// Interview: Joerg Jesse

Director General, Prison and Probation Administration of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Germany

JT: Unlike many prison systems, yours is competing with other industries for job applicants, since many people actually want to be prison officers.

Why is the prison officer job so wanted, and what do applicants have to have to get it?

JJ: First, I think our applicants look for stability and a secure job as a civil servant, which is very attractive compared to jobs in the industry, as these tend to depend on the economic situation and other instabilities. The second reason is that they want to carry out a professional activity for a long time and that they care about contributing to the change in offenders’ lives. Many of our correctional officers see the work with troubled people to be challenging and interesting.

Only 10% of the applicants pass our recruitment assessment and usually, they all have had jobs in other specialities for several years. They need to have an IQ of at least 100, and they undergo two years of training. In the end, our officers are agents of change and that is what we want them to be.

Our prison officers need to have an IQ of at least 100 and they undergo two years of training.

JT: One of the current concerns in Europe (including the Council of Europe, the Council for Penological Cooperation and EuroPris) is the need to have standards regarding the selection, recruitment and training of correctional staff.

What do you think about this goal and what challenges should be overcome to achieve it?

JJ: I would very much appreciate a standardised training duration for prison officers in Europe, or at least the establishment of some rules through answering pivotal questions such as: “what do we need?”, “what do they have to learn?”, “what are their core competencies?”.

We have examples for that in the Council of Europe Recommendations, in the European Prison Rules and in other recommendations’ documents. In addition, prison officers should have the same salary level as, for example, police officers.

Regarding the difficulties that arise between the goal and its concretization: it takes a lot of work and money to create a professional recruitment and assessment system, and a long-term training curriculum. We’d need a consensus about the duration of the training and profile standards such as the educational level and further criteria. It is unbelievable that there are countries without any minimum entry level, nor training. Such leads to completely unqualified people having to deal with the most challenging people in our society.

Moreover, as long as we don’t have the same level of understanding of what a prison officer is, there are difficult obstacles to overcome. There’s a wide range of conceptions towards prison officers across Europe: we have countries where they just stand there with a baton in their hands not talking to prisoners.

That’s not my vision of a good prison officer. They have to be excellent communicators, they should give opportunities and be role models. Prison officers of any system are crucial to everyday life of the institutions, so they deserve a much better reputation.

JT: How do you feel about some jurisdictions looking up to your system as model and trying to transfer some of its best practices?

JJ: We all have our problems and challenges. I do not know a correctional system – even the best ones – that is perfect. However, I admit that there is a certain interest regarding the way we recruit, assess and train our prison staff, especially the officers.

The quality of our staff is rather impressive especially for my American colleagues. I suppose they look up to our sense of mission. To draw an example: they were impressed that everyone, from the prison officers, to social workers, to psychologists, to the prison governors, answered the question “What are you here for?” with “They (the prisoners) shouldn’t come back”.

In our system, prisoners have better chances when they are released, so it was a surprise for the Americans – and sometimes for some other European States – that we don’t talk about punishment. We talk about change.

