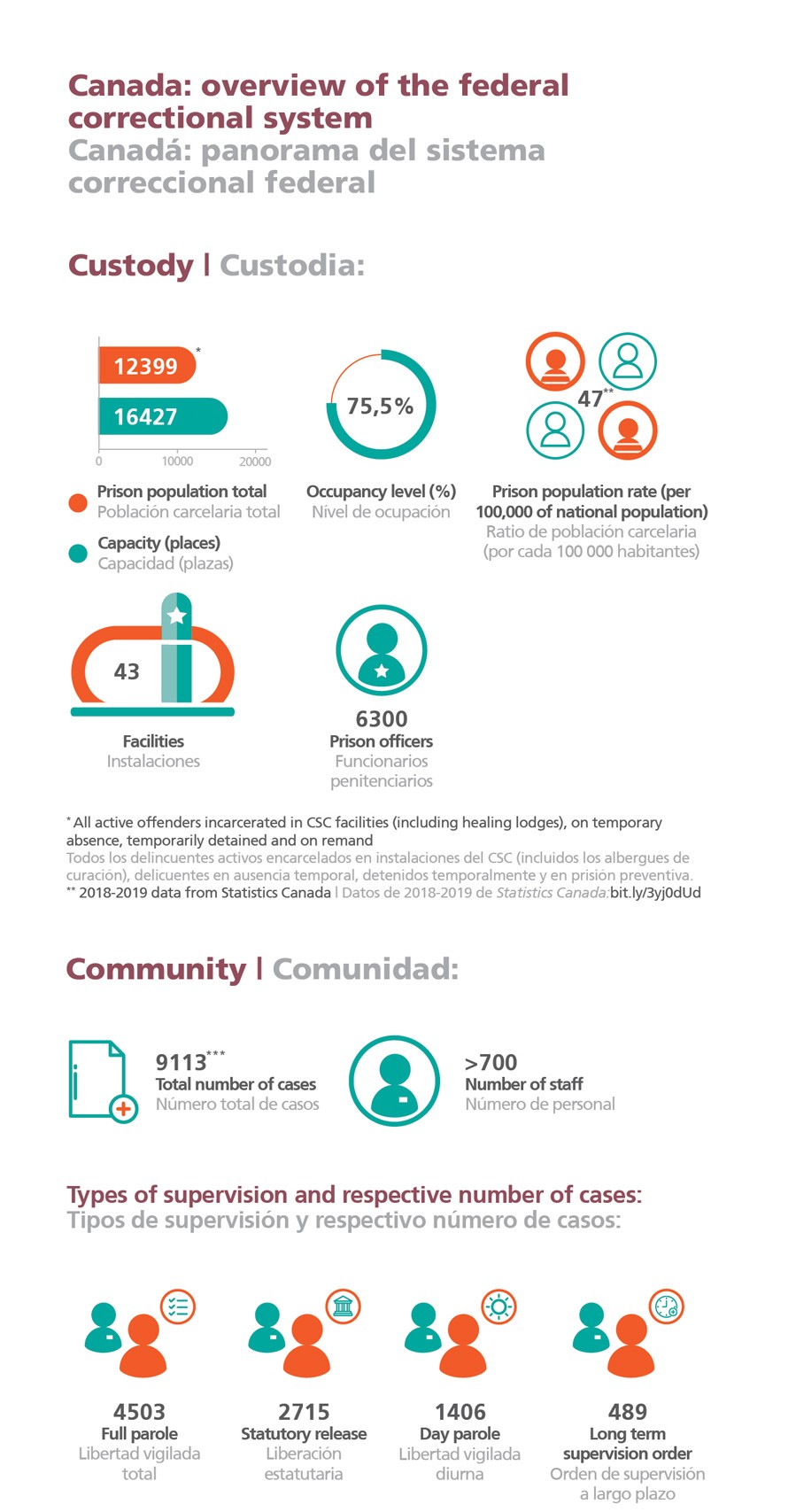

AK: First and foremost, we face the challenge of maintaining operational safety and security levels in our 43 institutions and in our community facilities.

