// Interview: Fabiano Bordignon

General Director of the National Penitentiary Department (DEPEN) Brazil *

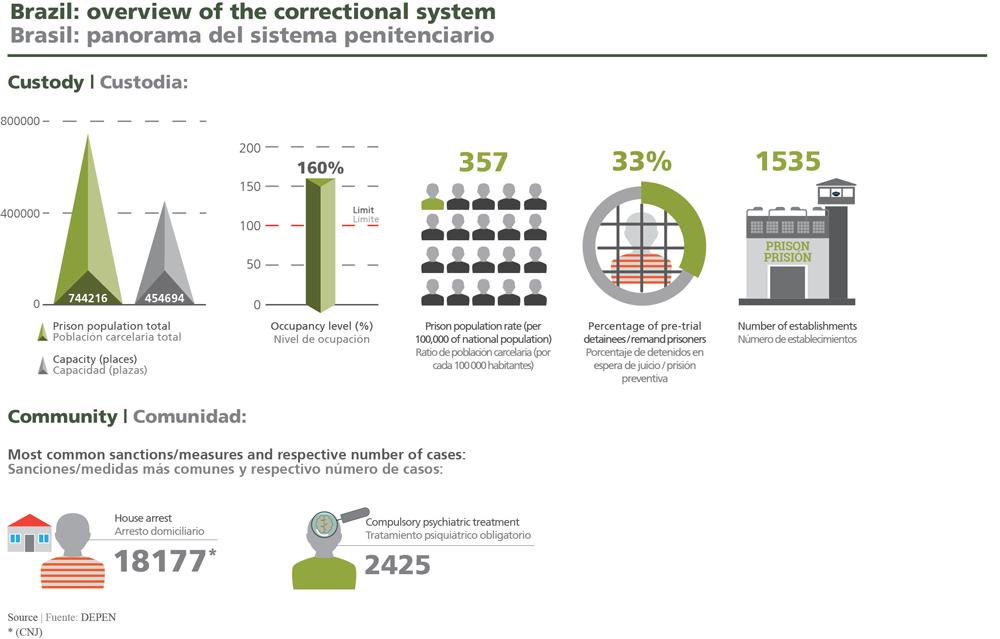

JT: The population of Brazil increased by more than 400% between the end of the 90s and the present day, going from less than 200,000 prisoners to the current number which, according to Sources from the National Council of Justice (CNJ), exceeds 812,000. What exactly has DEPEN’s function and scope of action been in Brazil, and how can DEPEN support penitentiary reform at the federal and state levels?

FB: The National Penitentiary Department (DEPEN) is linked to the Ministry of Justice and supports states in technical matters of prison management. We also manage the national penitentiary fund, which is a public fund directed towards penitentiary investments. This fund is capitalised with resources from criminal fines, lottery games, among others. In this context, DEPEN manages and systematically distributes to all units of the Federation. DEPEN does not directly manage state units. Brazil is a Federation which has 26 states that have their own penitentiary systems. DEPEN seeks to unify and induce some policies, to help states, and to be a fostering agency to improve the prison system.

DEPEN also acts in moments of penitentiary crisis. We still have a lot of problems with the control of the prison units. Brazil was left for a long time without investing in prison units in a systematic manner and this led some criminals to unite and create factions. Brazil’s main criminal factions are born inside prisons. We also work on the restoration of control of these more chaotic units in coordination with the Federation units. Whenever a crisis occurs, for example in 2019 in the state of Amazonas, DEPEN brings together prison agents in several states to help the state in question overcome the crisis. DEPEN also helps to aggregate cooperation among all federative entities to overcome penitentiary crises, arising from a historical problem of a lack of policies to improve the quality of the prison service in Brazil.

JT: But do you also have a federal prison management system?

FB: Yes. DEPEN directly manages 5 federal prisons where the main criminal leaders of all states are sent. We have a small, qualitative system. Only the inmate with a negative leader profile goes to federal prisons. There are some similarities, for example, with the Italian prison. This system has helped to diminish the influence of criminal organizations in state prisons, but it is a process that will take some years to improve, as will the control situation in Brazilian prison units.

Brazil was left for a long time without investing in prison units in a systematic manner and this led some criminals to unite and create factions. Brazil's main criminal factions are born inside prisons.

JT: The Ministry of Justice and Public Security has outlined a set of strategic actions to face justice system challenges and improve levels of public security. What are the projects in which the prison system is involved, and which are directly targeted within this strategy?

FB: One of the main projects is trying to maximise vacancies. We have several actions, and one of them is to increase the penitentiary works. To have more prison units, the goal of the national penitentiary department is, in coordination with states and federal agents, to create 100,000 vacancies in 4 years. Opening vacancies doesn’t just mean building prison units. We need to be and are investing in electronic monitoring. Today, Brazil has over 50,000 people who use electronic anklets. It is an alternative to imprisonment, both for precautionary sentences and for the semi-open regime.

In some cases, the inmate wears the anklet and goes to sleep in his own home. This avoids the need for greater investments in prison units. Another project we are working on has to do with the creation of a unique data logging system. Brazil does not yet have a single system with all the data of the prisoners. The first version should be ready by December 2019. Each state has its own prison relationship, but there’s no single system. DEPEN has the data for 2018 with 750,000 prisoners in the three regimes – closed, semi-open and open. It differs somewhat from the CNJ data because there is a verification period and, in some cases, it does not involve the prisoners who are in police stations. It’s an average of 700,000 to 800,000 prisoners.

