// Interview: Torben Adams, Radicalisation Awareness Network (RAN)

Co-chair Prison and Probation Working Group (P&P), RAN, European Commission

JT: What is RAN?

TA: The Radicalisation Awareness Network (RAN) is a network of frontline practitioners who work daily with people who have been radicalised, or who are vulnerable to radicalisation. The network brings together practitioners from Europe and beyond working on our mutual goal: the prevention of radicalisation and the disengagement from violent extremism.

Involved practitioners include prison, probation and police authorities, but also those who are not traditionally involved in counter-terrorism activities, such as teachers, youth workers, civil society representatives, representatives of the local authorities, and healthcare professionals.

The RAN Centre of Excellence (CoE) is funded by the Internal Security Fund – Police, from the European Union, and is leading RAN. RAN CoE is guiding the different thematic RAN Working Groups, and one of those is the prison and probation Working Group. RAN CoE also supports the EU and individual countries when requested on the dissemination of gathered key-knowledge.

JT: What is the RAN Prison and Probation Working Group (RAN P&P)?

TA: The Prison and Probation working group brings together practitioners from the prison and probation sector such as prison and probation officers, governors, psychiatrists, social workers, vocational and educational instructors, chaplains, and other related disciplines.

The Working Group focuses on supporting these practitioners, who have a role in preventing radicalisation and disengagement from violent extremism. The group exchanges ideas, best practices, contacts and insights to formulate recommendations for policymaking. The intention is to be a strong platform for the world of practitioners, researchers and policymakers to pool expertise and experience to tackle radicalisation.

We follow the European Commission’s Communication on Preventing Radicalisation to Terrorism and Violent Extremism as well as the European Agenda on Security, as this provides us with our policy framework for the EU’s prevention policies.

JT: Who is part of the RAN P&P Working Group?

TA: Our Working Group comprises approximately 400 practitioners including representatives from prison administrations, probation services, ministries of justice and intelligence services, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and civil society organisations (CSOs) working with offenders.

A one-size-fits-all solution applicable across all EU Member States is of course not feasible.

Member States vary in legislation, standard operating procedures and organisation of their prison and probation systems. This is also blatant when practitioners meet in the framework of RAN.

Our aim is to offer a platform where practitioners meet and discuss. The purpose is that participants are stimulated and encouraged to contribute to meaningful policy development in their countries.

The Prison and Probation Group is benefiting greatly from the rich expertise of Ms. Fenna Canters and Mr. Maarten van de Donk from the RAN CoE.

I have the privilege to co-chair the Working Group together with my colleague Dr. Ioan Durnescu, from Romania. Mr. Finn Grav from Norway and Mr. Angel Lopez from Spain have established and chaired the Working Group before for many years.

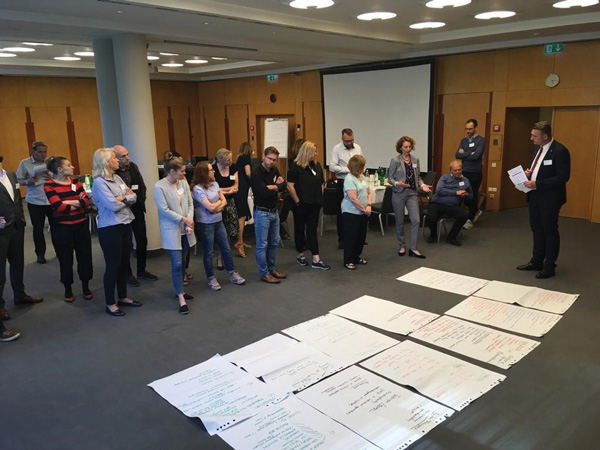

discuss the rehabilitation of radicalised or extremist offenders and review the methods used

in both fields of exit and probation © RAN Centre of Excellence

JT: What are the RAN P&P’s main objectives and top priorities?

TA: The main aim of every RAN event is that practitioners pick up valuable knowledge. The acknowledgement that prison and probation play a significant role in the Rule of Law is important.

The challenges for prison and probation practitioners working with violent extremist terrorist offenders are still increasing and shifting.

As rising numbers of individuals are being held in prison for terrorism-related offences, there is a growing need to respond appropriately to their risks and needs, and to use available resources to prepare them for safe release into society.