Our offender profile is complex and diverse, and CSC’s task is to meet their rehabilitative, security, health, and address their individual needs and risks.

CSC also maintains a safe, secure, healthy, respectful, and collaborative working environment. It is very important to me that we actively promote an organizational culture that is anti-racist, combats harassment and discrimination, and fosters an atmosphere of professionalism and respect.

Anti-racism and anti-discrimination initiatives are all the more important given the increasing diversity of CSC offenders and staff – and the inherent need to build a culture where people can thrive and better themselves.

Through research, engagement, and communication, we are continuously finding ways to ensure that we meaningfully address the challenges faced by Black, Indigenous, and other racialized Canadians in our custody.

One of our key rehabilitation programs is CORCAN, which provides offenders with employment and employability skills training while they are incarcerated and, for brief periods of time, after they are released into the community. The pandemic posed challenges for CORCAN, but it found novel solutions using telephone and video-based options to provide employment skills programming and ensure offender accessibility to employment coordinators.

CSC also provides offenders with educational programs to help them develop literacy, academic, and personal development skills to help them successfully reintegrate into the community. The pandemic posed challenges in providing in-person education, so we explored options in distance learning and the supervised use of information technology.

We enhanced offenders’ computer skills and allowed offender-oriented programs to continue during the pandemic. I am proud of the innovative response of our various sectors and volunteers in adapting to the challenges of this past year.

New approaches and models were used to connect with offenders virtually, which allowed us to continue benefiting from external involvement in our operations.

With the increased digital demands, we are working to incorporate the appropriate technology infrastructure to move CSC towards a more efficient, effective, flexible, and digital correctional model.

JT: Over the past 5 years, the average number of supervised offenders under community corrections has increased between 18.5% and more than 37%, depending on the type of sentence. (3)

How much do community corrections weigh in the CSC? What investments have been made at this level, and towards what future are community corrections being guided?

AK: Public safety is paramount. Most offenders will return to the community, community corrections are a critical component in ensuring public safety.

We provide services that include accommodation options, community health and intervention services, and the establishment of community partnerships. We manage offenders on parole, statutory release, and long-term supervision orders.

We provide supervision strategies, interventions, and programs that address individual needs and risk factors and facilitate the transition and reintegration of individuals back into the community.

I am pleased to report that CSC is seeing historically high numbers of offenders supervised in the community. As of January 2021, the community offender population was 9,269, which represents approximately 42% of the entire offender population.

We use a Community Based Residential Facilities Program, which contributes to community supervision by providing accommodation to offenders. These are operated by non-governmental agencies under contract with CSC and promote the successful reintegration of offenders into the community. Community Residential Facilities (commonly known as halfway houses), treatment centres, hostels, private home placements, and supervised/satellite apartments fall under this residential program.

Community accommodations also support the needs of more complex and vulnerable populations, such as ageing offenders, women, and those with mental health or substance abuse concerns.

We recently developed the Offender Accommodation Management System, which ensures that consistent information is available to everyone involved in the release planning process and the supervision of offenders. It provides information for the placement of offenders in accommodation options that meet their needs at the right time of their sentence and in the right location.

Given the demands of today’s digital world, what is the state of play of CSC concerning technological modernisation, both at the operational level and in the context of rehabilitation and reintegration of the inmates?

AK: In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic catapulted CSC into its digital future. It forced us to assess the challenges and benefits of digital services for both staff and offenders, and I am proud of how quickly our information management team responded and adapted to the ever-changing situation. We needed to find solutions for the hundreds of employees who suddenly found themselves working remotely.

In addition to sourcing and purchasing new IT equipment, we had to increase our bandwidth to handle the amount of telework required. By adopting a new suite of office and productivity applications, employees were able to communicate through chat, audio, video calls, or work on documents in real-time with colleagues.