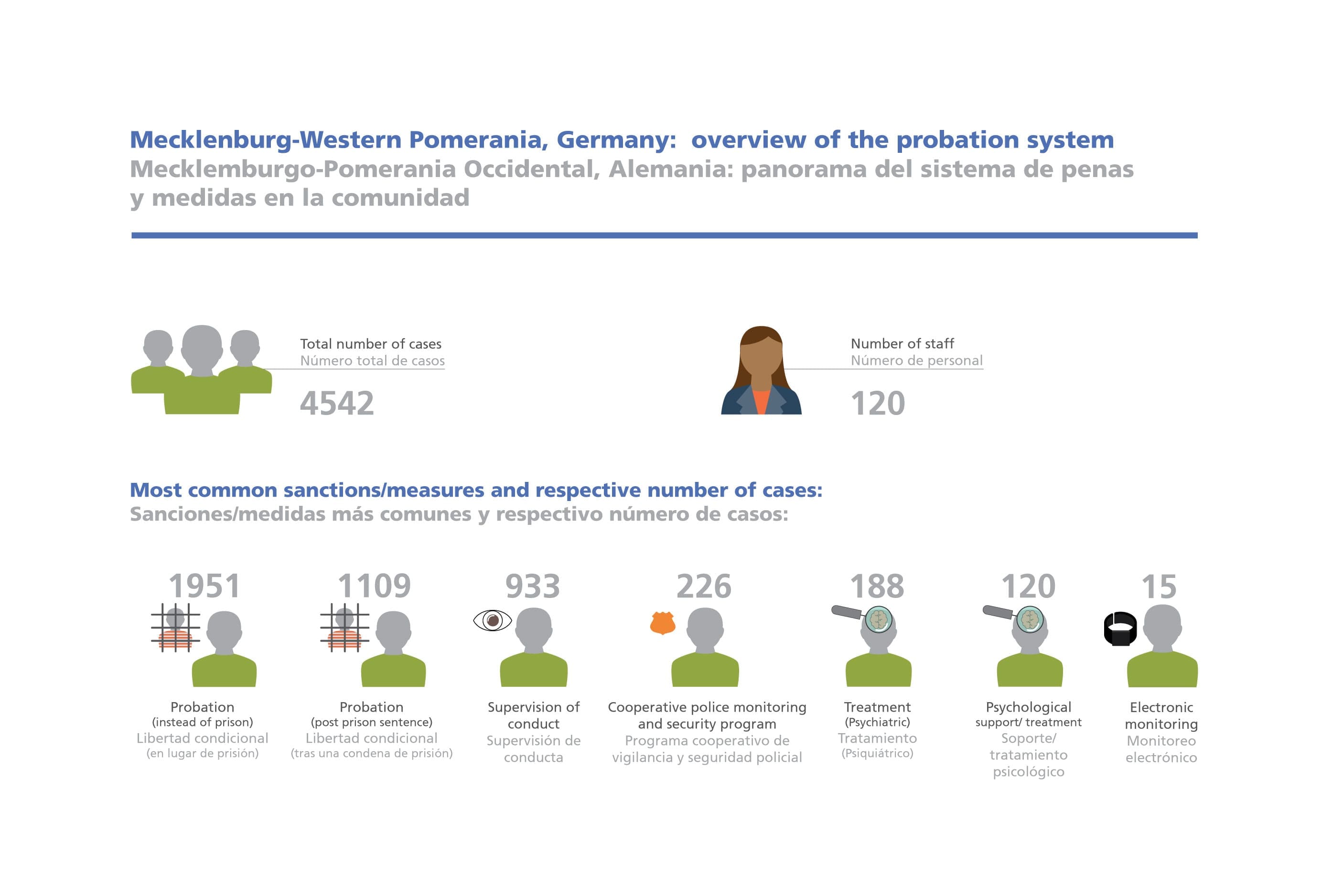

Another feature of our system is our close collaboration between our internal (prison) and external (probation) staff. We have fixed and binding rules at the beginning of the prison sentence and at the end or before release.

Probation works together with prison which means that if someone was on probation, failed and is facing a prison sentence again, probation officers work closely together with the sentence units. At least one year before release, probation staff has to work together with the prison release department to plan and organise the offender’s reintegrating into society as smoothly and seamlessly as possible.

I don’t think we’re better than others are. I believe we do our job and we have enough problems of our own. We are not perfect, but in the end, when we have visitors from other countries I am proud of my staff feeling proud.

JT: Which are the main deterrents to implementing the way your system works in any other jurisdiction?

JJ: Implementing the features of our correctional system takes time, a lot of work, and it also takes money – it is a long-term investment just to change the recruitment, assessment, and training process. Furthermore, many countries lack job specifications, profile, and qualifications criteria for prison officers, which are fundamental in our system.

Concerning the organisation itself, I think it needs top-down and political decisions. Many administrations in Europe have separate administrations for prison and probation. We have the same in Germany, except for my state and a few others who have both services under the same system, which I believe to be much more effective.

Thus, creating a unique prison and probation system also calls for political decisions, and I think there is a lot of resistance against that. Politicians often avoid to face hard decisions. Resistance to change is one of the main obstacles.

JT: Germany has one of the most progressive prison systems for youngsters. Throughout Europe, juvenile sentencing laws cover people until they are 18, whereas in Germany that age is 21, and there’s currently a political debate underway about raising that age up to 24.

What is your system’s approach to juvenile offenders?

JJ: In Germany, a person is a child up to the age of 14, so that’s the first difference in relation to the European and the worldwide standards, including the Mandela Rules. Consequently, our criminal justice system itself starts at 14.

In the next stage, from 14 to 18, the person is a juvenile and has responsibility for any crime committed. Then, between 18 and 21, it is a court decision – with the assistance of a psychological or psychiatric report by an expert – whether the person is considered a juvenile or an adult.

This leads to a prison population, in our facilities for juveniles, where there’s actually few juveniles (aged between 14 and 18 years); I would say it is less than 20%, and in my state, it is less than 10%. Slowly, these figures change the whole system, as we have to think about detention facilities for young adults instead of for juveniles.

Three decades ago there was 50% or more of 14 to 18-year-olds in juvenile establishments, however, our sanction system has evolved in a very successful way, as judges have a wide “toolbox” of different sanctions for youngsters. So, the average age of the ones who are in our “juvenile facilities” rises and rises.

