Interview

Fiorella Salazar Rojas

Minister of Justice and Peace, Costa Rica

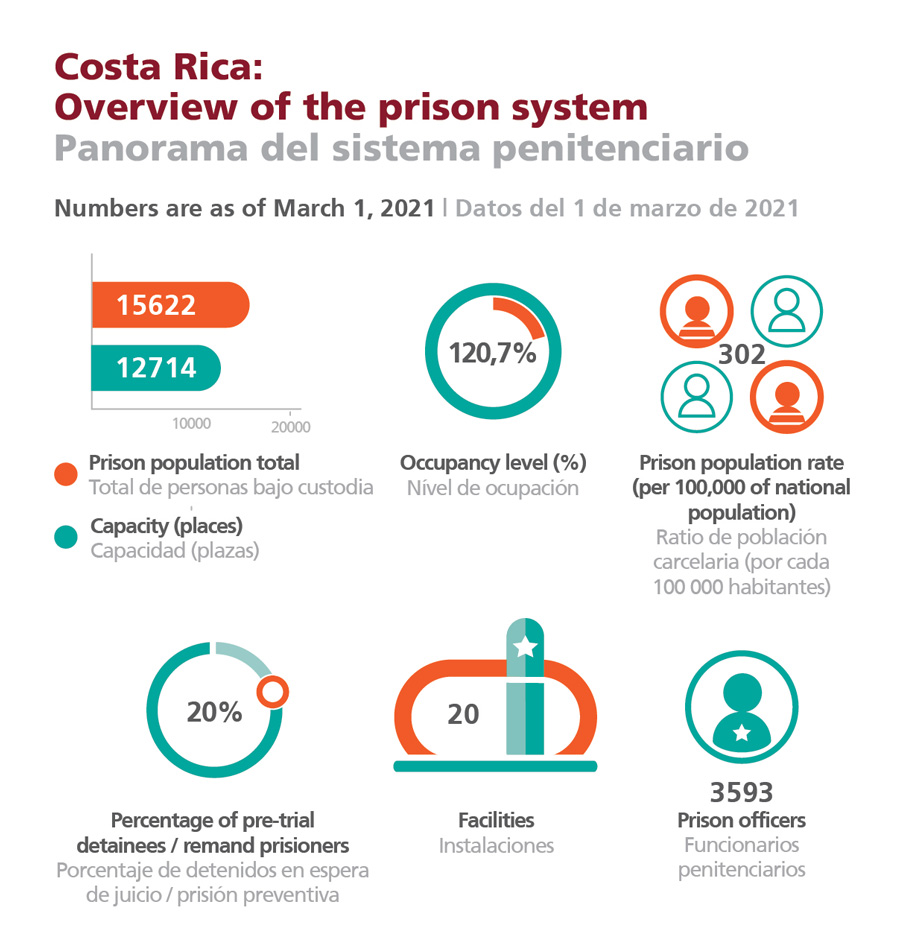

JT: In 2000, Costa Rica had 7550 prisoners and a prison population rate of 193 per 100 000 inhabitants. Over the next 17 years, the number of inmates reached more than 19 thousand, the prison population rate was more than 370/100 000 and the overcrowding rate was at 129%.

What are the main challenges facing the Costa Rican justice system and what are the concrete actions that your Ministry has taken to solve the challenges it faces, namely regarding the penitentiary system?

FSR: We face challenges within the institution, challenges with society itself, and then there are challenges that began with the pandemic, which compelled us to readjust quickly.

Regarding the challenges I see within the institution: on the subject of Peacekeeping (which includes violence prevention and social inclusion), the main challenge is to strengthen the team and find human talent in order to develop a complete range of programmes throughout the country.

On the outside, the challenge is to continue strengthening ties with other State institutions that work with the same target populations, to reach communities and present an attractive offer that adds value to people’s lives through prevention and inclusion programmes. These benefit children, adolescents, women and other vulnerable populations. This was much more challenging during a pandemic because we could not physically interact with people and we resorted to providing virtual services.

