Article

Pedro Liberado & Vânia Sampaio

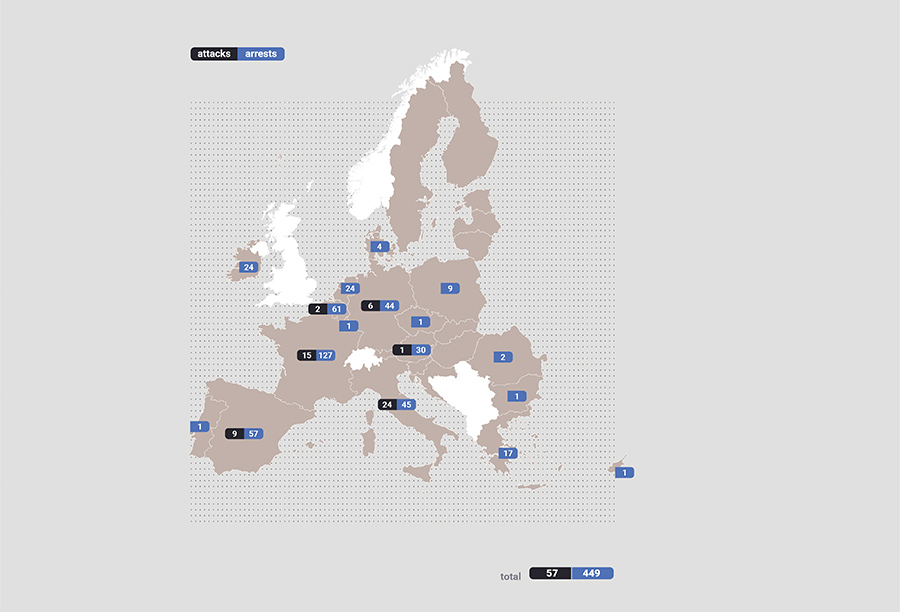

According to EUROPOL (2021), there were 119 completed, failed, and foiled terrorist attacks reported within the European Union (EU) and the United Kingdom (UK) in 2020, which resulted in the killing of 25 people.

Moreover, 634 individuals were arrested under suspicion of terrorism-related offences (EUROPOL, 2021), ending the year with a total of 507 convictions and acquittals for terrorist offences (EUROPOL, 2021; Home Office, 2021).

As some of these offenders had been previously convicted of terrorism or other crimes (EUROPOL, 2021), the need for comprehensive disengagement and reintegration efforts, following a thorough risk assessment process, is stressed. This concern was already emphasised in a previous report; EUROPOL (2020, p. 13) warned about the serious security threat represented by “individuals prone to criminal activities, including those currently imprisoned, who radicalise to violence and engage in terrorism”.

The use of specific-oriented risk assessment instruments

Unsurprisingly, VETOs’ risk assessment within penitentiary settings has emerged as a particularly critical issue within the counter-terrorism architecture (Silke, 2014), especially in the EU (Fernandez & Lasala, 2021).

Although several risk assessment instruments have been developed in recent years (Radicalisation Awareness Network [RAN], 2019), there is a clear tendency to address some concepts in their broader sense, including ‘ideology’, ‘radicalisation’, ‘extremism’, and ‘terrorism’. In most instruments, the discussion of processes and pathways to radicalisation focusses on the same dynamics and risk factors, regardless of the relevant ideology (Khalil, Horgan, & Zeuthen, 2019; McCauley & Moskalenko, 2017).

However, RAN (Ranstorp, 2019; Sterkenberg, 2019) shows that Islamist and far-right extremism are marked by different narratives, ideologies, symbols, vocabulary, and recruitment places. Therefore, although several push/pull factors (including protective elements) are, in a wider frame, transversally concomitant to various radical/extremist ideologies, these should be explored (and adapted) in greater detail. This would mean an increasing compliance to inherent characteristics related to each type of extremism (e.g., Hardy, 2018; Klausen et al. 2020; Skleparis & Knudsen, 2020) and bearing in mind risk variations due to the gender dimension (e.g., Brown, 2019; Jacobsen, 2017; Pearson & Winterbotham, 2018).

In particular, the three risk assessment instruments (i.e., VERA 2R, ERG 22+, RRAP Toolset) analysed in-depth by RAN (Cornwall & Molenkamp, 2018) lacked unique dimensions/indicators related to ideology and gender.