For the moment, there is still sparse empirical scrutiny of the underlying social and psychological dynamics behind prisoner radicalisation.

This year, our Working Group will focus on the following issues:

Rehabilitation of violent extremist and terrorist offenders (VETOs). A manual will outline current challenges and practice in organising this process, from a security perspective as well as a reintegration perspective.

Risk assessment. After concentrating on the implementation of risk assessment in 2018, the focus is now on using risk assessment at the individual level and on how assessors are dealing with challenges at the case level.

Prison regimes. A more in-depth account of the experiences of several prison regimes will be developed. The aim is to move beyond the pros and cons of concentration and dispersal regimes and develop context-based lessons drawn from the experiences of a group of EU Member States.

Reviewing exit programmes. Together with the RAN Exit working group, a review format will be designed to help promote the quality and effectiveness of exit programmes.

In general, it is important for us that participants are enabled to make practical use of what they have learned in the framework of RAN events.

JT: What does the WG work consist of, what have you been developing?

TA: It is accepted that prisons are a part of our society. But neither prison administrations nor probation agencies can replace society’s role. Considering the time available in prisons to implement offender rehabilitation and disengagement programmes, it is impossible to guarantee that recidivism is not a possibility. Indeed, the risks of radicalisation are reduced in professional and secure prisons with fair treatment of prisoners.

The absence of these elements can reinforce extremist mindsets and heighten distrust towards authorities, increasing the possibility of groups’ formation and triggers for violence.

Investing in day-to-day staff-offender relationships through staff empowerment, professionalism, respect and dynamic security measures is key to dealing with violent extremist offenders.

This is also one important topic where practitioners can learn from other country experiences.

However, the rehabilitation of offenders must succeed in society ultimately, not only in artificial environments like prisons. Prison and probation services are responsible for preparing and supporting offenders with a view to eventual release, but social inclusion can only occur outside the institution to staging a successful disengagement intervention.

RAN plays an important role in bringing several stakeholders together who play a role in the rehabilitation process in custody and in the reintegration process during the transition period from custody into liberty and after release.

Now, we very much look forward to seeing the upcoming Rehabilitation of Violent Extremist and Terrorist Offenders (VETOs) Manual that will be published most likely in Autumn this year.

Investing in day-to-day staff-offender relationships through staff empowerment, professionalism, respect and dynamic security measures is key to dealing with violent extremist offenders.

JT: What are the group’s most important outputs to date?

TA: The RAN Collection of Approaches and Practices presents a set of several practitioners’ approaches in the field of radicalisation prevention, each of them illustrated by a number of lessons learned and selected practices and projects.

The Collection should be considered as a practical, evolving and growing tool, where practitioners, first liners and policymakers may draw inspiration from, find examples adaptable to their local/specific context and identify counterparts to exchange prevention experiences.

Personally, I find it very useful to have readings available which give insights in adjacent fields of work, which are relevant for my work in the prison sector as well. I can only invite all distinguished readers to visit the RAN website to find all of the valuable resources. As a work in progress, the RAN Collection will continuously be adjusted and enhanced with new practices from EU/EEA Member States.

JT: What kind of previous experience do you have in the area of radicalisation and to what extent does it support your leadership role in the RAN P&P Working Group?

TA: First, I would like to mention that I have worked in prison for 20 years. That gives a great deal of credibility when I talk and work with frontline practitioners.

Some people have a self-image as prison and radicalisation experts without solid hands-on experience in prison, which is concerning to me. Some years ago, I wrote my master’s thesis on a comparative analysis on disengagement from violent extremism programmes (in prison) in the Middle East, Europe, and South Asia.

I was privileged to work in several countries, and this gave me a basic understanding of different prison systems and helped me to find a common language for when I meet all the great practitioners in our RAN network. However, I must admit that I am reluctant to call myself a “radicalisation-expert”. I always learn from other practitioners during our RAN events.

//

Torben Adams is Head of Division in Germany’s Federal State of Bremen Ministry of Justice and Constitutional Affairs; among other tasks, he is responsible for CPVE programmes and initiatives, and advanced training for prison and probation officers. He started his career as a prison officer in 1997; his last post in prison was as governor of a juvenile prison. He has work experience in several countries in Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. His main passions are criminal justice reform and prison development.