We have a vacancy deficit. We also need to involve private initiative in the construction of new prison units through public-private partnerships and co-management with the public and private sectors. There are several actions: opening of vacancies, restoration of control, and the equally important work of penitentiary intelligence.

In 2019, the Minister of Justice authorized the creation of a Penitentiary Intelligence Directorate to work with a focus on the individual inmate in prison. This involved answering the following questions: Who is the inmate? What relationships do they have and what unit are they in? Are they a member of a criminal organization? All this has an impact on prison management.

To have more prison units, the goal of the national penitentiary department is, in coordination with states and federal agents, to create 100,000 vacancies in 4 years.

JT: Some violent incidents with factions in prisons occur frequently. This was the case in gang clashes in Manaus, Amazonas and in Altamira, Pará. It resulted in the deaths of several dozen prisoners in May and July 2019, respectively. What kind of intervention does DEPEN have in the management of these crises, like those that occurred in Manaus and Altamira?

FB: These are one-off crises. We have over 1,500 correctional facilities. What happened in 2019 were disputes between the factions themselves. Brazil is a country that has a lot of drug flow in its continent because it is close to producing countries. During these crises, DEPEN forms teams that we call the penitentiary cooperation force. Each state yields experts, its best agents. This team cooperates with the state to put order into these prisons that have been out of control for a long time. We have had occasional crises in some establishments. We had a crisis that involved four prisons in Amazonas and another that involved a prison unit in Pará. We are still working in those two states. In early 2019 there was also an intervention in Ceará, but it was not a rebellion within the units. Organized crime tried to use terrorism in the streets, and this was overcome.

JT: You advocate the expansion of the APAC method, recovery centres managed by an organization of religious origin, which house between 80 and 240 individuals deprived of their liberty, which are called “recuperandos” (recoveries) and where there is no armed surveillance. What advantages do you see in these detention centres and how can the expansion of this type of partnership help government projects in the prison area?

FB: DEPEN has promoted some meetings with protection organisations and assistance to convicts (APACs) and we will reserve resources to help finance works for new APACs units in 2020. APAC allows a very strong movement of the local community in the management of the prison unit. They are small units with a lot of moral and religious discipline, with values such as respect and family. This is a revolutionary method that began in Brazil in the 1970s, and the Federation of APAC associations has already disseminated this model to some countries in the world. There is a notion that there are only crises in the penitentiary system in Brazil. On the contrary, there are a few one-off crises, but there are also improvements. APACs are a path in that direction. We are in coordination with the states to try to expand the APAC system. This depends very much on the collaboration of the cities, the population in the unit, and the judge himself. We want to increase this involvement and in 2019 we carried out some meetings and studies. In 2020 we intend to make an investment to support this method that we consider important.

JT: You spoke of the importance of having information and making a strategic analysis of the entire penitentiary system in Brazil. One of the big problems has to do with a lack of data and indicators. Is anything being done to get a more accurate picture of the system?

FB: Yes, we will publish a ranking probably in the month of January 2020, with a grade for all prison units in Brazil: “level A, B, C, and D”, for all of the over 1,500 Brazilian prison units. “Level A” corresponds to the prison units that comply excellently with all the items foreseen in the Brazilian law of penal execution. However, very few units are “level A”, but very few are “level D” as well. Brazil has a level of penal execution with many “level B” units and some with “level C”. The challenge is for each prison unit to be reviewed in the ranking, and for there to be an effort and commitment from the state manager, the judge, the public ministry, and society itself to raise the level of each prison unit. The improvement of prison units leads to the improvement of public security.

There are several structural changes that will take some time, but the idea of having a ranking that will have a healthy competition effect between units throughout the country makes it worthwhile. We can thus see which is the best unit, which is the worst, which ones can improve, and in which aspects: security, inmate assistance, health, education, legal assistance.

In 2019, the Minister of Justice authorized the creation of a Penitentiary Intelligence Directorate to work with a focus on the individual inmate in prison.

JT: There has been great interest from several states in moving towards public-private partnerships (PPPs) in prison construction and operation. What is DEPEN’s role in this process?

FB: DEPEN is bringing together several “experts” so that states that want to move forward make the best possible decision and create several models instead of a single model. As Brazil is very large, some solutions apply in some regions, but not in others. PPPs are important to help the Brazilian government face the investment deficit in the prison area. We rely on private partnerships, but models have to be built. There are several models worldwide, but we can create a Brazilian model. Today we have few units with PPP. There is space within the goal of creating 100,000 vacancies so that most of them are made by establishments built by private initiative.

//

Fabiano Bordignon is the General Director of the National Penitentiary Department (Depen), graduated in Law from the Pontifical Catholic University of Paraná. Post-graduate in Criminal Law and Criminology at the Institute of Criminology and Criminal Policy of Paraná. Post-graduate in Political Science, Strategy and Planning with emphasis on Borders. Master’s in Society, Culture and Borders from the State University of Western Paraná. Deputy of the Federal Police since 2002. He started his career in Porto Velho/ RO. Director of the Federal Penitentiary in Catanduvas/PR (2009-2010 and 2012-2013). President of the Council of the Federal Penitentiary Community in Catanduvas (2014-2018). Head of the Federal Police Station in Foz do Iguaçu (2015- 2018), Coordinator of the Tripartite Command Brazil since 2015.

* Mr Bourdignon withdrew from the position of General Director of the National Penitentiary Department (DEPEN) in late April 2020 and does no longer hold the post held at the moment when this interview was done.