Additionally, radicalisation risk assessment instruments tend to focus solely on VETOs’ evaluation, therefore neglecting offenders who might be vulnerable to/at risk of a cognitive increment of a radical viewpoint. Thus, to broaden the assessment scope into the prevention sphere, procedures should also encompass the identification of (and vulnerability to) radicalisation risk factors within the general offender population (such as the IRS Individual Radicalisation Screening, which is a part of the previously mentioned RRAP Toolset).

Mixed-method and cross-sectoral immersive training approach

The use of virtual-reality (VR) technology in the criminal justice system (CJS) has been gathering growing support, particularly in risk assessment. Cornet and Van Gelder (2020) affirm that VR can help improve the predictive validity of risk assessment instruments by, firstly, offering the possibility to observe behaviour in simulated environments. This is crucial, as de-Juan-Ripoll et al. (2018) state, because the first-person experience leads to more realistic behaviour.

Secondly, it can expose offenders to situations that elicit behaviour without risking the safety of others (Cornet & Van Gelder, 2020). This technology allows real-life scenarios in which frontline and technical staff directly face situations that call for decision-making. The benefits include improved learning results and better assessment of the behaviour of those involved.

Given that the assessment process requires data collection, namely through interviews with inmates and professionals, it is essential that staff acquire competencies that foster the use of developed instruments for these to be effective. Thus, VR-based learning techniques together with e-Learning training would be an innovative way of training different professionals in the field of risk assessment. Ultimately, this training approach will contribute to the successful rehabilitation of VETOs.

The critical importance of assessing and selecting non-institutional actors

It is by now unimaginable to successfully promote a reintegration programme without the support of civil society, as its critical role is widely recognised.

By analysing volunteers’ work in prison, research (Matt, 2015) emphasises the closeness of the volunteer-inmate relationship inside the CJS (whose final goal is to promote offenders’ successful rehabilitation). Nevertheless, external actors’ collaboration with the CJS should be carefully regulated, as it leads to “volunteering in criminal justice (being) increasingly constructed as a hazard that needs to be carefully managed with risk assessment and safeguarding regulations” (Corcoran & Grotz 2015, p. 95).

Although such non-institutional actors have been provided with training, there has not been particular interest in understanding how they are selected and screened, nor in setting criteria for this process. Even though the “basis of good practice is a multi-method selection process” (Aproximar, 2016, p. 21), organisations do not pay due attention to the selection of volunteers, having a relatively simple and insufficient procedure (Aproximar, 2016). Considering that volunteering has become a cornerstone of CJS’s work, the screening exercise is of utmost importance due to the key role of these actors in the disengagement and deradicalisation processes.

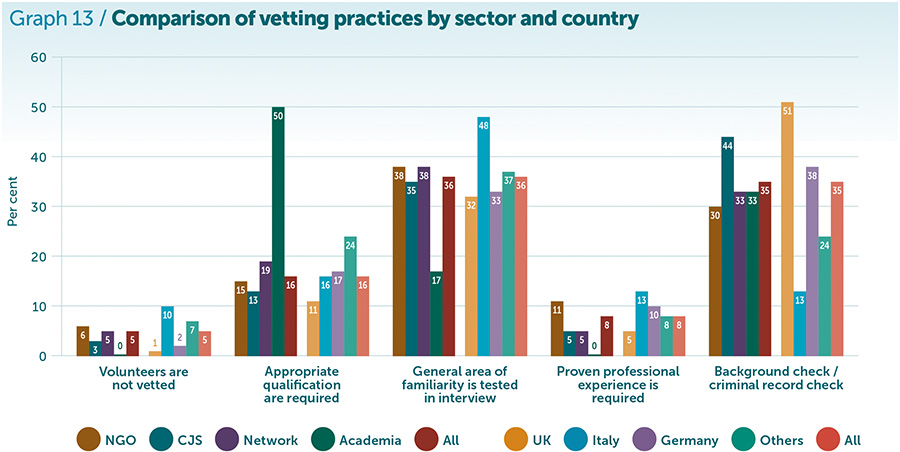

In addition, regarding the vetting process of volunteers contacting with the CJS (as illustrated in Figure 2) and, more particularly, offenders and ex-offenders, it is understood that: 38% of respondents reported checking the volunteer’s familiarity with the area; 37% stated carrying a formal background or criminal record check; 16% reported checking for appropriate qualification; 9% reported checking if volunteers have any professional experience; and 5% reported not having a vetting system in place (Matt, 2015).