On the issue of prevention, the Casas de Justicia (Houses of Justice), where we seek alternative conflict resolutions in communities, closed last year by the pandemic and we had to develop a protocol to provide virtual conflict-resolution services, which this country had never implemented before. About the penitentiary, the challenge is even greater, because we have approximately 15,000 people incarcerated and, last year, the focus was avoiding contagion with the virus, in addition to the challenges that already existed, such as infrastructure and prison programming.

In Costa Rica, each person who enters a prison receives an individualised care plan to follow, which entitles inmates to access job opportunities, for example, either within the prison or through agreements. For us, it is particularly important that people do not stagnate while serving their sentence, but that it be a period of progress.

I would like the prison system to be able to provide people the tools, skills and some type of insight so that when they get out, they do things differently. I would like the prison system to be able to provide people the tools, skills and some type of insight so that when they get out, they do things differently.

If we can get people to change some of their behaviours, we will have achieved something important. Within the penitentiaries, there are people who learn to read and write, who complete their primary and secondary education, and there are people who accrue up to three university degrees. For me, the biggest challenge is not only housing people in dignified conditions, but also providing them with something that also clicks in their lives.

Overcrowding remains a challenge. Currently, we have a prison population rate of 302 per 100,000 inhabitants and the overall overcrowding level is 20%. From 2017 to the present, we have succeeded in lowering the overcrowding rate, but that is overall. We have penitentiaries that have negative rates, but we also have centres that are over 100%, and the great challenge is trying to balance the populations to achieve a standardised 20%, in all centres.

This is a complex issue as the Judiciary makes it difficult for us to view and manage the prison system as an actual ‘system’. In fact, there are more than a few court orders that prevent some centres from receiving new prisoners. The judges, each within their own jurisdictions, only manage the centre under their jurisdiction, issuing court orders on that particular centre without looking at the repercussions it has on others. Some of these orders are years old and have not been lifted even though we are dealing with presiding judges who could review them. So far, only one or two have allowed us to admit new inmates.

Public opinion is an important challenge outside the penitentiaries. Citizens must remember that inmates have had only one right suspended, which is the right to liberty. The work performed by the Ministry is not confined to within its walls alone. Changing public opinion is an everyday task.

JT: In recent years, new prison infrastructures in Costa Rica have received significant investments, including the new Terrazas prison, which is the largest prison investment in decades.

To what extent do the new infrastructures mitigate the challenges facing the prison system in terms of decent space and conditions? What is the role of the external cooperation entities and how they are important in improving Costa Rica’s prison system?

FSR: In two years of administration, we have built around 2400 new prison spaces. Terrazas has been the largest project in decades: 24 million dollars have been invested, 17000m2 and more than 70 buildings constructed in order to house some 2250 inmates.

At the same time, we have implemented small projects that added some spaces. For example, we have a regionalisation project in which we are creating 36 penitentiary spaces for women in different parts of the country, in order to address the issue of entrenchment and allow women be located in their areas of origin. In many cases, they are mothers and heads of households who are far away from their children.

These spaces also have nursery rooms because many have their babies inside prison – in Costa Rica children can remain with their mothers until they are 3 years-old. Additionally, we have created 56 spaces in existing prison facilities, and devoted more than one hundred spaces to therapeutic rehabilitation, in collaboration with the University of Costa Rica. These are for young people undergoing substance abuse rehabilitation.

Although part of the infrastructure is not yet in use, it is in a period of retooling and we are handling management to provide staff, mainly prison police officers – with tacit approval by the Treasury before it goes to Congress. Therefore, it becomes a process beyond the provision of infrastructure alone.

Regarding prison matters, we had a particularly important collaboration with the IADB, from 2012 to 2018, where, due to a $67 million loan, we built three Comprehensive Care Units. These have a different infrastructure relative to other penitentiaries in the country. The endeavour aims to recreate life on the outside, where people move about a little more freely; they can walk throughout the unit, use the sports facilities, industrial workshops, and there is an educational element, etc.

Moreover, it is not only infrastructure, but also a whole model created, including a profile of those who could benefit from this type of centre, where the work with the inmates is different from other penitentiaries and there are more options for social reintegration.

Regarding multilateral organisations, this was the latest and the largest. We built the Terrazas centre with our own resources, without obtaining any other loans. However, we are currently in talks with other multilateral organisations, although we have not yet reached any specific agreement.