With the increased digital demands, we are working to incorporate the appropriate technology infrastructure to move CSC towards a more efficient, effective, flexible, and digital correctional model. We have also embarked on a multi-year journey to replace our Offender Management System – our mission-critical system – to update our business functions, services, and data.

We also brought digital innovation inside our institutions. We pivoted to increased video visitations, so offenders could connect with their loved ones and support networks, when visits were suspended during COVID-19.

We implemented more video visitation kiosks across the country and they are being well used. Before the pandemic, we averaged 1,200 video visits per month. After March 2020, they averaged 6,000 per month, peaking in May 2020 at 7,160.

COVID-19 also posed a challenge to our work with the courts. We expanded our Video Court equipment across the country, and worked with the justice system to increase its use to include witness testimony, appeal hearings, and entry of pleas.

We also collaborated with the Parole Board of Canada to enable virtual hearings, and the delivery of offender programs that are part of the offender journey to become eligible for parole.

Switching to Virtual Parole Officer Induction Training helped us ensure that CSC has sufficient parole officer staff available. A Virtual Integrated Correctional Program Model training was offered to correctional program officers to minimize the delay in addressing offender correctional programs’ needs.

We are now developing a Virtual Correctional Program Delivery project to transform our traditional, classroom-based approach to an interactive virtual platform environment.

In the wake of COVID, we expanded the telemedicine program, which provides physical and mental health services. We implemented an Offender Video Kiosk, in 13 locations across Ontario, to accommodate mental health assessment, and will deploy an additional 51 kiosks across the country. There is no doubt that these kiosks ensured continuity of care and reduced the footprint in local hospitals.

JT: The COVID-19 pandemic has brought significant challenges to correctional services worldwide.

Given the restrictions resulting from the pandemic crisis, what kind of measures have been implemented in Canada?

AK: From the outset of this pandemic, CSC has taken a proactive approach, guided by public health authorities, to ensure the health and safety of staff and offenders in all of our institutions.

At the start of the pandemic, we immediately suspended visits into our institutions and established extensive infection prevention and control measures across our institutions. These include mandatory mask wearing for inmates and staff, physical distancing measures, active health screening, and training over 250 employees to conduct contact tracing.

We completed independent, expert-led Infection Prevention and Control or Environmental Health reviews at each of our 43 institutions and ensured that all recommendations were implemented.

We also developed an Integrated Risk Management Framework, in collaboration with the public health authorities, our stakeholders and our Unions, which is used to make decisions on the activities (e.g. visits) that can take place or have to be placed on hold. We also carried out significant testing among inmates and staff, including asymptomatic individuals.

CSC provides its own health care to inmates and has dedicated healthcare professionals in its institutions, including nurses and doctors, who closely monitor anyone diagnosed with COVID-19. Moreover, we were an early adopter of rapid tests.

In January 2021, we began offering COVID-19 vaccines to older, medically vulnerable inmates. Soon, we expect all inmates will have the opportunity to be vaccinated, as more vaccines become available to us. Protecting those in our care and our employees is a top priority, given they live and work in congregate living settings.

Through mass testing, our infection prevention and control measures, and prevention and awareness, we have been able to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 in our operations and keep everyone as safe as possible. It has been a challenging year, and I am incredibly proud of our collective efforts.

(1) Correctional Service Canada. (2019). Correctional Service of Canada opens Structured Intervention Units and enhances health services for inmates. Ottawa.

(2) 2019-2020 Annual Report – Office of the Correctional Investigator

(3) Correctional Service Canada. Quick Facts Community Corrections [PDF].

Anne Kelly

Commissioner of the Correctional Service of Canada

Anne Kelly has a long career in the Correctional Service of Canada (since 1983), and she has worked at the national headquarters since the late nineties. She has been Director of Institutional Reintegration Operations, Director General of Offender Programs and Reintegration, and acted as Assistant Commissioner of Correctional Operations and Programs. She was also Deputy Commissioner for Women and Regional Deputy Commissioner. She was appointed as Senior Deputy Commissioner in 2011, and in July 2018, she was appointed Commissioner.