Thus, it is necessary to set up a comprehensive selection process of non-institutional actors, entailing a thorough screening and assessment vetting criteria towards their recruitment and final selection (to work in close connection with the CJS). This need assumes even greater importance when dealing with inmates who are/were radicalised or are vulnerable/at risk of radicalisation (e.g., NGO staff members working in disengagement or deradicalisation initiatives and programmes). The criterion should be homogenous across countries and programmes in order to establish a coherent and rigorous framework.

The importance of collaboration between stakeholders

Although the relevance of multi-agency work in P/CVE initiatives has been recognised, it is also acknowledged to be “less well-established” than when dealing with other violent crimes (Sarma, 2019, p. 3).

Indeed, RAN (2019) identified barriers to information-sharing across agencies, namely confidentiality issues and cultures of secrecy. Such obstacles pose significant challenges to multi-agency work in the field of exit work (i.e., work focused on deradicalisation or disengagement). Nonetheless, this collaboration is crucial and should include various organisations, such as law enforcement agencies, prison and probation services, social and health services, youth workers and other civil society groups.

Non-institutional partners, such as non-governmental agencies, are critical to guaranteeing the prison-exit continuum as key exit work practitioners and their roles can go from assessing the needs of radicalised offenders and those vulnerable to radicalisation, to supporting their reintegration into society (Walkenshorst et al., 2019).

MIRAD: A new (and innovative) European initiative built on best practices

In this context, the European Commission, through its DG for Migration and Home Affairs (Internal Security Fund – Police) funded the MIRAD project.

MIRAD, which stands for “Multi-Ideological Radicalisation Assessment towards Disengagement”, aims to achieve a longitudinal implementation of risk assessment tools by building upon the Individual Radicalisation Screening (IRS)2.

Consequently, MIRAD intends to enhance proficiency in the application and management of specific and tailor-made radicalisation risk assessment tools, according to the ideology in question, among prison and probation staff and NGOs working closely with prison and probation services.

Taking into consideration NGOs/CSOs’ (working closely with the CJS) trustworthiness and credibility concerns, MIRAD also strives to expand the collaboration in the field of disengagement between governmental bodies and non-institutional organisations through capability and appropriateness assessments of the latter.

MIRAD will therefore foster the implementation of EU Directive 2016/680 (and beyond), thus receiving heightened attention from key sectoral decision-makers on cooperative relations among prison and probation administrations, judicial practitioners, as well as NGOs.

In short, MIRAD intends to sustainably influence not only the intellectual and policy debate but also the practical application of radicalisation risk assessment tools in prison and probation settings, with the support of NGOs involved within the CJS.

The MIRAD partnership joins public and private organisations that have been selected because of their expertise in the areas of Justice, penological and counter-terrorism research, education and training. It comprises research institutions, NGOs, private companies, and sectoral associations. There are seven EU Member States in the MIRAD project consortium that geographically represent Western (France3,4, Belgium5), Central (Poland6), Southern (Portugal7, Spain8, Greece9), and Eastern (Bulgaria10) Europe.

1Dresden, Germany; Reading, UK; London, UK; Liège, Belgium; Vienna, Austria.

2The IRS was selected by European Commission’s RAN as one of the 14 best practices in Europe (out of 226 reviewed initiatives).

3 Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers

5 International Association for Correctional and Forensic Psychology – IACFP Europe

6 Polish Platform for Homeland Security

7 IPS_Innovative Prison Systems

8 FUNDEA Euro-Arab Foundation for Higher Studies

References

Aproximar. (2016). Good Practice Guide: Recruitment, training and support of volunteers working in the Criminal Justice Systems. JIVE Project.