JT: In August 2018, the Costa Rican President signed the law to block cell phone signals in prisons (1). In October 2020, a declaration stated that cell phone signal blocking was going into effect, but it still did not cover all correctional facilities on that date (2).

What impact is this project expected to have? And, to what extent does the slow implementation of some projects prevent the Justice system from attaining better results?

FSR: The expected result of the signal-blocking project is to decrease – hopefully eliminate, but we know they are difficult to eliminate – telephone scams of which Costa Rican society is a victim in general. It was determined that many of these scams came from cell phones in the penitentiaries.

Therefore, the law took effect in 2019 and we had a period of nine months to implement the technological solution, that is, until April of last year.

Because of the pandemic, we had delays due to technical difficulties, but in October 2020, most of the penitentiaries in the country had already applied the technological solution and implementation would be complete by the end of the year, which is what happened. Moreover, beginning in January and throughout this year (as of March 11, 2021), the necessary calibrations are being implemented, particular cases have been identified and the providers are complying with the signal blocking in the centres.

The law that provides this project’s framework established two mandates for telephone providers; on one end, mobile phones cannot function inside the centres. Simultaneously, the service must not affect areas surrounding the centres. Nonetheless, this is the immense challenge that providers have faced in recent months, since they may very well block signals within the centre, but they are receiving plenty of complaints from those who live nearby or from people who enter a centre to render services, then upon leaving the centre their phone does not work for a couple of hours or more.

It was the obligation of the Ministry to facilitate the implementation of the project within the centres. According to the latest data I have, we have already had more than 5000 blockages performed within the penitentiaries.

In reference to the duration of project implementation, when it is only inside the institution, I think it is simpler because it is a matter of explaining and pushing things forward. The Ministry has achieved many things internally over these last few months and with this administration. Sometimes projects take longer when we must interact with other institutions, for example, when we need permission from Congress, however, we are still achieving a great deal.

Very recently, we signed a joint work protocol with the Mixed Institute for Social Assistance, which works with vulnerable populations throughout the country. With this protocol, we are exchanging people between both institutions. Another example was the approval of funding from the special budget for Ministry projects in the Legislative Assembly: it only took us a matter of weeks, because there was especially good communication. It is a team effort!

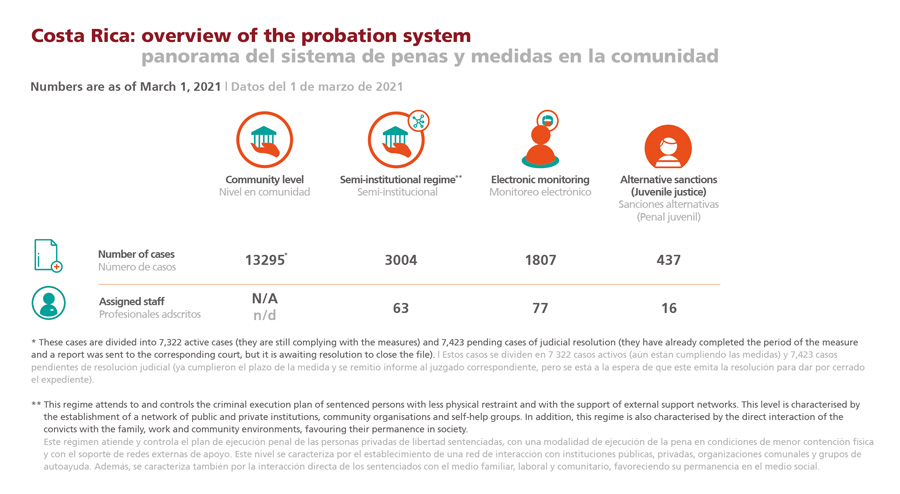

What is the state of affairs regarding community measures and sanctions, and electronic monitoring in particular?

FSR: We have, at this moment, 14,250 people in alternative measures and about 1825 under electronic monitoring (they are two different groups). To deal with the issue of alternative measures, we have created Community Care Offices, which follow-up very closely, on the ground. The electronic monitoring law passed in 2014 and this system is at a mature stage. Last year we incorporated new technical and police personnel.

The people who are under electronic monitoring have professionals working in education, counselling, law, psychology and social work to support them and, in the same way as prison inmates, those monitored comply with an individualised care plan which includes education or work.