Moreover, if, for instance, someone is sentenced to three years in prison when he is 20 or 21, we try to hold him in a juvenile prison, because he would have the chance to start a vocational training course and we’d try to hold him in there until he finishes it. I dare to say that in some of our juvenile facilities there are people who are older than 24 because of this situation.

Presently, I and my colleagues from other states are even discussing if we could take into juvenile facilities prisoners up to the age of 30, depending on the crime and if they are in prison for the first time.

I dare to say that there is no real juvenile prison system in Germany anymore and I am happy that this is the case.

JT: How are Germany’s correctional services organised?

JJ: Each state has its own correctional administration and although we don’t have a central coordination body nor a Board, we do have to report to the Ministry of Justice Conference twice a year. If there is something to decide by the ministers, we report to the Ministry of Justice and then they will decide; and if there are international topics, then the Federal Ministry is responsible.

There are no significant differences between states, since state prison laws – concerning their aims and content – are very similar. Furthermore, I am in very close cooperation with my fifteen colleagues; we meet at least twice a year, and we have a lot of telephone and email contact. There is a high standard of loyalty and cooperation on the one side and on the other there’s a bit of competition, especially regarding the best practices.

Even when it comes to the transfer of inmates or to the issue of terrorist offenders, the fact that we have different administrations does not pose any problems. If I have a very difficult inmate, for example, who is dangerous and problematic, I call any of my colleagues and request a change for that given inmate, I ask if he can be sent around. Another time, it might happen that I receive a call with a suchlike request.

We address these matters in an effective and smooth way. Likewise with imprisoned terrorists; we have learned our lesson with the Red Army faction in the 70s. We avoid centralisation of terrorist convicts: we don’t put them in the same department or unit, instead we’re constantly disseminating them and sending them around, so that they cannot build structures nor influence others, but we ensure we deal with them in a human way.

In short, loyalty and cooperation are the words that best describe the relationship between all of us directors-general of Germany’s correctional services.

JT: Being an Advisory Council Member in the Safe Alternatives to Segregation Initiative leads you to visit the United States of America’s prisons often, to consult on prison reform, including reducing solitary confinement. You have said that you consider that in the U.S. there’s a strange belief that punishment is changing something.

Why do you think that happens?

JJ: Compared to the European countries, the United States has a much shorter and different History; it is a country of immigrants, of many different cultures, personal histories and developments, etc. To generalise, they are a more punitive society. They go by the “law and order thinking”, and they have a strong belief that punishment alone can change behavior – which is the strangest thing, given that every psychologist would tell you that this is wrong.

On the other hand, we see the Safe Alternatives to Segregation Initiative: it is wonderful and very impressive to watch that a strong wave of change is emerging. I believe that the directors-general over there are writing History in the field of corrections. When we started the Initiative, there were just a handful of states that joined in, and now there are 15 or 20.

A very positive thing Americans have is that they are very consequent, enthusiastic and powerful – they create and organise change in a way that is impressive, and much quicker than it could be in Germany. Therefore, if they decide that something is not right and start a change, many good results can see light regarding correctional matters.

I think that the punitive approach to incarceration in the US is not shared either by the generality of directors-general nor by their staff; it’s the public opinion, the media, and the politicians, who depend on both the media and the public opinion.

We are not the ‘washing machine of society’ that is single-handedly responsible for behavioural change!

JT: What are the main challenges of the correctional sector in Germany and how do you see the future?

JJ: I think there has to be a stronger social awareness about the purpose of prison sentences and probation work. Such awareness includes the fact that prisoners’ reintegration is a duty of the entire social system and not a job of the correctional system alone. We are not the “washing machine of society” that is single-handedly responsible for behavioural change!

Society thinks we have to organise change within a few years of imprisonment of highly problematic individuals who come from municipalities with many unsolved problems and broken socialization processes.

Such processes take years, sometimes decades, and responsibility for reintegration lies across several institutions. I think that there’s a big lack of responsibility in these municipalities, so, we have to work with them, and to explain that they’re part of the solution. In this regard, we still have a long way to go.

Additionally, we have to talk with several Ministries: Labor, Social Affairs, Interior, and Education because they’re all responsible. We already put a lot of pressure on our staff and it is naive to believe that a prison sentence of two or three years will change offenders lives.

Further challenges have to do with the need to integrate and stabilise restorative justice schemes in the prison and probation services, the reduction of imprisonment, the increase of alternative sanctions and measures, and the increase of probation.

//

Joerg Jesse is the Director General of the Prison and Probation Administration of the German state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania since 2003. Mr. Jesse has been working in corrections since 1983 in a variety of areas: facilities for juvenile offenders, prisons, at the Headquarters, and in the Ministry of Justice. He is a member of the PC-CP since 2011 and Vice Chair since 2015. He is an Advisory Council Member of the Safe Alternatives to Segregation Initiative, since 2015.

Advertisement