Brown, K. (2019). Gender, governance, and countering violent extremism (CVE) in the UK. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice

Corcoran, M., & Grotz, J. (2015). Deconstructing the panacea of volunteering in criminal justice. In A. Hucklesby & M. Corcoran (Eds.), Voluntary sector and criminal justice (pp. 93-116). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cornet, L., & Van Gelder, J. (2020). Virtual reality: a use case for criminal justice practice. Psychology, Crime & Law, 26(7), 631-647

Cornwall, S., & Molenkamp, M. (2018). Developing, implementing and using risk assessment for violent extremist and terrorist offenders (RAN EX POST PAPER).

de-Juan-Ripoll, C., Soler-Domínguez, J., Guixeres, J., Contero, M., Álvarez Gutiérrez, N., & Alcañiz, M. (2018). Virtual reality as a new approach for risk taking assessment. Frontiers in psychology, 9.

EUROPOL (2020). European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend report. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

EUROPOL (2021). European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend report. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

Fernandez, C, & de Lasala, F. (2021). Risk assessment in prison. Radicalisation Awareness Network (RAN).

Hardy, K. (2018). Comparing theories of radicalisation with countering violent extremism policy. Journal for Deradicalization, (15), 76-110.

Home Office (2021, March). Operation of police powers under the Terrorism Act 2000 and subsequent legislation: Arrests, outcomes, and stop and search Great Britain, year ending December 2020. GOV.UK.

Jacobsen, A. (2017). Pushes and pulls of radicalisation into violent Islamist extremism and prevention measures targeting these: Comparing men and women. [Master’s thesis, University of Malmö].

Khalil, J., Horgan, J., & Zeuthen, M. (2019). The Attitudes-Behaviors Corrective (ABC) model of violent extremism. Terrorism and Political Violence.

Klausen, J., Libretti, R., Hung, B. W., & Jayasumana, A. P. (2020). Radicalization trajectories: An evidence-based computational approach to dynamic risk assessment of “homegrown” Jihadists. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 43(7), 588-615.

Matt, E. (2015). The role and value of volunteers in the Criminal Justice System. A European study. JIVE Project.

McCauley, C., & Moskalenko, S. (2017). Understanding political radicalization: The two-pyramids model. American Psychologist, 72(3), 205–216.

Pearson, E., & Winterbotham, E. (2017). Women, gender and daesh radicalisation: A milieu approach. The RUSI Journal, 162(3), 60-72.

Radicalisation Awareness Network (2019). Preventing Radicalisation to Terrorism and Violent Extremism: Approaches and Practices (RAN Collection).

Ranstorp, M. (2019). Islamist extremism. A Practical Introduction (RAN FACTBOOK).

Sarma, K. M. (2019). Multi-Agency Working and preventing violent extremism: Paper 2 (Position Paper from RAN H&SC).

Silke, A. (2014). Risk assessment of terrorist and extremist prisoners. In A. Silke (Ed.), Prisons, Terrorism and Extremism: Critical Issues in Management, Radicalisation and Reform (pp. 108–121). Routledge.

Skleparis, D., & Augestad Knudsen, R. (2020). Localising ‘radicalisation’: Risk assessment practices in Greece and the United Kingdom. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 22(2), 309-327.

Sterkenburg, N. (2019). Far-right extremism. A Practical Introduction (RAN FACTBOOK).

Walkenhorst, D., Baaken, T., Ruf, M., Leaman, M., Handle, J., & Korn, J. (2019). Rehabilitation Manual. Rehabilitation of radicalised and terrorist offenders for first‑line practitioners (RAN MANUAL).

Pedro Liberado

Pedro Liberado joined IPS_Innovative Prison Systems in 2018. He would start coordinating the Radicalisation, Violent Extremism and Organised Crime Portfolio team in that same year. He was nominated as Chief Research Officer two years later. In addition to those responsibilities, he has been a shareholder and member of the Managing Board since January 1st, 2022. Pedro Liberado has a degree in Sociology from the University of Coimbra and a master’s degree in Criminology from the University of Porto. He currently is a PhD candidate in Criminology at the University of Granada.

Vânia Sampaio

Vânia Sampaio has been a consultant and researcher at IPS since September 2020. She has worked on several Radicalisation, Violent Extremism, and Organised Crime portfolio projects. She holds a degree in Criminology from the University of Porto and a Masters in Terrorism, International Crime and Global Security from Coventry University, UK. Vânia is a member of the RAN YOUNG Platform, a certified trainer, and has completed the 2021 Scholarship for Peace and Security training programme (OSCE).