Additionally, last year we implemented a technological improvement. This new tool allows us to send information to the presiding judge in real time, for example, whereas before there might have a lag time of several months. Moreover, in mid-February 2021, we placed a bid for tender as the new supplier for the next four years. According to our calendar, by the end of this year we should be signing the new contract. I really feel very hopeful that current progress and the next stage will bring about greater consolidation.

JT: The COVID-19 pandemic has brought great challenges to prison organisations.

Given the restrictions resulting from the pandemic crisis, what kind of measures have been implemented in Costa Rica?

FSR: In the prison system, we started preparing before the virus arrived in Costa Rica – the first case of infection in the country was on March 6, 2020 and in a prison, it was on July 1, 2020. From February, we started working as a team with the Ministry of Health and the Costa Rican Social Security Fund, which manages the public health services network in the country.

We immediately set up a protocol to work inside the penitentiaries – at the beginning it was a lot of hand washing, respiratory etiquette, and social distancing – but this protocol was revised and adjusted (we are already in version 7) as the health authorities have further advised us.

We have had a year of difficulties. Today (March 11, 2021), we have only 17 positive cases in the entire prison system. The strategy that we have used from the beginning, beyond hand washing and all those protocols, was isolation. In each penitentiary centre, we identified spaces that were to be exclusively reserved for isolation, to isolate both people who tested positive and those suspected to have been in contact with the virus, such that each person who comes from a jail cell has to undergo a 14-day isolation.

Some people arrived in the prison system having already tested positive for COVID-19, and then complied with quarantine until they recovered and the health order was lifted.

In addition, anyone inside a prison who went to a doctor’s appointment or court appearance, upon return, also had to go into isolation. I believe that this “firewall” was what prevented us from having a massive outbreak in the penitentiaries.

Fourteen inmates have died of COVID-19. All received care like any other citizen in the social security system. We also had infected personnel and they have recovered. At this time, the recovery rate among inmates is 165 to one active case; 99% of people who have had the virus have recovered. Before the pandemic arrived, we built great awareness within the prison population through many discussion sessions.

The inmates committed themselves to prevention to such an extent that they asked their families not to visit them.

In fact, on March 20, 2020, we had to suspend visits, which did not resume until December 18, 2020 – I am very proud to say that we have not had a single infection due to a visit.

Contact between inmates and their families was very limited. In August, we initiated virtual visits in the women’s prison, after which we moved on to juvenile corrections.

However, in the bulk of the prison system, which is comprised of adult men, it was more complicated because we had neither equipment for virtual visits, nor the expertise to organise them, so that everyone could conduct their visit at a certain time.

However, through equipment donations, we were able to implement virtual hearings so that inmates could participate in their judicial cases without having to leave the centre. This led to very close coordination with the judiciary throughout the country.

At this time, visits are very controlled: only people of legal age can enter, only one person per visit, there is a one hour time limit and they have to adhere strictly to the protocols. Once the visit is over, the people who have had visitors must clean the space, wash the clothes they were wearing, and bathe.

At this moment, we are following the vaccination groups that the country has defined for the entire population. Within the penitentiaries, we have started vaccinating health personnel, we have already vaccinated a large percentage of prison police officers (Prison Police) and 100% of our prison facility for the elderly.

The pandemic was a big challenge, but we have been doing a wonderful job. We even made a documentary, over these many months, on how the issue of the pandemic has been evolving in the prison system.

(1) Jiménez B., E. (2018, August 16). President signs law to block cell phone signal in prisons (...). La Nación.

(2) Ministry of Justice and Peace (2020, October 23). The wait is over: cell phone signal jamming comes into operation in the Costa Rican prison system.

Fiorella Salazar Rojas

Minister of Justice and Peace, Costa Rica

Fiorella Salazar Rojas has a degree in Economics and a master’s degree in Project Management. She has extensive training and professional experience in project management, leadership development and results orientation. She held various consulting and coordination positions during the years she worked at the Inter-American Development Bank from 2009-2018. At the same time, she was a university professor in the field of project management. Upon assuming office for the Ministry of Justice and Peace in February 2020, she was Deputy Minister of Public Security.